Cookbook Review

By Tyler Thull • May 2, 2018

Russian writer didn’t pander to clueless American cooks

A review of Samovar: A Russian Cookbook by Elizavetta Dmitrovna

I learned to cook by watching people do it and by reading detailed recipe books like Joy of Cooking and Mastering the Art of French Cooking. These books both give detailed, clearly worded instructions that even novice cooks can follow successfully. When I am learning to work with a new type of cuisine, I need to either see someone prepare the food at least once, or I need specific instructions in recipe form.

When I wanted to learn about traditional Russian cuisine, I sought out a cookbook with a few criteria. The cookbook had to have traditional Russian dishes that I did not recognize, it had to have conversions to American ingredients, and it had to have clear explanations for the execution of each recipe. As I had not previously experienced Russian cuisine either by eating it or by watching someone make it, I needed to find a well-written cookbook.

I went up to my favorite bookshelf on floor 4M of Gorgas Library. This row of books is the academic foodie’s Mecca. I have idly perused the contents of this row for the past three years of my college career. I had not previously searched for a Russian cookbook, however, and I was mightily disappointed to discover that there was only one. I, a spoiled American, love having lots to choose from. With only one cookbook to choose from, I felt sort of like the chefs in the Soviet canteens who were only allowed to prepare recipes from one government approved book. I decided to roll with the Soviet cook’s mentality of making do, so I checked the book out.

The tiny, red volume bound in hardcover with an orange etching of a Russian teakettle on the front is titled Samovar: A Russian Cookbook by Elizavetta Dmitrovna. First of all, it is important to note that this book was published in 1946. Let’s take a second to think about Russia in 1946. War. Soviet control. Famine. Cities buried in rubble and ice. The Russia that this ex pat author writes about fondly in her introduction is the Russia from her childhood before World War I, not the Russia in 1946. This book for Dmitrovna seems to be an act of defiance against her changing country. She wants to keep traditional Russian cuisine alive in her memory and in her new home in the US.

In her introduction, Dmitrovna dedicates one paragraph to background. She says that she left Russia when she met an American military man and has not been back since, but that she still cooks exclusively Russian food. She then regales readers with fragmented memories of the Russia she remembers from childhood. She describes the tea served in samovars, the rum and lemon that keeps Russian tea exciting, the tall Easter bread that families take to church to be blessed, and the celebration of saint days instead of birthdays. At the end of her introduction, Dmitrovna claims that her cookbook is full of recipes that are, “very simple to make.” The recipes following the introduction debunk that claim immediately.

The voice of the cookbook is stilted. The author writes with English as a second language. This language barrier is perhaps the reason that Dmitrovna’s instructions are as short and personality-free as they are. Compared to Julia Child’s narrative in one of my favorite cookbooks, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, which includes potential mistakes, funny stories, humorous ingredient overviews, and exact measurements (God forbid), the writing in Samovar is as barren and icy as a Siberian tundra. For example, the recipe in Samovar for sour cream waffles is exactly two sentences long and includes no cooking information at all. The recipe is as follows: “Whip on ice sour cream and mix with uncooked egg yolks and flour, sifted twice. Whip whites to a stiff froth and fold in.” I wonder if Dmitrovna’s editors restricted her to a page limit. There has to be some reason she gave such insufficient instructions.

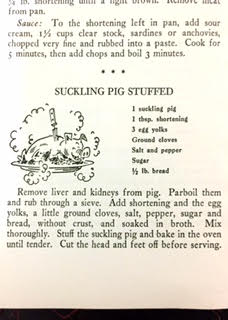

The waffle recipe is not the only one that leaves out crucial information. A recipe for the preparation of an ENTIRE stuffed suckling pig is six short sentences long. After reading the recipe, I still have absolutely no idea how to prepare a suckling pig.

I do not know how long it should cook. I do not know how to differentiate the liver and kidneys from the other organs. I do not know if I am supposedto remove all of the organs or just the liver and kidneys that I have to parboil and rub through a sieve. I also think a measurement for ground cloves is incredibly important. If I followed these pig roasting instructions exactly, I would have a major culinary disaster on my hands. The majority of the Samovar recipes are as laughably inadequate as this one is.

I understand that Dmitrovna expresses her nostalgia for her childhood in her homeland through these recipes. I sense that Dmitrovna’s goal is not to inform American readers about Russian cuisine, but to reminisce about her favorite foods from home and to help other Russian ex-pats cope with the different American ingredients. I get this sense because, unless you grew up watching your babushka’s skilled hands whip these recipes into shape, you would never, ever understand how to make them.

Nonetheless, I decided to make two recipes from this book. I chose two recipes that I had had in other settings before, and I tried to make them using Dmitrovna’s methods. First, I made borsch. Next, I made carrot soufflé.

I am currently having a love affair with beets. It is pretty hard to go wrong with beets in borsch. I have now tried making it two ways, once the more complicated way detailed in Samovar, and then again in my crock pot. I understand that Dmitrovna did not have access to a crock pot in 1946, but she would have appreciated one. What took two hours of paying attention to a stove on simmer to make the traditional recipe took 30 minutes of prep with my crock pot. The flavor in the end of both recipes was similar because both recipes required the same ingredients. The one note that I appreciated in the Samovar borsch was the instruction to slice the potatoes thickly. They came apart more than I wished they would in my crock pot borsch because I cut them up too small. This recipe worked. It was more complicated than it needed to be for 2018, but for 1946, it was a functional recipe. The borsch came out of the pot a lovely, bright red color, and the vinegar and sugar perfectly balanced the earthy beets and rich, tender beef.

The carrot soufflé worked, but it was heavier than I expected a soufflé to be. I had never heard of putting cream of wheat in a soufflé. Cream of wheat is an American equivalent for manka, a semolina porridge that was often the only available grain in some parts of Soviet Russia. The recipe lacked instructions for oven settings, so I had to google another carrot soufflé recipe to corroborate. I understand why Dmitrovna included this recipe in her cookbook of Russian comfort foods. The bright orange carrot soufflé warmed me with its sweet, lightly spiced orange pudding. The fatty mouth feel from the butter and the cheese melted on top kept the dish savory, while the cream of wheat added filling substance to a dish that would otherwise be fluffy and light. For all the cookbook’s lack of explicit instructions, it actually managed to include a yummy and doable recipe.

Although my creations based on the recipes in Samovar were palatable, I will not repeat them. The borsch is easier in a crock pot, while the soufflé is more fun if it is kept fluffier without the cream of wheat. While the cookbook is not helpful for a modern American cook learning to prepare Russian cuisine, it does serve as an interesting historical artifact. For practical use purposes, I do not recommend Samovar to anyone who does not have an old Russian family member who can explain the missing components in the majority of the recipes.

Bibliography

Dmitrovna, E. (1946). Samovar: A Russian Cookbook. (B. F. Grant, Ed.) Richmond, Virginia, US: The Dietz Press, Incorporated.