Slavery in Alabama

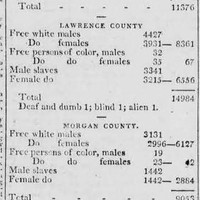

Like the other slave states, Alabama's ruling class was deeply reliant on the exploitation of enslaved people. During the antebellum period, the voices of enslaved people were generally not present in Alabama's newspapers. While news items like sale or so-called "runaway" notices were written by enslavers and the people who worked to preserve slavery, these articles nevertheless provide important insight into enslaved people's lives. For example, while runaway notices were designed as a tool of oppression, we can find in them evidence of people's attempts to liberate themselves or, at the very least, resist the institution of slavery by withdrawing their unpaid labor for periods of time.

Birmingham's Political Cartoons

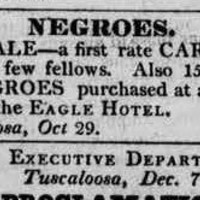

At the turn of the twentieth century, Birmingham rapidly emerged as one of the most important industrial centers in the world. The city developed around deposits of iron ore and coal, and became the largest producer of steel in the United States. The rapid development of Birmingham occurred during a time in the United States' history now known as the Progressive Era, where realities of urban development caused an interventionist spirit among the American public. In this context, the Birmingham Age-Herald often ran front page political cartoons that reflected the attitudes of the Progressive Era, as well as acting as a mouthpiece for Alabama's Democratic party and a booster for city development.

Building Black Communities After Reconstruction

In the wake of the Civil War, Black Southerners established permanent communities with independent economic, social, and religious institutions. During the period of Reconstruction (1865-1874), Black Alabamians were able to exert their rights both politically and economically. After Reconstruction ended, the withdrawal of federal troops left Black Alabamians without much political recourse as white Democrats slowly reconsolidated power through voter fraud and racial terrorism. However, even within this context, Black communities continued to grow and thrive, with civic leaders establishing schools, churches, businesses, colleges and universities, and vocational academies. In 1879, former schoolteacher and principal Charles Hendley became editor of the Huntsville Gazette. The Gazette, which ran from November 1879 through 1894, was one of two Republican newspapers in Huntsville at the time, and one of the most prominent Black newspapers in Alabama. Articles from the Gazette povide insight into the lives of Black Alabamians who strived to create enduring institutions and promote social uplift at the end of the nineteenth century.

The Constitution of 1901

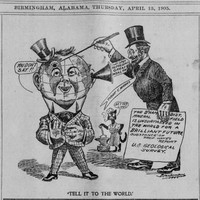

In 1874, following the end of Reconstruction in Alabama, the Democratic Party regained control of the state government. The subsequent Constitution of 1875, which replaced the Reconstruction Constitution of 1868, was the first attempt to strip Black Alabamians of their voting rights via the introduction of a poll tax. Between 1875 and 1901, the Populist movement spread in the South, threatening the dominance of the Democratic Party. Of particular concern to Democrats was the possibility of a biracial coalition of workers. To curb the threat of a unified working class, and permanently cement white supremacy into law, Alabama's legislature called a constitutional convention in 1901. The all-white delegation produced the Constitution of 1901. The document all but eliminated voting rights for Black and most poor white Alabamians, imposing a poll tax, literacy tests, employment requirements, and disqualifying voters convicted of minor offenses.

Women's Suffrage in Alabama

Alabama women had been involved in the suffrage movement since the 1860s. The beginning of the twentieth century, however, saw renewed and aggressive national activism for women's rights. In the context of the social concerns of the Progressive era, as well as third-wave of the temperance movement, some of Alabama's most prominent women formed the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) in 1912. Support for suffrage was not universal among women, however, with other prominent white women forming organizations to fight against women receiving the right to vote.

Labor Relations in Alabama

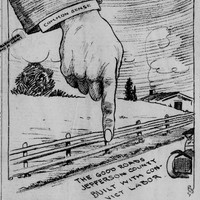

After the elimination of the slave labor system, the American South attempted to modernize and industrialize. At the end of the 1800s and into the twentieth century, Alabama's key non-agricultural industries were textiles, iron and steel production, and coal mining. While the wage labor system that supplanted slavery was a drastic improvement, especially for Black Alabamians, Alabama's working class still struggled with poor living and working conditions. Industrial labor was particularly dangerous and wages low. Consequently, Alabama workers often organized, forming interracial coalitions that participated in collective action. Their success, however, was limited.