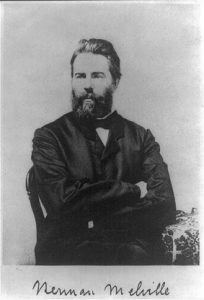

Herman Melville

1819-1891

Widely known as the “man who lived among the cannibals,” Herman Melville was one of the most famous Dark Romantic writers of the 19th century. As was typical of the Dark Romantics, Melville often criticized Reform writers from the earlier part of the century. Melville still believed that change was needed in American culture, and he viewed America at the time in a much more pessimistic manner than the Reform writers and Transcendentalists. Though he wasn’t as staunch of an activist as many of the Reform writers we have studied, Melville portrayed characters defying authority in some of his most famous works, including Moby Dick and Bartleby the Scrivener. This manner of writing did not sit well with a lot of people at the time, so Melville received a lot of criticism toward his works when they were first published. Nevertheless, Melville eventually rose to fame with his calls for social reform and creative writing style despite his often cynical attitude.

While the Transcendentalists often wrote of our American identity with a very optimistic tone, Melville wrote with the purpose of giving readers more of a reality check. In Bartleby the Scrivener, Melville targets our nation’s capitalistic system and authority. He does this by presenting readers with the interesting character of Bartleby, a disobedient scrivener on Wall Street. Whenever Bartleby’s boss asks him to do something, he simply responds with, “I would prefer not to,” showing no sense of concern to potentially being fired from his job (1490). This defiance displays a common theme in Dark Romantic writing of the shunning of civilization. It is considered the ‘norm’ in our society for an employee to respect the authority of his or her boss. By breaking this norm, Bartleby is breaking away from society in a sense, something Herman Melville was very passionate about as a Dark Romantic writer.

At the same time, Bartleby’s defiance shocks the narrator of Bartleby the Scrivener. He cannot comprehend how someone could have no regard to the possible consequences to his or her disobedient actions in the workplace, and he does not really know how to address the issue. As readers, we see the narrator weigh out the options in his head as to how he should proceed. Eventually, he decides to take pity on Bartleby viewing him as a lesser person. In this case, the narrator views himself as a philanthropist. Melville was skeptical of what motivated charity and philanthropy in a person, and he shows firsthand how it can lead to disaster as it did so at the ending of Bartleby the Scrivener.

Setting in Melville’s works plays an important part in the development of the plot, and the importance of setting is particularly noticeable in Bartleby the Scrivener. The narrator describes how Bartleby’s desk was placed in a space which had “a lateral view of certain grimy back-yards and bricks, but which, owing to subsequent erections, commanded at present no view at all…” (1489). In addition to creating a dark and ominous atmosphere typical in Dark Romantic writing, Melville shows how working in an office setting that is closed off from the world can potentially be problematic. This sense of isolation also reinforces the idea of the Iron Cage. In this case, the Iron Cage is used to limit distraction in the workplace and optimize production, two goals of any company in a capitalistic society. The fact that this story occurs on Wall Street, America’s center of capitalism, further displays Melville’s issue with our capitalistic society.

With his death at the end of the story, Bartleby becomes a martyr in a sense. His fight against the ideals of capitalistic America including hard work and respect for authority is eventually lost. By killing off Bartleby, Melville displays that the American system failed Bartleby and it is not as flawless as we imagine it to be. With his writing, Herman Melville gave America the sort of reality check it needed at the time.

Works Consulted

Melville, Herman. “Bartleby the Scrivener.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature: 1820-1865, edited by Nina Baym and Robert S. Levine, W.W. Norton & Company, 2012, pp. 1483-1509.