Mu Bing with Lime Chili Dipping Sauce

By Lyle Lee • May 1, 2018

My first experience with Chiang Mai street food was with succulent bits of pork being grilled at an open-air stall—mu bing. The fat was seared to moist perfection and the meat was tender and just a little burnt. Each bite-sized piece was infused with a harmony of strong flavors. Exposed to heat they released an enticing aroma, drawing me, a foreigner and food purist, into the realm of Thai cuisine.

Traditional preparation of mu bing requires that the pork be skewered, grilled, and then bagged in plastic with sticky rice. However, you can still prepare this dish even without skewers or grills or plastic bags.

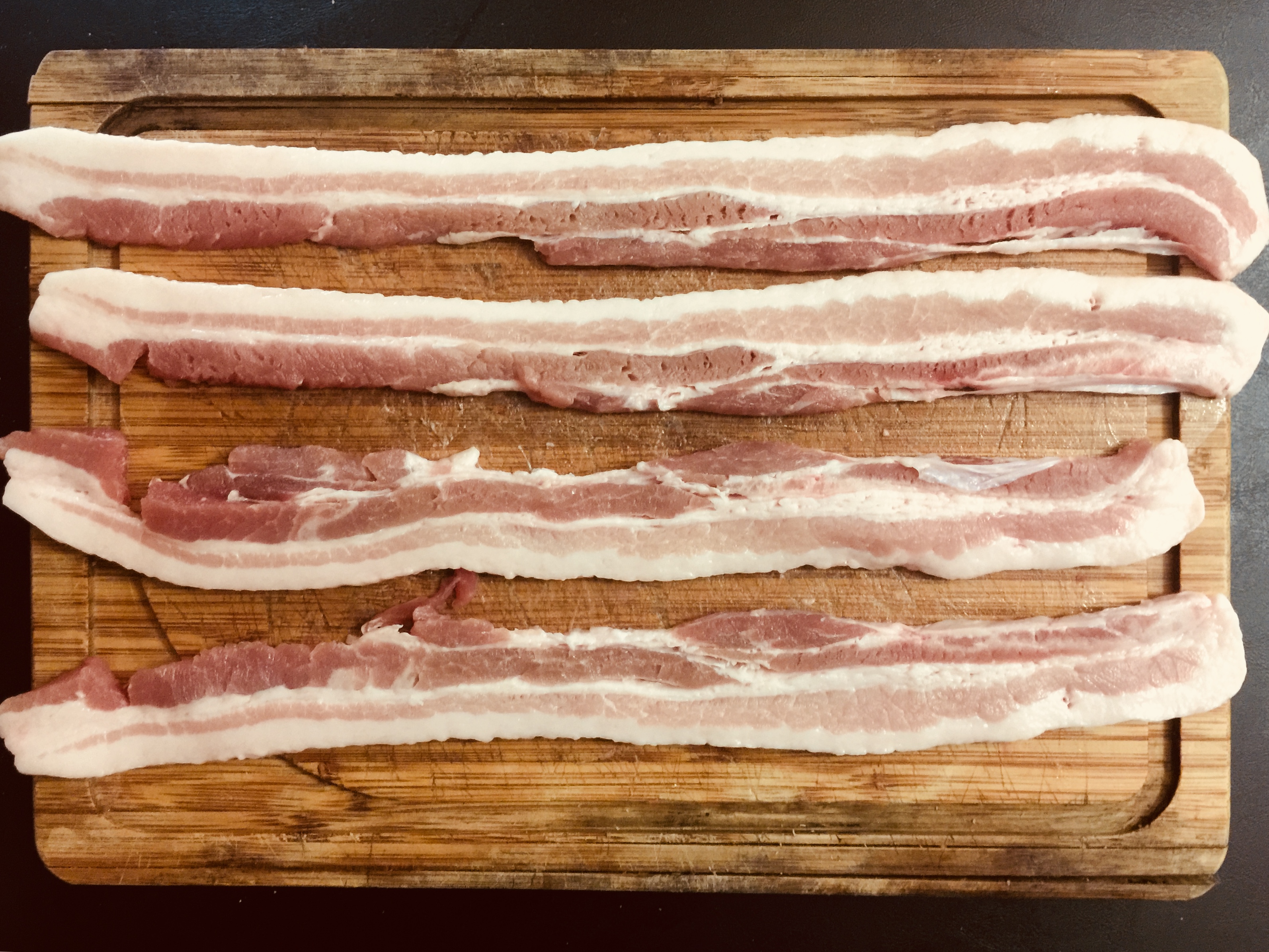

These are the ingredients you will need to prepare mu bing in your kitchen. There are several distinctions that make Chiang Mai mu bing unique: fattier cuts of pork, a thicker and more viscous marinade, and the lime chili dipping sauce it is served with (discussed later). I will be experimenting with both pork shoulder and pork belly as potential cuts. Pork shoulder I chose for good texture and some fat, whereas pork belly is very fatty and nicely layered.

You’ll want to cut both the pork shoulder and belly into pieces the size of your thumb with half the thickness. Ideally, a piece of mu bing fits on a ball of sticky rice (like Japanese nigri) or on a slice of cucumber. Marinade is estimated to penetrate only one-eighth of an inch into meat, so by cutting these pieces thin the meat absorbs more flavor when marinating. Think surface area compared to volume—smaller is better.

It is helpful to cut perpendicular to the grain of the pork shoulder, or the direction of the fibers. This technique helps produce a better texture under heat.

The pork belly should be cut in the same way. Fortunately, for me, this pork belly came in strips like bacon and pancetta. The thickness of each strip was about right, so I set about cutting the belly into pieces.

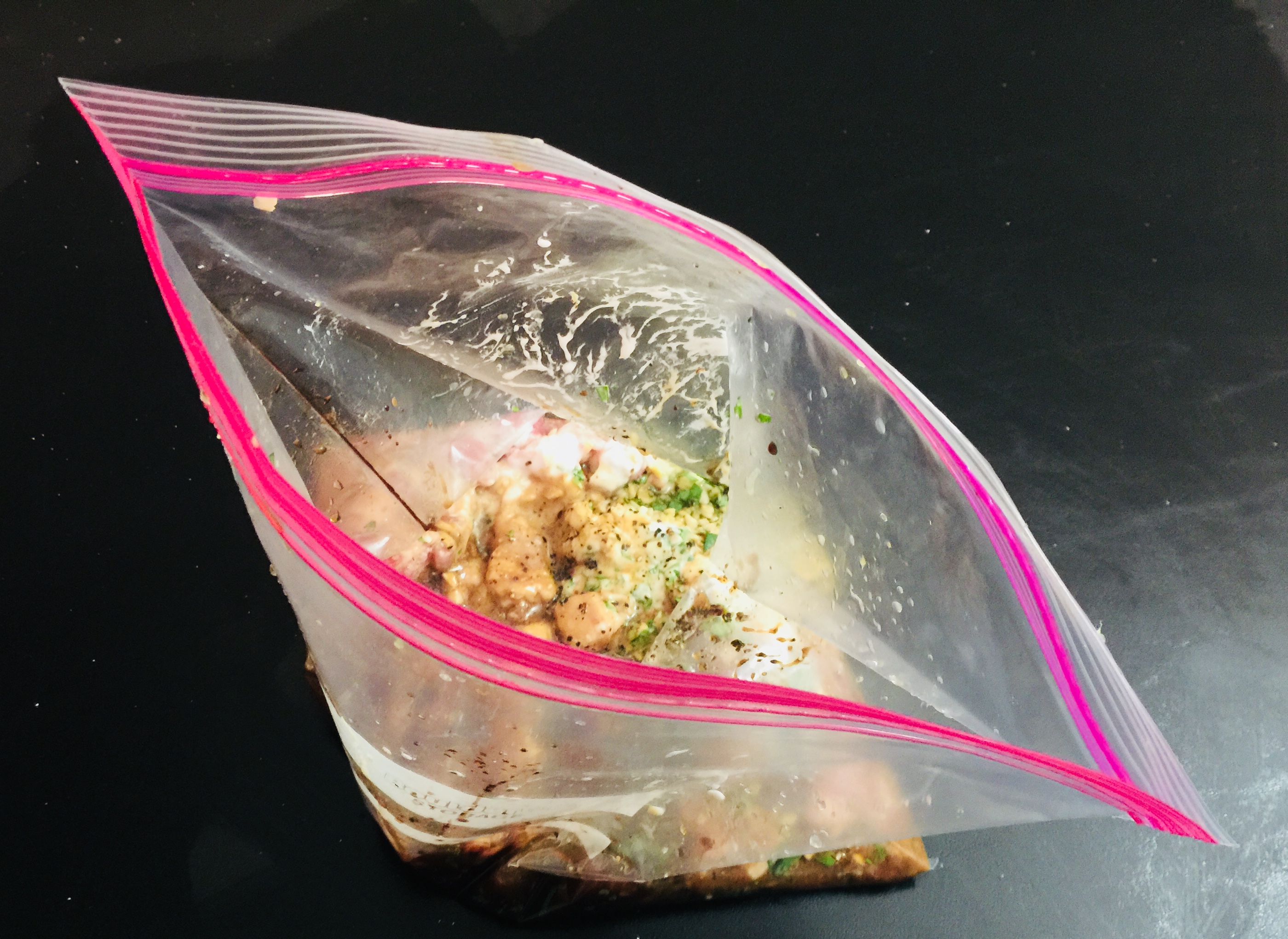

Once you’ve placed the meat in the marinating bag, add the liquid components of your marinade (excluding lime juice). There’s quite the list—put in soy sauce, sweet soy sauce, oyster sauce, honey, oil, coconut milk, and water. You can also use brown sugar in place of honey, though it should then be added along with the solid components.

Different sauce brands have different tastes—you’ll find this is true of all East and Southeast Asian cuisine. Because there are many different ingredients in this marinade, what brand you use shouldn’t matter in the long run. However, if you’d like to duplicate my results exactly, here’s what brands I chose to use.

Healthy Boy Soy Sauce is light, aromatic, and easy to drizzle. It has (relatively) low salt and won’t dry up your mouth like Kikkoman or Lee Kum Kee. Those are “dipping” soy sauces—Healthy Boy is used strictly for cooking.

ABC Sweet Soy Sauce is sweet, thick, and sticky—like an Indonesian molasses. Its main use is in preparing Indonesian sweet fried rice, which is like jambalaya. This and the honey will add sweetness to your marinade. Throw the lime juice in, and you’ve essentially got that tanginess you want oozing out of your pork.

Maekrua Oyster Sauce is savory, with a consistency somewhere between sweet and thin soy sauce. I often pair this with stir-fried cabbage or steamed gai lan, since these are vegetables with good texture and mild taste.

Mince the cilantro and garlic as finely as you can manage. If you have a mortar and pestle, you can grind the cilantro and garlic instead. From my experience, it works just fine if you crush the garlic with the flat of your knife before adding it to the marinating bag.

Cut the lime and add the juice to the bag. I’ve always seen lime cut into wedges like this, which seems to be one cut further than a lot of chefs take it. Essentially I’m dividing half a lime into fourths—however, the way you cut or juice the lime is up to you. All you really need is plenty of lime juice to soften up that pork.

Add the solid ingredients to the liquid ingredients already in the marinating bag. Everything should be in the bag now, and it might look like a bad night at Chipotle. Once you mix it up though, you get this nice color—

Don’t be deceived by the redness of the meat, though. The marinade should be orange or light brown, depending on how many personal tweaks you made. If you waft the aroma, you should be able to pick out each of the individual ingredients with your nose. These ingredients, of course, need time to intermingle and create something special.

The pork should marinate for eight hours, or overnight. If you’re in a pinch, three hours is the minimum for pork to absorb most of the marinade. Because the pork will grill (or in my case, broil) quickly, you can let the pork marinate until about fifteen minutes before dinner time.

If you have access to a grill and bamboo skewers, you can skewer the meat and grill it on medium-high heat for 1.5-2 minutes per side. You’ll want to add three tablespoons of cornstarch (or six tablespoons of flour) to the marinade and mix before grilling.

Instead of grilling, I’ll be broiling this mu bing in glass bakeware coated with aluminum foil. This is a more convenient method of cooking in case your sun is just refusing to shine. It also make for moister meat, and since I’m making Chiang Mai-style mu bing, I want the pork to be fatty, juicy, and slathered in marinade.

Put the pork and marinade into the pan, and spread the meat evenly. This gets a little messy, so make sure your hands are washed and that you’ve got plenty of paper towels in reach.

After this is done, sprinkle three tablespoons of cornstarch over the pork and mix it in. This serves to thicken the marinade and make it stick to the meat. Six tablespoons of flour will also do. Many claim that flour has a sort of starchy taste in comparison to cornstarch. However, I’ve never noticed any real taste difference when it comes to this recipe.

Broil the pork for five to six minutes. You can go longer if you prefer tougher meat and more crispiness to the fat. The best time to prepare the lime chili dipping sauce is now, while the meat’s in the oven and the timer’s been set.

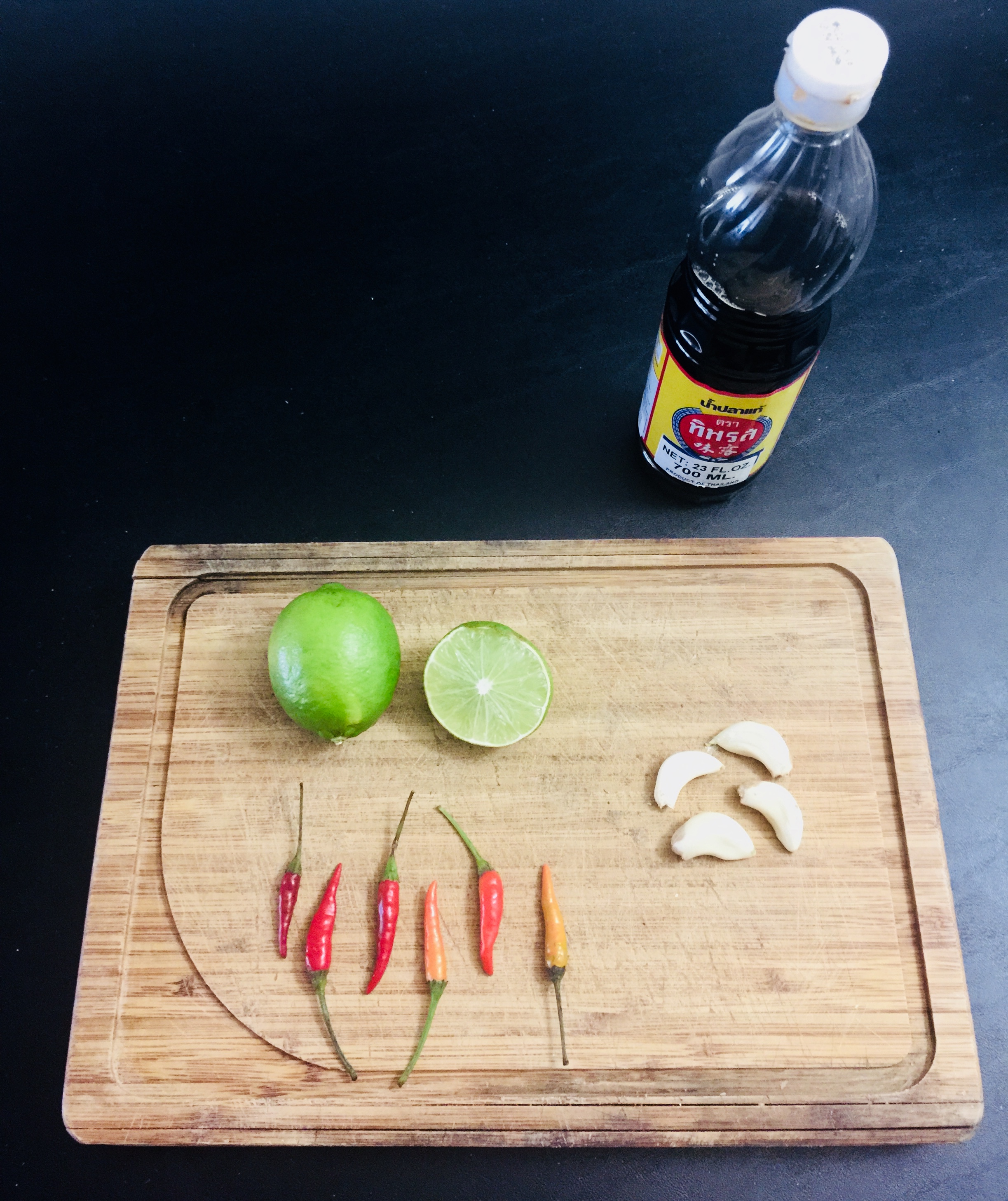

The dipping sauce is a simple combination of four powerful elements: sour (lime), spicy (Thai bird chili peppers), salty (fish sauce), and—garlicky (you know).

Mince the Thai bird chili peppers and garlic, and cut the limes however you like.

The actual recipe for lime chili dipping sauce is very loose. Instead of being guided solely by the recipe, your tongue should determine how much of which ingredient should be included. There are only a few rules you should follow (for optimal results):

1. Add equal parts chili peppers and garlic.

2. Add equal parts lime and fish sauce.

3. Add more lime and fish sauce than chili peppers and garlic.

Simple, right?

If you find the taste to be too strong, add a little water to dilute the sauce. Adding too much will kill the lime and fish sauce, so you’ll want to avoid that. Add a tablespoon of water and taste after each in order until you are satisfied with the taste.

The point of the lime chili dipping sauce is to add a little “pow!” to the mu bing. When dipping with sticky rice and mu bing, just a dab is okay. If you’re the type that rolls around your food in the sauce dish, or lets the food sit and soak, you may get more “pow!” than you asked for, and not much marinade.

At this point, the mu bing should be done. I broiled for five minutes—just enough for the fat to sear a little and for the pork shoulder to develop texture.

I recommend serving the mu bing with fresh cucumber slices and sticky rice. Since sticky rice is difficult to work with without the proper utensils, consider jasmine rice (you’ll use fork and spoon instead of your fingers). It can get a little messy eating, but this dish is so good you’ll be licking your fingers clean.