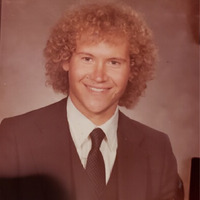

Ross Hudson's Oral History

Ross Hudson was born in 1956 in Florence, Alabama to a Jewish mother and non-Jewish father, which shaped his overall worldview and perspectives on diversity. He is currently retired and lives in Scottsboro, Alabama with his partner, however he previously had a career in the public health field, specifically in social work. He earned his undergraduate degree in social work from the University of North Alabama, and then came to the University of Alabama for graduate school. At UA, he was one of the founding members of the Gay Student Union, that worked to provide safety and community for LGBTQ+ students, especially during the HIV/AIDs crisis. After helping found the GSU at Alabama, he was kicked out of the university due to their prejudice against the LGBTQ+ community, which led to his enrollment at the University of Georgia, where he helped found the GSU there.

Hear Their Story

See The Transcript

Interviewee: Ross Hudson

Interviewer: Bryce Schottelkotte, Indi Robinson, Ashlyn Hinds

Date: November 17, 2023

This is an oral history interview with Ross Hudson. It is being conducted on November 17, 2023, at the Tuscaloosa Public Library and concerns his experiences being openly gay in the South in the 1980s, as well as his work as one of the founding members of the Gay Student Union (currently Queer Student Association) at the University of Alabama and University of Georgia campuses. The interviewers are Bryce Schottelkotte, Indi Robinson, and Ashlyn Hinds.

RH: And if they found you in bed, even if you were just sleeping, you weren't doing anything, they would say, okay, you're gay or homosexual and you need to be arrested. So, you have to keep that in context of how the organization was formed; that everybody there was at risk of being locked up, just from a legal standpoint. It had nothing to do with the university, it was just that if somebody got mad at you, and they didn't like you. And, sometimes you'd have gay people report other gay people if they got mad at their boyfriend or whatever. And they, you would like to say people were not nasty back then, but they were just as nasty as they are now. Anyway, I'll talk a little bit about the whole thing, and then I can go back to y’all’s questions, whatever works for y’all.

IR: All right, go ahead.

RH: Okay. Anyway, I was the treasurer when we first started off. And, people say, well, how did y’all meet, and how did you find each other? And, we kind of joke about gaydar. But back then, we didn't have cell phones, we didn't have computers, there was no Grindr, and there was no way for people to meet up unless you actually talked to somebody or were around people. And so, like on campus, I lived in the dorm. It's torn down now. It used to be Sanford, or Samford, right there by the Ferguson, and it didn't have air conditioning, and it’s the first place I'd ever lived without air conditioning. And it was like, okay, I thought when you came to the University of Alabama, you’d at least have air conditioning. And we didn't even have that. But anyway, I knew who was gay or bisexual in the dorm, because you just looked at each other, you knew, you just knew. And it didn’t make a difference if you were male or female, you recognize that, hey, they may be like me. And you wouldn't just automatically come out and say, are you gay? We didn't even use those terms. Really, that was something new.

Because the whole thing when you're talking about southern queer history you have to think about; I was called queer since elementary school. Considering my age and everything, I'm 67. And so, it's not an endearing term to me. I can embrace it in the evolution of our journey, but it's kind of like, if you ask an older black person how they feel about the N-word, that's how I feel about when I hear queer. Because it was never a term of endearment. It was never something that was to be proud of. That context wasn't there. So, it's kind of strange, I guess now, when I hear people identify as queer is kind of, okay. I keep going back to how I felt 40 years ago or 50 years ago, about being called that. So, it wasn't something that feels good to me. But I can embrace it as far as our community, if that makes sense. It was just a different time.

RH: But anyway, so I have all these records. And they, I mean, you have to think, we didn't have computers, you didn't type out anything, you had to handwrite everything, or you had to pay. I had come to the University of Alabama to get my master's in social work. I love social work; I got my undergraduate in social work. I had a double major from the University of North Alabama in history and social work. And so, coming to Alabama was my dream. I had been in the closet all of my life. Even though I always tell people, in first grade, I knew I was different. That I liked playing with the girls just like I liked playing with the boys. And you have to think about back in those 60s period of time, boys, especially young boys, they didn’t want to play with girls. It was just boys wanted to play with boys and girls wanted to play with girls, and so I could play with either and I enjoyed it. I knew I was different, but I didn't know why I was different. I'm Jewish, I grew up in a mixed family. My father's not Jewish, and so we didn't go to regular church like folks. But we had scripture reading at home, and so my whole thing was brought up to you want to change the world, you want to make the world a better place. I always thought it was just part of my Jewish background of you contribute to the world. It’s part of your duty to do that. And I was the perfect little boy, if that makes sense. Everybody, girls wanted to date me, even though I didn't want to date them. I was the perfect brother, the perfect son, I never got in any kind of trouble, I didn't use drugs, never wanted to. I just wanted to make good grades and get along. I enjoyed being with people. Always did. And I kind of grew up, I didn't realize, I thought we were just like everybody else. But I realize we were, now I realize we were upper-middle-class folks. We had a house in town, and we had a 500-acre farm that we had another house on, we’d go out to the farm and live.

You have to understand, everything was segregated back thing. I was in fifth grade before our school was integrated. I still remember the teacher coming in and saying, there’s going to be some changes, and we're going to get a new student, and she's going to be different. But let’s all work, she got real positive thing. I still, remember that student, her name was Vivian Robinson, and her daddy had his doctorate degree, in some type of chemical engineering, or whatever, and had moved there with TVA. You have to think about when I grew up, that's how far back things were. I remember my grandparents, or my grandmother owned, I remember going into Sears and Penny's and there being a separate entrance for blacks. My grandparents owned the black grocery store in Florence and blacks could come in the front door and stuff. So, I'm saying all this, because I’m trying to give you a context of how the world was then. So, you had the race thing going on. My parents, I realized, now my grandfather and father were very liberal because they were always supportive of my grandmother and mother having their own money, their own business. My grandmother was a businesswoman, had the grocery store, and then she bought rental houses and did all that. And she had separate money from my grandfather's. And my mother became a teacher, and different things. But I guess I grew up thinking, I saw women treated equally in the home. So that's how I grew up. And that's how my sister and I grew up. The context of how you had the racial thing going on, you had the male-female thing going on, and you had the gay thing that just wasn’t even spoken about. All of that was going on. But I had, I would say, an uneventful childhood. Besides once you got to puberty, and you seem to realize, other people were talking about kissing girls, or getting first, second base with girls, that kind of stuff, it was kind of like, that's not what I want. But it wasn't, you were so afraid to, you didn't tell anybody, you didn't express those things, because you were afraid that someone would accuse you of that. And that was always the thing of calling somebody, if you didn't like somebody, you’d call them queer. And so, you avoided trying to give any appearance at all of that.

RH: I essentially, I went through all of my undergraduate work was, I didn't, I knew a certain people that were, you would, you would meet people and have sex with them, but you didn't know them. I mean, you didn't get to know them. And you'll be like, you did that, and then you never spoke again. And you would avoid each other. If you happen to run into him, you acted like you didn’t know them. That was just normal. It wasn't rude. It was just everybody's survival if that makes sense. And so, I came to Alabama thinking okay, now away from home, I can do my own thing. I'm coming to social work and social work is supposed to be so liberal and accepting. And then I walked into a situation. You have to think about in the 80s, there was, and I brought some articles and stuff about, people started thinking about gay rights. And you heard about things going on in New York and California. What those queers are doing is what people would phrase it as. And so, you get here and you're thinking, okay, you begin to meet people. And you think, okay, why can't we do that here? And so, several of us, it was just word of mouth. There were no cell phones, there wasn't any. And you knew, and you would get to know people. And you have to think, the black population at the University of Alabama was small at that time. And so, if you, if you had, let's say if you had had sex with someone or whatever, that's how people, sounds awful, I guess, in one way. But people got to know each other, and you included.

And you have to think, I’ve read some of the things about when people were talking about like, why was it called the gay student union? Well, that's how people saw our community as just gay. It didn't make any difference, if you were lesbian, or transgender, or whatever you were, they just saw you as gay. So, it wasn't any way to exclude people or anything like that, it was just that, we were the gay community. And you have to think about the context of when what you do in the privacy of your home is illegal, and you can be arrested, we all stuck together. It was one of those things of where we wanted to make sure that if we had a male Vice President, then we wanted a female President, that kind of stuff. So, it was an equal thing as far as gender. Your officers, you had to have half female, half male, but we're all just considered gay. And , I would say at least a third, quarter to a third of the students were African American. But it was because we all knew each other. And I think that there was an African American male in my dorm, that he and I knew each other really well. So, I invited him to the meeting. And we would meet like at the school social work, just kind of like this, you all just happened to all be somewhere, and we’d just all talk. And then you had to cover up our conversation, and we didn't identify why we were there. It would just be students coming together talking and we just enjoyed being together. And you have to think about that context of we didn't, now everybody's caught up in certain identities and in saying well, I have to be this way or that way or that kind of thing. And back then, you have to think about we were all just labeled gay. It's kind of like the Jews being Jewish, I always think about the concentration camps and stuff. They didn't divide the Jews up okay, you're Polish Jew, you’re French Jew, they divided male, female. But they mixed the rich with the poor with, , it was not. And you have to think, back then, that's how we, we were a community and we supported each other.

And I was telling Isabella that I lived in, I started out at the dorm. And I signed the petition, I was number six on the petition. I guess y’all have seen those petitions, the original. They had the original petition that was presented, and then they had the one that was presented later. And so, the University got really upset. Dr. Thomas was the president at that time; he didn't want a gay organization on campus. People thought we were just there to date each other. It was like, we had already dated each other; we were not interested in that. And we said that we wanted, you had to be over 18 because we didn't want anybody accusing us of bringing kids in to do, . And even though there were young people in this community that identified as being well, queer. But we were as supportive as we could be, but they were not at our meetings or anything like that. Because the whole thing was, we're trying to jump through the hoops to get recognized. And anyway, I just wanted to explain it because sometimes people wonder, well, why did you not do this or do that? It was like, okay, we were all one community. And after I left the dorm and got my own apartment, I lived Reed Street Apartments, and that's right off The Strip. Back then there was nothing here. I mean, I'm always shocked at how much University has grown. But back then it was a nice apartment complex, it actually had a swimming pool back then. And so, we'd have meetings, and there were probably four other guys and there was one girl that had an apartment there. And so, we would have our meetings at Reed Street. And so, especially in the summertime, we would go after the meeting, everybody was just college kids, and we'd all go skinny dip. And so, that was first time I'd actually been skinny dipping with a woman. , people looked out there, they just saw a bunch of naked college kids. They didn't know that we were, it was female with female, and male with male, not people doing each other. Even though we had some bisexuals in the group. We were all really friendly with each other, I guess is my thing. And so, it did away with the sexual tension.

RH: So anyway, I brought these things. And see, I don't know how people feel. These were just some notes I have where they were paying dues and stuff. But anyway, these were the original 35 people that were on the. And see, nobody kept any records because nobody wanted. I kept them because I had to keep up with the dues. And so, I don't know, yeah, these people might have gotten married, had kids are, , I have no idea of what, what's happened. And there's one guy on there, that was actually my partner. He was bisexual and ended up through life becoming essentially gay. But he's on there, and he lives in New Hampshire with his partner now. And we've remained friends all this time. We were together for five years, and then we broke up. But we were business partners, and we've worked with the same mental health center, and that kind of thing. But anyway, these were the people that were there at that time. This is the original Constitution.

BS: That is such a cool logo. I want that on a T-shirt.

RH: And this is one of the articles that came out that we submitted to the Crimson White. This was the, we had a rap group. And so, if somebody wanted us to come talk about gay issues, I keep saying, gay, but it was at that time there, now they’d just say queer. We had a speaking group, in a way we weren’t experts, we were just regular people trying to be supportive of other people in the community. We had this human development section class that we talked with, and we have this rap group. These were some of the notes from the speaker's bureau, some of the things that we wanted to cover. Some of this stuff might be interesting. These are all original newspapers of when. And I don't know if you have seen all these or not.

IR: No. I don't think I have seen these before.

RH: But anyway, this is when we were seeking the, getting the charter. See that started back in February, they didn't approve anything until, I think it was September, October of that year, but we submitted the first names early. And so anyway, these are all the papers and stuff and y'all can see them. There were different things in regard to that. And here's, I don't know if they still do it, but anyway, this is what the Crimson White used to do, like kind of gag papers and stuff. Well anyway, this was the headline. Being fag was the other thing that they called you. , queer and fag. But anyway, that was that. These are all the letters to the editor about not, , saying that we were dying and go into hell, and all that kind of stuff.

IR: So where were you actually born?

RH: I was born in Florence, Alabama

IR: Right

RH: And like I said, I'm 67. I grew up in Florence, lived there all my life. Loved it. If you took out the sexual identity piece of it, I had a good life, it's just that that was part of my life I had to cover up. I never found the perfect girl to marry and everything, and I didn't have any. once I came out, and it came out once I got kicked out of the university, and I had to go The University of Georgia. And y'all can pass, I just thought I'd let you say there were actually things that were supportive and not supportive.

My parents found out that I was gay. And I was disowned. And so, I had to do a variety of things to survive. I was a lifeguard here in Tuscaloosa and taught swimming to the kids. I did that that summer. I also worked at the mental health center as a house parent. I worked for Indian Rivers and did that. Once I finally got, and what it is, I got kicked out of the University at the end of ‘82, in December. But because, I hired a lawyer and got back into the University, because they had not followed all their procedures and I claimed I was being discriminated against, they let me back in. And so, once all that came out, and I ended with the University of Georgia, then I got disowned. And my parents, well mainly my mother, said not to tell my sister. Because my sister and I had always been really close and everything. And so, I honored that and didn't say anything to her.

And so, here on campus I was out. I mean, you didn't rub anything in anybody's face, because you were afraid to get beat up. You'd meet people. And I don't want it to sound all negative and stuff, because there were a lot of people that were just wonderful people. We enjoyed each other's company, we had a lot of laughs. I mean just because you're being persecuted, and you can't have a good time. And so, when we were together, we really enjoyed being together. And there was, I don't even know, it was like a big creek that people would go tubing and that kind of thing. It wasn't the river down here, but it was some out in the country. And we would go tubing on that river, or that big stream and stuff. And so, we’d do fun things like that. And a lot of times we would go to the local bar, back then there were just really, two or three bars at that time, big bars that you could go dance. And so, we would dance with each other. Boys would dance with girls, but you'd be dancing right beside your partner, and they'd be dancing with her partner. I mean, it was all we could do. They had a bar here that was called The Chukker. And it scared me. First time I went, this was before I had a boyfriend, and so I went and looked, pulled up and I knew it was over there. And I saw a guy come out with a baseball bat, and he started beating the windshield out of a person's car. And it scared the crap out of me. And I thought, I don't know about these people because that's not what scared me. And so, after I got a boyfriend, then it was like okay, well, let's go. And so, then we went, and we enjoyed it. But I don't know what would have happened before in that situation. But it was scary. The guy I was dating at the time was from Montgomery, and they had a bar down there called Hoe John’s. And so, when we’d go to Montgomery, we went down to Hoe John's, and it was a really nice bar. Really in a nice building and everything.

BS: So just make sure that we get to the questions, sorry.

RH: Okay.

BS: We already answered, honestly, a couple of these. Just scrolling through, trying to see. So, what was the most difficult barrier you found when trying to actually create the GSU?

RH: I kept coming up with reasons why they wouldn't let us be recognized. They wanted all the officers to go through training. It's kind of like, are you really asking us to go through because then you had to identify, okay, which group are you with? And it was not, I lived in the dorm at the beginning. When this was all happening, it was like, Okay, I didn't really want. Yes, there were guys in there that were gay and bisexual, but we all kept each other secret if that made sense you really didn't want to be identified. Back then everybody knew everybody's business. I don't know if it's still that way. But then it used to be a really small campus. People knew everything about people. It was like, people did not want to be a target. It wasn't that you weren't priority, it was like, okay, do you really want to get beat up. Every time you go in a building, and you want people to call you fag, that kind of thing. It was not, it was a hostile environment, really a lot of it had to do with why the administration was Dr. Thomas didn't want the gay organization.

You had students write letters, there was an organization that got formed, that was signing petitions against the organization being formed. They were very vocal. Somewhere in here, I have the picture of the because that Isabella had seen that picture of, we have this picture right here of where stop the gays that was actually in Ferguson, where they had set up a table where people would sign a petition to keep the gay organization from. That's the real picture. That's not fake stuff. So anyway, that was really hard. So, I would say just the barriers that they would put up, it was like always one more thing they wanted us to do to be recognized.

AH: Was the GSU open to transgender students or students that didn't fit inside the gender binary?

RH: Yes, there was one individual that he would dress in female attire, and that was fine. It was like, he was part of us. Yeah, there were people that because we were all very familiar with drag shows and that kind of thing. When I first saw him, I thought he's just living openly as a drag queen is what I thought. I didn't, I had not had that experience with a transgender or anything like that. That was very different back then. He was living his life, and we accepted him dressing the way he did, acting the way he did. There was nobody that said, oh, he can't be part of our group. Because we may not have had the full understanding of that. I would say we were very accepting, but it wasn't like there wasn't any recruitment or anything, because you have to think there was any way he got invited, because someone knew him. He was always at our meetings and fully participating in that kind of thing. But it wasn't, he was the only person I remember ever at least dressing in a certain way

BS: Did he ever ask to like use other pronouns or did he always just use he/him?

RH: He/him. Never and you have to think about it, that to me, that would even be a different step. Even coming into the gay identity versus, okay. He was in a community that accepted him, I guess, is the way I look at it. And when you're oppressed, you accept a life, if that makes sense, because it was like, Okay, if they make fun of him, or put him down, they're gonna do that us. So, it was like we've got to be supportive of him, even though we may have not fully understanded. At that time, I was a male wanting to have sex with other males that wanted to be male, and I was, I was here to think about at that time, the gay guy in the jeans and the wife beater t-shirt. That was the thing if you went to the bar, everybody had jeans on? Yeah, , white t-shirt kind of deal. When he came to the meetings, he was like, he was very different as far as dress is concerned, but it wasn't like, nobody was against him. I guess that's what I'm getting. But there wasn't any outrage to our community because we didn't see anything. He was the only person, but he was part of our group.

BS: So then, what did you see in the differences with the GSU on Alabama's campus versus like, Georgia?

RH: It was really funny because I was going back to my papers and that sort of thing about being a pack rat. Right? Do you want to start being a pack rat now? So, when you get to be old like me, you’ll I found things that you didn't even know you had because I actually found a letter from the guy at. So, when all this had happened to me here. It was that okay, I wanted to get my MSW. So, we went to the University of Georgia went to University of Southern Mississippi first and interviewed and it was like okay, this is worse than Alabama, we can't go here. So, then we went to Georgia, and Georgia they had an out lesbian that was the coordinator of the graduate school. I told her, we came in as the gay couple that had got kicked out of Alabama. It was real funny. I couldn’t make-, you had to keep like all A-B averages to stay in graduate school. So here, I would just keep getting C's and D’s because back then you can’t. It wasn't like you to test, you had to write papers, but my paper was never good enough. My partner at the time, he said, let me write both papers, and you choose the paper. His paper got an A plus. He wrote this, he wrote the paper I submitted, and it got a C minus.

It was obvious that the whole thing, the system was set up, they're going to fail me. When we went to Georgia, it was like okay, now we were out. We're well known now, because we really were coming into University of Georgia. They knew who I was because I got kicked out I came in on probation status, because I got kicked out of the University of Alabama, graduate school. Until my story checked out and Georgia to me was way harder than Alabama, as far as the class work. We wanted to find out the gay organization while I found out its Georgia State, which is in Atlanta. We went to the Athens campus, where the main campus of the university, and I couldn't find anybody, , you saw gay people, but nobody knew anything about an organization, . We got to know gay people, but nobody knew anything. So, I'd wrote a letter to the Georgia State University person there. And he was the co-chair of the Student Alliance at GSU. This is dated back October 26, 1993. Anyway, he doesn't know he said, there used to be groups at the university, but he didn't know of any active group. So, we started the group. So essentially, Alabama started the group, which was me and my partner, and we would have meetings at our apartment. In Athens-

BS: This was Georgia State, not University of Georgia.

RH: Yeah, but what it was is I couldn't find anybody at University of Georgia, but I had got this address. Back then we had to do placements, field placements that was part of your grade. I was placed at Scott mental health center on Scott Avenue in Atlanta. I ended up living with John Howard, I got information, there's a park and he was an openly gay man in Atlanta. They named a park after him, but I stayed with him for the first week. Then I want to stay with Caitlyn Ryan. I don't know, she's a big lesbian. She got her degree from Smith, and she was in Atlanta, working with eight Atlanta. And then she went to the clinic in Washington, DC, a big person in social work. Anyway, I lived with her and her partner for a few months, while I was doing my field placement, I guess the differences were, , after having such a good group in Alabama, and us all being supportive of each other and everything. As we try, everybody was so people were even, I think more scared in Georgia than they were in Alabama. You had they were still dealing with it was it's weird. In Georgia that you're still dealing with a lot of racial stuff there and so I wasn't used to that even though how grown up in Alabama and everything here.

It was a different thing there. And I really do think the undertone was you had a large upper middle class black people in Atlanta, and I think in some ways that added a different dimension to the whole conversation. That makes sense. I mean, how people felt threatened and so there wasn't the support there. They had to really work about okay, we can because I remember people bringing their books, it was like people avoided eye contact when you first. In Alabama, we were all just hugging on each other. We were all just really together. In Georgia, it was really there was more divide. You didn't, I didn't feel like the men and women were supportive African Americans, if you've still felt like there was a lot of differences, even though they'd be a group, it wasn't congealed, like it was in Alabama. I don't know if it was just because the atmosphere here was so backward and stuff that we just felt like we had to be supportive. But they are there was more divisions, if that makes sense. So, there weren't people to me, they were not as friendly with each other, even though I was part of getting it started. It would be like some people were drawn to you. But other people were really still in the closet, and still just really careful if that makes sense.

AH: How was the HIV/AIDS crisis handled in Tuscaloosa? And then was it different from Athens?

RH: You have to think about it this time. I remember, , we're coming out of the hippie era, free love. We were all young people, we wanted to experiment. We all enjoyed ourselves. So, there was a lot of, I guess, what you'd call free love of, if you have not dated like the normal heterosexual started having sexual experiences with other teenagers. Let's just say 15-16 even though, and when you don't have those, and then you're in your 20s. Then suddenly, you can do what you want to do. It's like, you kind of go wild, and you enjoy everything. So, get me back on that question.

AH: It was how was the HIV/ AIDS crisis handled?

RH: Okay, so what happened was in 82, we had you just started hearing about the gay plague. But it was it was in New York, it was off somewhere. So, people didn't think anything about that. I mean, people here wasn’t exactly flying to New York? And I mean, yeah, it wasn't all that. So, you thought that. And people really didn't know what it was. I mean, it really was a little bit later till they started calling it that. And you heard about cases of gay men and getting sick, but you didn't really know what it was, but it was like, okay, that's not gonna be us.

Well, when I was in Athens, I get a call from one of the guys that I had had sex with here in Tuscaloosa. He says, well, I need to let , that I tested, and I have AIDS. And it was kind of like, well what is that? , I mean, I really didn't understand. So, we started hearing more. So, I've got all kinds of articles on that, from people saying it's gods punishment. , these are just different things. I'm sure you probably have seen these kind of articles and stuff. Anyway you can look at this, this folder, but somewhere in here, I have a track of where, , they're saying it's God's punishment on gay people. For acting out for homosexuals, it's against God's rules and stuff. So somewhere in that track, because I kept all that stuff, and you can see that so that might be something that I want to look at and see, but it was really one of those things where people you didn't know you didn't understand it, because it was always off somewhere else. I remember when we got our apartment in Atlanta, we were in our last semester of graduate school, and we got an apartment down on Charles Allen. So, it was the gay part, Midtown was the gay part of Atlanta and people would go over to Piedmont Park right across the street have sex in the park. I mean, because where else, meeting people, and so we got invited to a pool party. Here I am a young student. There's all these gorgeous men laying around this pool in the backyard. I started noticing that they all had like big bruises. on their legs and arms. It was cancer, , the different carcinoma, whatever it's called. They had that on there, but you didn't, but they looked healthy. Then they started dying like flies. You saw people that you knew and go into the bars and stuff, you would see people. They'd get sick but they look healthy. Then you’d see them two months later, and they’d have lost 40 pounds, didn’t need to lose 40 pounds. They would die. So, it became real scary. Just the idea, but as people really still didn't understand, initially, how it was transmitted. People didn't know if it was drugs or what it was, and that kind of divert from the question is, that's how I ended up.

I ended up doing aids work and went to eight Atlanta and participated to have different fundraisers, that kind of thing. Then later on in my career, I was Director of Client Services at Nashville Cares in Nashville and was there and worked in that community for a number of years, and then went to Vanderbilt and started the day treatment program, first gay treatment for people with AIDS. Really, in the south, and so I would connect with people, , in New York and get their information and stuff and , gain the information, but people don't really understand it. But one of the things that I noticed early on was that if you were to, back then people, if you had money to travel, gay men would go to New York City or to Houston, and or Dallas, and so if you went up north, and ended up getting AIDS from that part of the country, you tended to live a long time. But if you went to Texas and had sex with somebody and caught AIDS, you would die. Real soon within six months. I started reporting this to people about how I would notice because I do social histories with people and find out that Okay, where did you first? Where do you think you got exposed, and those that said they got in in Texas, but what happened was those people more than I can figure it out is they had dated people that had come from Cuba. Cuba had sent a lot of people to Africa, to do work in the US medical doctors and that kind of thing. So, some way through the communities and stuff had spread that way, and so they died sooner. So, now it's kind of accepted people talk about there may be different strains of HIV. Back then it was like just all aids, but I just noticed people were dying quicker and stuff, but it was, as far as here. By that time, the end of 83, I'd already started over at the University of Georgia at that time. So, when I got that call, it was really strange. I assumed that I had AIDS. So, I just accepted that. I thought, okay, and if you think you're gonna die, and back then we really didn't know about safe sex. I mean, it was not preached to us about safe sex or anything. So, well you better have all the sex you want because you're gonna die, and nobody cares. It's God's punishment on you for being gay, even though you felt like you were always this way. Nobody made you that way. So, it was that whole thing, if that makes sense.

BS: Why was Texas such a big hub for gay people?

RH: Because it was, they just had a large community there. You really, it is hard to understand sometimes how that's happened, certain cities have larger communities than others. Then there's spikes and if that makes sense. You think that there's a whole generation of my people my age that died out. There's a lot of people that are younger than me that are in their late 40s, early 50s. Then you have those that are even older than me, but most of the people you don't find many people my age that are openly gay that lived through the AIDS crisis. They didn't get AIDS. I never got AIDS. And so, when I went to get tested in, when I went to, I went for several years and never got tested, I just assumed I had it. So even when I worked at Nashville Cares, I just assumed I had it, I was working with people every day that had it. It wasn't that I was ashamed or what I just assumed I had it, and by then I was doing safe sex because we had learned about safe sex and stuff. I went, got tested, and back then he went to the health department and got tested, but you didn't give them your real name. Because they would track you down.

So anyway, of course, the guy that was doing it was gay and he knew me because I was Director of Client Services and Nashville Cares. So, I gave a fake name, he goes out there and laughs when he calls me, and I stand up, to go get my result of my tests. I was shocked that I was not positive because I had had sex with folks before. Well, here in Tuscaloosa and but also in Athens before we even knew that they had had AIDS and stuff. So, it was really strange of getting to know people that, a lot of the people that I dated that were my friends died of AIDS. I don't understand how and that's one reason why I like to do these kinds of things is to talk about because, to me, there's this generate a large part of my generation died out, didn't make it, we had the AIDS quilt and that kind of thing. He was really moving these to put it out on the mall, they brought sections of it to Nashville, and had it displayed and stuff. I always give Dolly Parton credit because she ended up giving a lot of money to the gay community, her hairdresser and stuff was the end there. But she was always very supportive of the gay community and gave the money to bring the quilt to Nashville. Now I know people don't know it because she didn't advertise it, because her fans most would not approve it, especially back then. But she was very liberal and very supportive of the gay community.

IR: Okay, what are some things that GSU did during the AIDS/ HIV epidemic to like, help out? And what backlash did you guys receive from helping?

RH: I think the main thing was, people were saying you, you get what you deserve. So, people tried to be supportive of one another. Back then people really didn't understand how you caught it. If somebody got it, then back then if you went into hospital rooms, and somebody had aids you wore a spacesuit, you had the mask on, you had the whole uniform on, so you look like you were walking on the moon. And so, I remember my first hospital visit that I made. I was a license social worker, it was like, I'm coming to see my friend, I'm not wearing that. Cause of where, you have to wear that and I said, first of all, by then we had known how we were getting exposed. I'm not having sex with them, I'm coming to save in the hospital room, I don't need to wear, there's no reason to do that.

I talk to my mother at that time, about the fear because she was a school teacher and all that was coming up, the school teachers felt like they needed to know what kids in the room had AIDS, because if they got hurt on the playground they might get exposed or other kids might catch it and that kind of stuff. I said, first of all, you need to assume every kid in here has AIDS. Then you're going to wear your gloves every time you bandage them. That kind of thing. So, it was a big education thing amongst people. I would tell people, you never know. And it's really strange. Where I remember the first case I had of where an elderly person had contracted AIDS in the nursing home. It's kind of okay if anybody knows about nursing homes. There's a lot of activity of the nurse, I mean, it’s a lot to think about Mee-Maw and PawPaw out doing things, but they do things. We're all human. So that whole scare of that. There were different things set up in regard to like care teams later on. It was an involvement of where people would get together and support somebody, but usually, you had to know somebody, like if you knew that they had AIDS, then you get their friends together and say, how can we buy their groceries? How can we make sure that they are getting their medicines? That kind of stuff, so it was informal if that makes sense.

BS: So then why did you decide to stay in the south even after kind of like all your experiences, specifically Alabama.

RH: I think the thing is, and this is the thing I want to encourage y'all is every day, I'm a married gay man in my community, in Scottsboro Alabama, and it's up in the northeast corner of Alabama. And so, People have to, I live in a very nice house and on the golf course, my partner's a nurse at local hospitals have been there 37 years, everybody wants to come to our holiday parties that we have. Because I never know how it's I half the people there are Trumpers. But they are fascinated with us. And to me, it's more of an educated, it's more people wanting me to go and I love like going to New Orleans, we used to go eight times a year back when you could fly for $90 round trip, we fly to Birmingham and go, at least at eight times, because I love being in the gay community, I love going to where I feel like we have a large presence. And Atlanta to me now is a little diluted, compared to what it used to be when I was there in the mid-80s. It was mid-town was everywhere you went was gay. I mean, gay couples lived in every house. So, it was a real community.

And so, I wanted to educate people if that makes sense, I want them to know, I pay my bills, we mow our grass, we were involved in all kinds of things. I like people to be shocked if that makes sense. I mean, when we went to the cemetery to buy our plots. My dad died two years ago. So, it was kind of okay, we need to go ahead and get all this set up and everything. So, we went and got the plots, and so we wanted to have our tombstones. And but then we didn't know okay, well, it's going to have two men's names on the tombstone. So, we didn't want people bashing it with a sledgehammer and all that kind of stuff. So anyway, we put it on there, we have our names on there and dates of birth and stuff. And it'll have the dates when we pass. But in the middle of it says you too because it's normal. I always say love you to my partner. And he goes you too. And so, we put a big U and a two on there. So, the lady that was doing it. It was really funny. She's an older lady. She was older than I was. And she said somebody says, I love you. And then they say you too. I mean, she knew that without us telling her that. It was like, okay, what we, like, I'm retired from the state of Alabama. So, when I applied for insurance from our partner, and he was like, okay, well tell me your wife's name. And I said, well, I have a husband. So, it was educating people, and it was a real battle. They came up with some, I guess every there's things every day, I have to deal with that I want to make it easier for you y’all’s generation. It’s like when I signed up for the state employee's health insurance. It was like, I was telling the lady that call back case manager, I said, we're a gay couple we've been, we're legally married, do you need to see the papers, and it was amazing like when we bought the tombstones, we had to send a copy of our marriage certificate. It was like, there was really no reason to, instead of fighting on them like, okay, I want them to say it's legal, it's registered.

BS: What year were you able to, like legally get married?

RH:16. And so it's coming up on seven, seven years, we've been together for over 20 years. But I never thought in my lifetime I'd ever be married to man. And that was the first thing when my grandmother found out she was very practical, Jewish lady, she was it was that, okay? Why don't you just marry a woman? And it's kind of, and you can do what you want to do. I mean, it was weird her saying that because she was a very liberal lady, but her thing was, and it was kind of like. I think that would be really unfair to her. Unless she was doing something. And I think that's what my grandmother was telling me. Okay, she'd go off and do her own thing I f you married a woman. But it was like, okay, how you gonna find somebody that was willing to be in a fake marriage kind of thing, if that makes sense.

AH: Is there anything you would change or wish the GSU had achieve in its time either in Tuscaloosa or Athens?

RH: You have to think about the time I keep going back to that it's, it's almost like we were almost we're almost snuffed out here in Alabama. They did everything they could to stop it. And I think if it had been in ’84 when AIDS really got started, it probably would have died I'd right then. But I think we had already had; people had already started forming a community and being supportive of one another in some saying we all got along. I mean, we didn't divide. I mean, you really weren't divided. You didn't think of these are lesbians or, or these are African Americans. You didn't think you didn't identify your friends that way. We were all friends. We listen to Michael Jackson together. It was amazing to me when I was talking to some young people. One of my coworkers, teenagers in that in Michael Jackson, she's African American is that how do you not know Michael Jackson? Billie Jean and I was like, okay, that was our thing.

But really, that was my thing is just encouraging people now to be themselves and know you're gonna pay a price for that. Now, it's slightly easier if you people can say, well, why don't you just go to New York? Because I, when I was at Nashville, I had people that would come and they'd say, why don't you just come to New York, you'll have a lot, a lot easier life and I'd have young, gay professionals working for me. And they would move to New York, and they said, Ross once you just made me so much easier. And stuff was like, okay, I like being where people, I challenge people’s idea of what a gay person is. And I've been surprised, See, back then he was like real Louis, you knew each other, you had a lot of straight people that were very supportive, too. Not everybody that was on my list was gay, or bi, or whatever. You had a lot of straight people that were very liberal, that were supportive. And that's been the change to me, or the question I have, because I, until December of last year, taught classes, and up in Huntsville, on the campus there and do clinical supervision with social work students. And I was surprised at how conservative the students are. And I made, usually I don't go around telling my personal business. And but I would start class. So, this is my name and stuff. But I want to tell you a bit about myself. So, I will tell the students that I was gay and that I had a partner, and we were married. And I got some blowback on that. It was like, why are you sharing that? Well, first of all, it's a clinical program. So, you need to know you will be working with gays and lesbians and transgender folks. Don’t assume everybody who walks through your door, especially with children, are straight. And so, I did that. But I was really surprised at how many how I had some problems with social work students that had problems with me being gay, and essentially talking about being married to a man like, oh that’s gross. It was like, okay. And I could tell the people back at the university, this student said these things, and I would just have real concerns about them. Because they're going into the field of social work, where you're supposed to be accepting and that kind of stuff. And they're already saying things that I have concerns about. So, I guess that.

BS: Are you happy with the route that GSU has taken today with his current iteration like QSA?

RH: I'm not as familiar I guess, as I need to be. I've seen, I go online and look at things. And I kind of just bounce it back against my history. And it's kind of I wish people would be more. I grew up when we marched in Nashville. They would get if they thought you were gay, they would get rid of you at Cracker Barrel. And so, and back then it was 84. They didn't have female managers. They didn't have African Americans, only African Americans could only work in the kitchen and buss tables. They could not even be waiters or waitresses. And so, some people got fired, and so we started marching. And we'd go every Sunday because that would be the busiest time people got Cracker Barrel across from Auprey land, they have a big Cracker Barrel there that's when the ad was found in Lebanon in Tennessee and so we would go in March, and stuff and so Cracker Barrel finally changed its policy kind of like Chick fil A issue when it came out, , when their issues and stuff and realize.

So, I wish people would be more stand up, but everybody has to. Coming out is everybody's own issue. You don't I don't believe in outing people because everybody has their journey, even though it makes me mad. When I know people are what I call getting the benefits of being gay, they're having sex with all these people, but then they want to say, well, gays don't deserve the same rights as everybody else, but they're doing everything in the privacy. And sometimes I wish that everybody that was in our community could turn gay, and there'd be a lot of people that were gay, and then nobody knew just was [inaudible]. I really do wish that because it really bothers me, people being the cause it's fine that when people persecute other people, and to me, that's the thing I think the younger generation needs to realize, you would think, because, oh, you're going to work and you'll know somebody gay, that's older, or lesbian, and you find out that they're not supportive of you, that they actually will may try to get you fired, or whatever, say they feel threatened by you. So that was one of my experiences because I thought, well, we’re all one community, and we'll be supportive of one another, and it's not that way. And so, I mean, that's just part of it. So, I would just say, encourage you to be yourself, and now you'll pay a price because there's jobs that I didn't get.

And I remember interviewing for one job went back four times. And finally, I was there last, they hired three other people before they hired me, even though the secretary liked me from the first. And so, she had told me she was, there's 10 other people. And, she had saved for I was on the list. And so finally, they hired people. So, it took about two years for them to hire me. And I was director of children's services for a 40-county mental health center, so I was very high profile. So, I thought the reason they weren't at Vanderbilt at the time, and me being openly gay, and overall, the children's programs, that's what they're why they're not willing to hire me. And so, I went in, and I said because I was always afraid to get fired. So, I'd be buried in the job interview where they'd say, well, tell us about yourself. I've got some, I've always talked about being an openly gay man, I'm Jewish, and I'm a Democrat. Well, I remember the guy that, that hired me, he goes, well, I don't have any problem with you being gay or Jewish, but I do have probably a bit Democrat, but he hired me because I was the last person that get hired. But anyway, there's that I just encourage you to be yourself. Realize there's gonna be ups and downs. It's easier in a larger [inaudible].

I love San Francisco and I brought all kinds of newspapers and stuff from there so you can actually see that things were different back then. Here’s the newspapers from there. These are the Atlanta gay center newspapers. I have newspapers from all kinds of places. And you have the map? I don't know, y'all probably don't know. You probably heard of RuPaul. He worked with Charlie Brown in Backstreet in Atlanta and Raven was there. And so I was, I was there at the Charlie Brown, RuPaul, back in the old days. And so anyway.

BS: I think that was all the questions I have. If there's anything else, you wanted to add? Final thoughts?

RH: It’s just I mean, I, it's just so much. I mean, there's different things. I could go into a lot of details about different segments of things, but I guess my thing is, it's a journey. My thing is, I never wanted to be regretful if that makes sense. And so, I wanted to live my life. And so, by staying in Alabama, staying in Tennessee, and Georgia, was forcing people to deal with. It was a lot harder in Alabama instead of just to deal with it, but it was like I want people to know. And like, I do estate sales, and I got totally out of social work. And so, I worked with some people that do estate sales. And so, when they were cleaning up, oh we found all this, straight guys, he was he was saying “Oh, I found some pornography.” And he was talking about seeing the women that kind of thing is, and I said, well, I don't care about seeing it if it ain't got any man in it and the women that I was working with just laughed and stuff. But it was like, he was still assuming even though he knew I was gay. It was like, okay, do you want to see this? I'm like, no, I don't want to see, I don't want to see that. Yeah, so I guess what I'm trying to say is, every day, people and I see young people, there's people that work in our Walmart, in Scottsboro that are gay. And I try to be encouraging because just no one did. Okay, here's a gay male couple that's living openly in Scottsboro. We pay our bills, we are respected, we live in a nice house. And I want them to know, they can have that life. So, I guess that's my thing is, now I want you to know that regardless of your orientation, or how you identify to live your life. Don't have regrets. Because you will wake up, sometimes it's hard to believe I'm 67. I know, think of myself, I still think, okay, what am I going to do and that kind of stuff. And I want people to realize that the time flies, it really does. And so you'll be 30 and then you'll be 50. And things happen. And, and I take pride in, I love the new HBO thing, or Showtime I guess, show Fellow Travelers. I don't know if y’all have seen that.

RH: Also, see I have also I have an uncle, that's gay, and I didn't know that growing up. And it wasn’t until in college that I learned he was gay. He works over in Vietnam, and he went to work for the FBI in Washington and stayed there. So, I didn't know that until I was in college, I guess when I started down here. And I found out that he had a partner and they have lived together all of these years. He worked for the FBI and his partner worked for the Treasury. And so it was.

BS: So, with these documents, you were talking about making copies? Would you be more comfortable if our professors made copies and then we got them back to you? Or how exactly would you want to do that? It’s whatever is like the easiest, most comfortable for you.

RH: We were just all accepted so people didn't think about, okay, I'm having sex with a black person, you were having sex with your friend. Where in Atlanta, it was more you’re having sex with a black man. And I mean, I guess that sounds weird. But I didn't always, when I think back about, I don't really understand what that dynamic was in Georgia, that was different from Alabama, because you think it would be about the opposite. It'd be worse than Alabama, but it wasn’t.

Yeah, I'm fine with it. I guess what I'm saying is, I don't know what's all in here. It's all mixed together. But anyway, these are just—

We couldn’t go on dates because where could two men go and eat together? And I remember for the first time when I came back to Alabama, and I was working for public health and there was a guy there at work. And I mean, he was married and everything. And we went to lunch, and I said, you want to go eat lunch? And he goes, no. And, and I'm thinking, well, maybe because I'm gay that he doesn't want to go eat with me. I ain’t wanting to have sex with him. I didn't say that. But I found out later, he was afraid that somebody would think he was gay because he ate lunch. And it's like, I hope that everybody I eat with the people don't think I'm wanting to have sex with them. Because I mean that was not. I wasn’t thinking, I was just thinking like coworkers to eat. But anyway, yeah, I'm fine with that. And so, some of it’s—

BS: Is there anything you do want back? For you to keep personally?

RH: Yeah.

We were like student assistants and that kind of stuff. We were part of the organization that would get us into different things.

I'm against adults having sex with children. But there were people in the gay community that said, but they have pubic hair then they can have sex. And it really bothered me because you find I mean, it's just like in any community, you're going—