A Thailand in the Rough (Northern Thai Cuisine by Dr. Onanong Tongmee)

By Lyle Lee • May 1, 2018

I am at my wit’s end.

A week spent searching for Northern Thai restaurants in the Houston metropolitan had ended fruitlessly. There were whispers of elusive holes-in-the-wall and restaurants that “did a little Northern Thai on the side.” However, each lead I pursued dissolved into dust. At best, I got a half-hearted papaya salad, with too little papaya and too much salt and many hard peanuts.

I am constantly reminded how fortunate—and unfortunate—I am to be born into such a secretive food-culture. Only traces of it can be found in America, and indeed, the rest of the world. I am beginning to doubt myself. The food-laden streets of Chiang Mai—were they a fever dream? Outside of Thailand there is no trace.

My poor mother (who I have harassed several times now) offers me condolences over the phone: “Our food has never been very popular.” Indeed—all the cookbooks I’ve read, all the restaurants I’ve been too, are far more willing to court the romantic, tropical Thai than her peculiar, mountainous cousin. The Northern Thai, when given a chance to scribe their recipes, submit to popular interpretation. Even in the modern day, their true cuisine is passed down through family and oral tradition—something I find simultaneously admirable and frustrating.

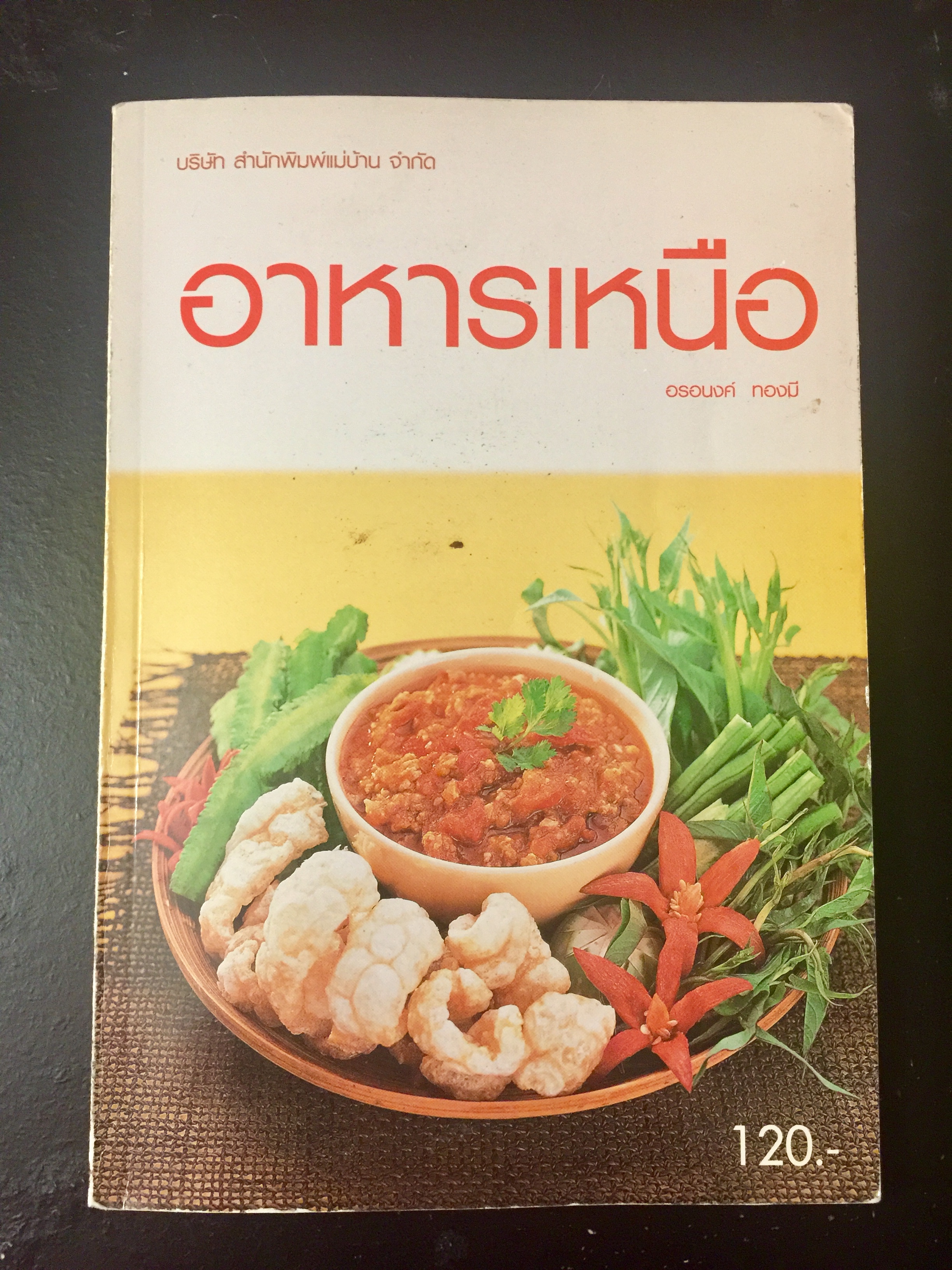

What I am reviewing is the one book I drew out from this mess: eighty-two pages, with a price tag of one-hundred and twenty baht (or just under four dollars). The author, Dr. Onanong Tongmee, is both a professor specializing in ancient Thai recipes and a host of a cooking show. This book is very popular in Thailand, my mother says, and though she knows her own recipes by heart, “it’s nice to refresh yourself by looking at the pictures.” However, there is one issue.

It is completely written in Thai.

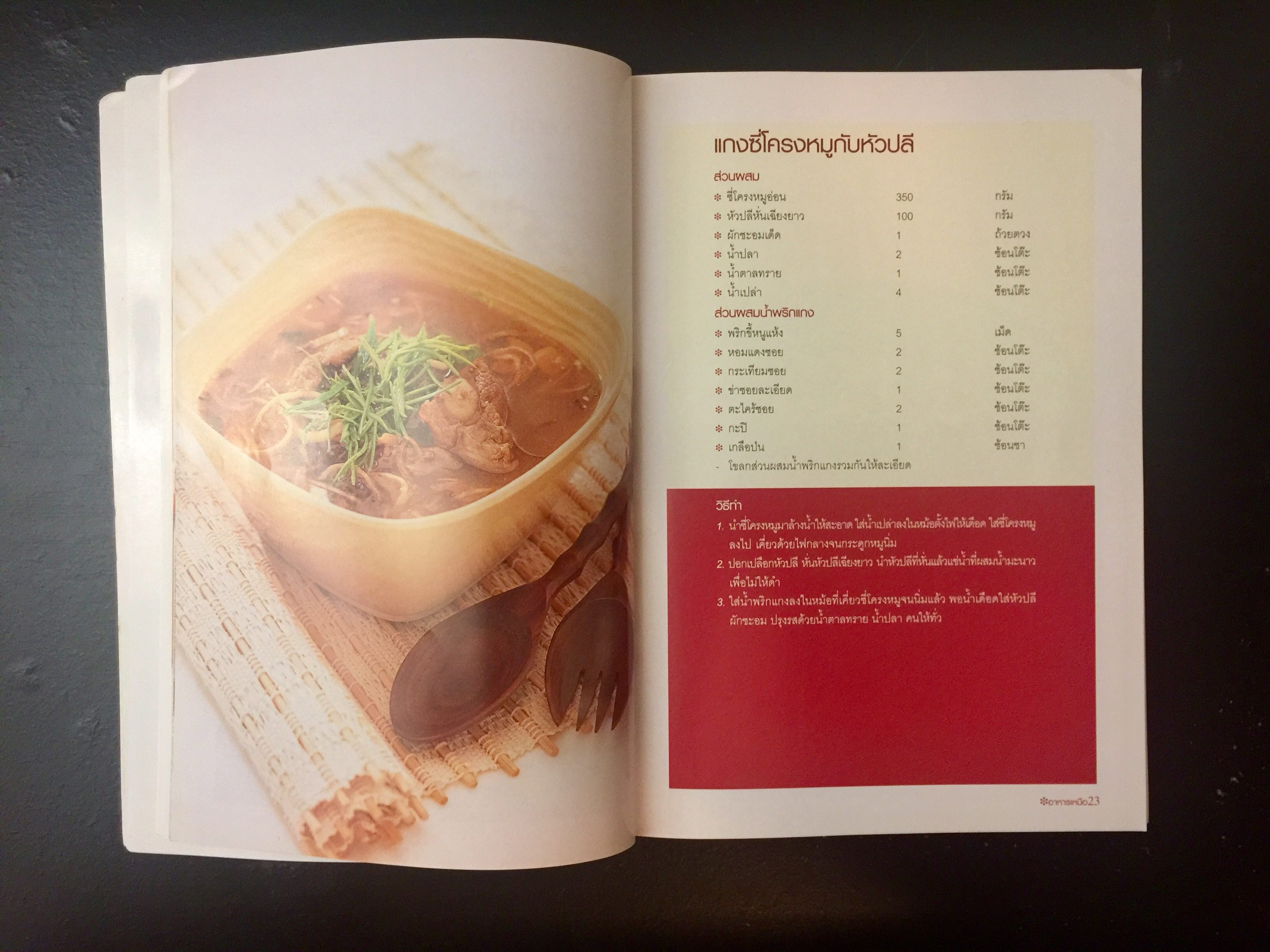

It is a book written for Thai folk: Thai housewives, Thai students, natives of Thailand. It is the kind of book found open next to the mortar and pestle, or slipped under a mug as a coaster. This book deserves to be useful—to be one’s companion in the Northern Thai kitchen. Though the ingredients lists are long, there are many common elements shared between them. The recipes are simple—each is a page long, with no recipe having more than seven steps (and many of them having as few as three).

So why should we, English-speakers, English-readers, consult such a book? Should one go through the trouble of translating the text to cook authentic Northern Thai food?

The pictures are beautiful. Looking at only the cover I nearly deceived myself into thinking this book was written decades ago, given the faded colors and the blocky, simplified text I associate with old Asian things. However, the pictures of the food itself are clean with little decoration, letting the colors of the dish speak for themselves. I was surprised by how many of these dishes I could recognize: sai ua, nam phrik ong, nam phrik num. Even dishes I’m not sure how to name—sweet stewed pork ribs, catfish soup—I can recognize by these pictures.

The style of the book is no-nonsense and to-the-point. The ingredients and steps required for each dish are listed and neatly separated. The use of light colors (beige and white) versus darker ones (red and black) allows for quick consultation, no eye strain necessary. Many modern cookbooks tend to weigh their recipes down with excessive story and fancy fonts, so it’s relieving to see recipes written the way my mother or grandmother would.

Of course, there’s little weight to a cookbook if it’s all talk and no taste. To test its merit, I picked out a dish I grew up with—nam phrik ong—and made it exactly according to recipe. It’s one of my favorite things to eat at home, so I know what it should taste like, though admittedly this was my first time making it.

The resulting dish was delicious and simple to make. I was surprised that it didn’t require any shrimp paste or cherry tomatoes. Given the author’s background, however, it makes sense that only authentic ingredients are called for, rather than what must be imported. Though it was time-consuming to dice the garlic, shallots, and lemongrass for the paste, the actual cooking required little work. All I had to do was fry a little bit of garlic in oil, add the paste, and fry the ground pork and tomatoes.

The juicy tomatoes and crumbly ground pork go well with both sticky and jasmine rice. I could imagine this being served regularly in Thailand, accompanied by a variety of fresh vegetables and some pork chicharrónes. My only issues were the addition of water (which makes the dish soupy and less flavorful) as well as the taste being more sweet and less spicy.

So, is authentic Northern Thai food worth the effort of translation?

In my opinion, yes.