Early Life

Andrew Walter Crowley was a Marine Corporal in the First Reconnaissance Battalion who served in Vietnam from August 1966 to September 1968. Born on March 5th, 1946 in Medford, Massachusetts, Andy was raised in a traditional baby-boom household, attending catholic grammar and high school and worked a paper route and at a car wash. He admired his mother, whom he recognized as a saint, while his relationship with his father was less then wholesome. Andy joked that the only things in common the two had was their love of Ted Williams and their hatred for each other. While in high school, Andy worked at Elm Farms Grocery in Malden Massachusetts. There Andy recalled having the “ Luckiest breaks of my life because I met my life long friends there.” After attempting to work at a local mattress factory and attending Salem State University for a semester in 1965, Andy put in for a job at the Boston Gas Company, under his fathers guidance.

Vietnam

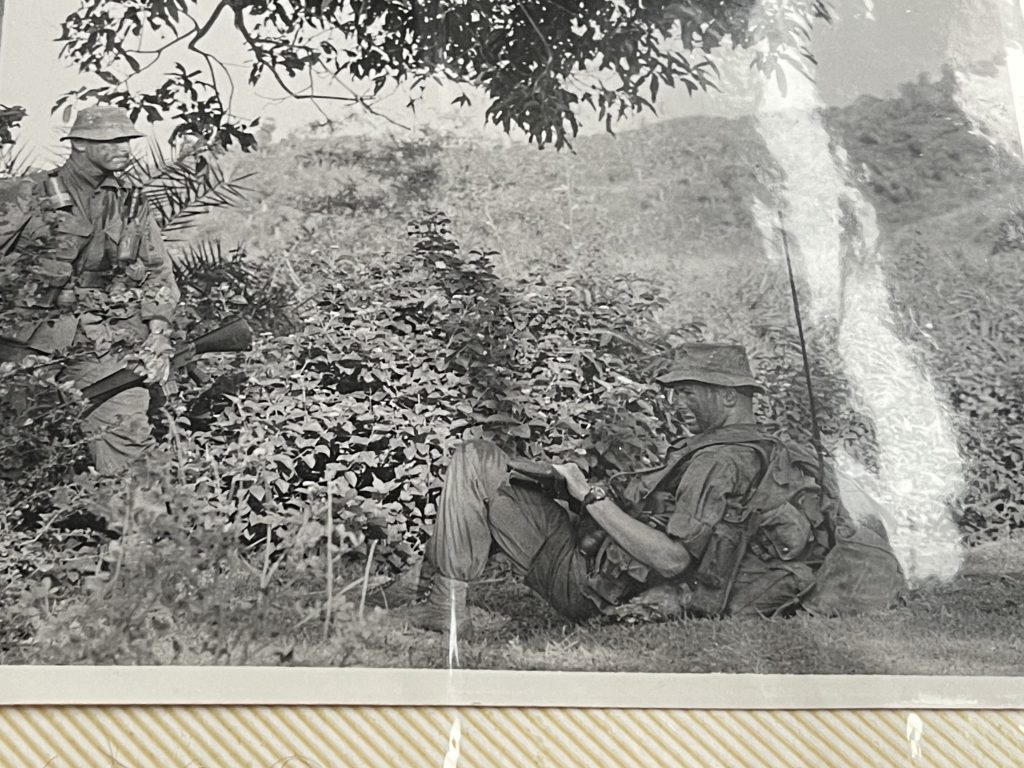

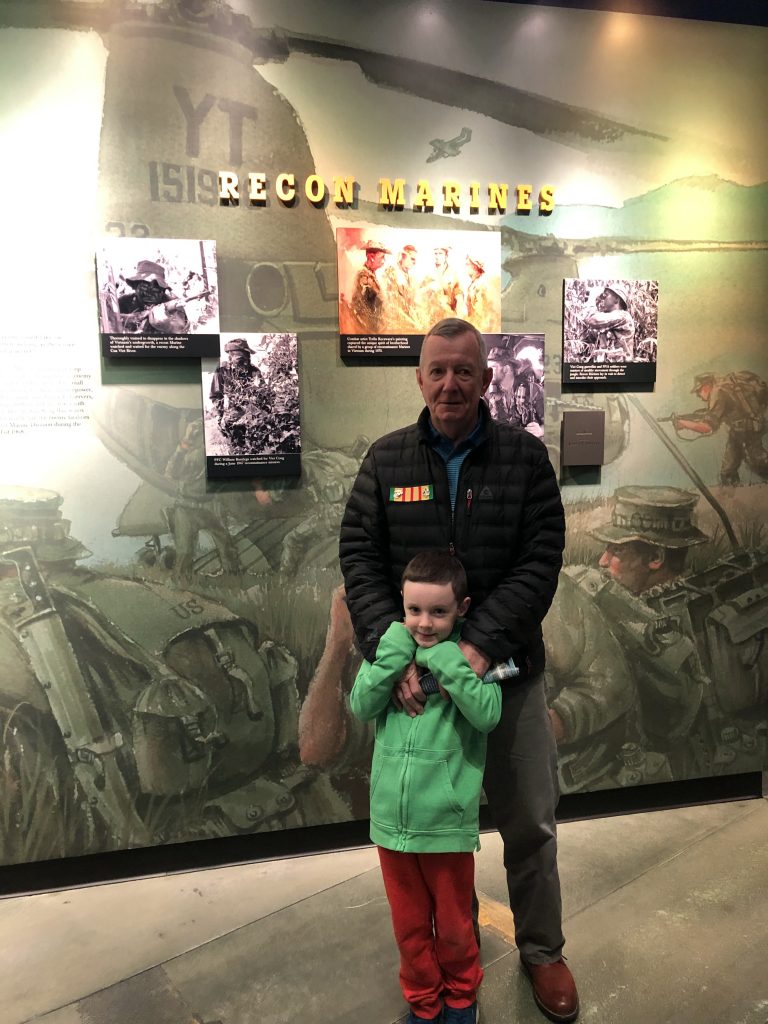

Andy enlisted into the Marine Corps and began training in August of 1966. Andy’s initial motivation to enlist in the Marines was through the television, watching the initial stages of the war through the news. After putting in six months at the gas company, Andy was also able to retain his job after his service and his time spent in the Marines would carry over for his tenure at the company, a patriotic luxury that many coming home from Vietnam did not share. Unemployment for veterans after was bleak for veterans returning home, as reported by the New York Times in 1971 “The Labor Department re ports that an average of 375,000 Vietnam veterans were unemployed during the first quarter of this year. A year earlier the number stood at 200,000.” After tough months of training at Parris Island and in California and Okinawa, Andy was assigned as a 30-11 infantry rifleman and landed in Da Nang on January 26th, 1967. Upon arrival at Da Nang, while not knowing a soul, Andy was recruited to join the first Marine Recon Battalion. Andy and five other men joined the first marine recon battalion due to a need for more men. In the Recon Battalion, Andy’s platoon was dropped into remote locations by helicopter in order to locate and report North Vietnamese positions. Their objective wasn’t to engage in action with enemy forces but they would occasionally set up ambushes, as their Moto was “swift, silent, and deadly.” These small numbered platoons would go out in the middle of nowhere for several days at a time.

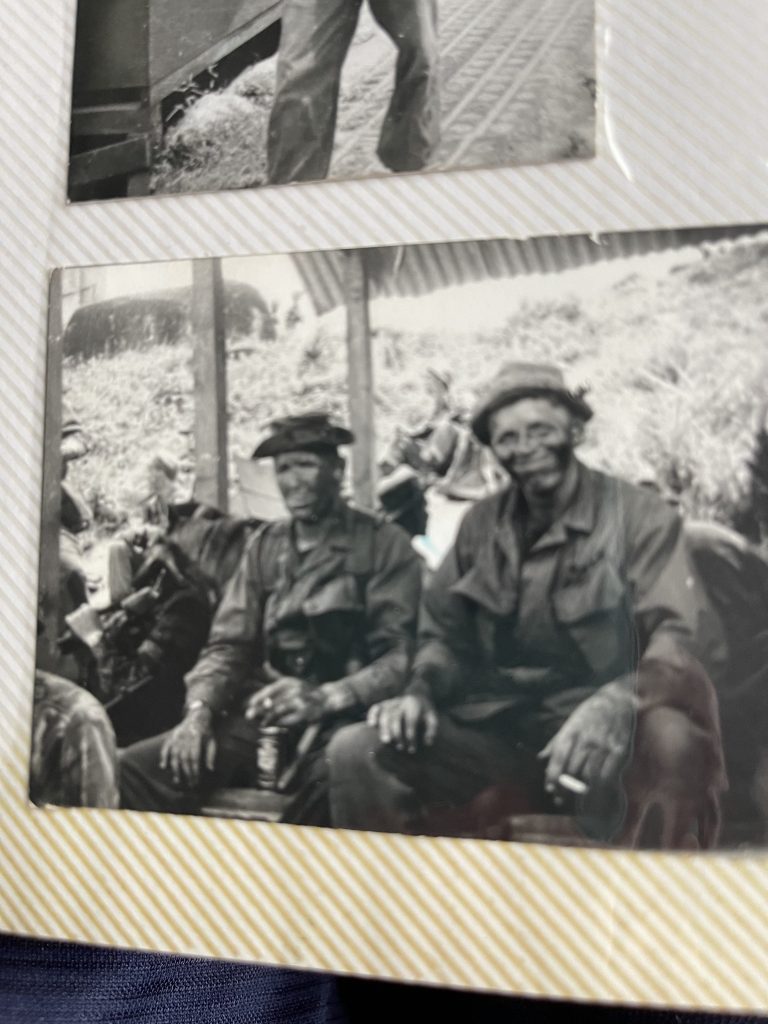

Joining the recon battalion gave Andy a better chance of survival, as he recalled that some marine riflemen would spend up to sixty days at a time out in the jungle. Much of what kept Andy grounded through his time in Vietnam was the simple goal of surviving. He refrained from using the term hero, rather he would call himself a survivor of the war, stating in our interview “it was like your job, you know, I didn’t wish I was somewhere else or, you know, I just, day by day, you know.”

Andy’s tour was originally supposed to last thirteen months, but he was sent home after a year on January 26th, 1968 (Four days before the first phase of the Tet Offensive). Andy spent thirty days back home, which he said was almost as hard as his time in the military. Shortly after returning, he learned of the death of one of his close friends John Waydn. Despite the hardships that he had endured during his time over in Vietnam, Andy chose to extend his service after a month back home, saying the bonds built between his fellow marines was more important than any relationship he had in the states at the time.

“I extended for six months because I wanted to stay with my guys. I became a patrol leader then too, for the last six months, I was, I led the teams going out, and, that, that was, they were my family. They were more family than my own family. We lived together, you know what I’m saying? 24 hours a day, seven times, seven days a week, we went out in the bush together. We drank together when we’re back in, we lived together, we fought, we, you know, had fun, we did everything but they were family. And when it came time, I had a year and a half to go. I said, what am I gonna do back there? You know, let me stay here when I’m making a difference,”

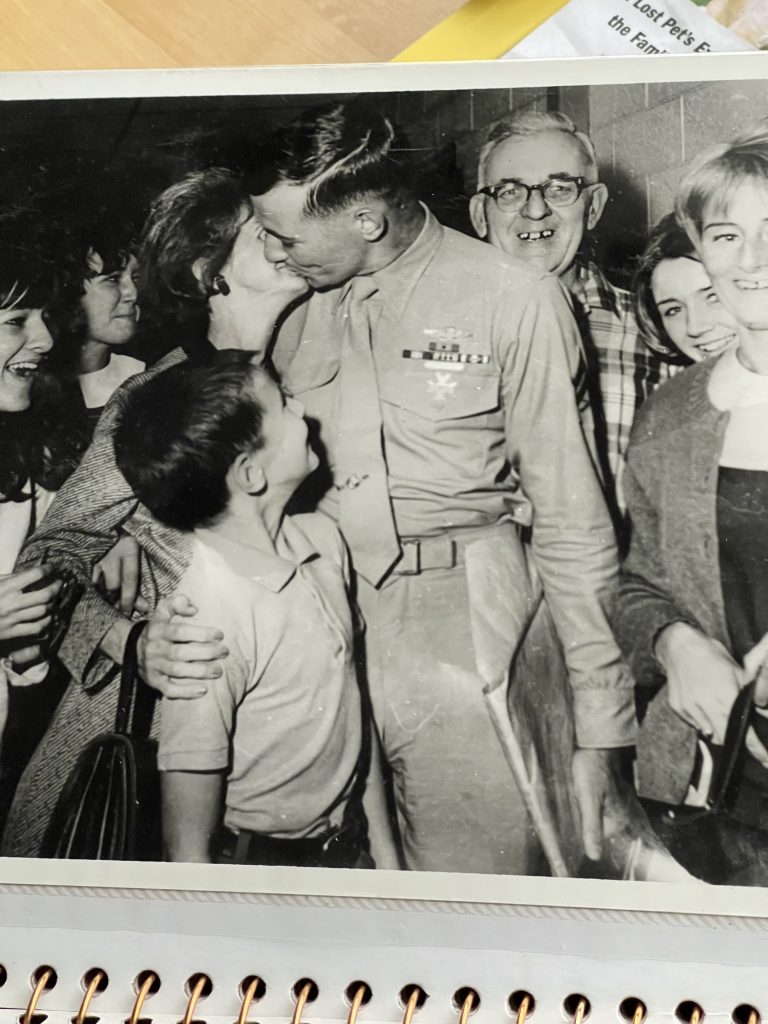

He left Vietnam as a patrol leader on September 26th, 1968 and was dismissed from the military shortly after. After returning home, Andy returned to the gas company where he would remain for the remainder of his career, retiring to Plymouth, Massachusetts with his wife in 2015.

Memorable Experiences

Andy was open to sharing some of his most memorable and difficult memories. On one patrol while Andy was a radio operator, when the group stopped for a break, one of Andy’s good friends Pete Camytic was shot in the head and died in Andys arms. Through monsoon like conditions, Andy’s platoon went down a hill being chased by VietCong guerrilla fighters, all while Andy and his lieutenant were carrying the body of Pete. Andy had to make the tough decision of leaving Pete’s body at the hill in order to rescue the rest of the platoon. After a helicopter was able to pick up the remaining men and bring them to safety, Andy broke down in tears, but it was a decision that he didn’t regret. As he remarked “if we don’t, there’s a good chance we’ll all lined up dead. It was really my call to do that. Andrew. And I never regretted it because if I was ever where Pete was, I would say to them, leave me here and get the hell out of here. I’m dead. There’s no bringing me back” When I asked him later in the interview if he ever had or considered traveling back to Vietnam, Andy recalled he would have only to see if he could recover Pete’s body.

Another story Andy shared in our interview was his most memorable moment of the war while on patrol at Charlie Ridge, one of the most active parts of the war that usually resulted in contact. After sighting an enemy on a trail and exchanging gunfire, Andy went down to a large bomb crater to investigate. There he found a Vietnamese person pop out of a bush and “with his thumb in his ears and waving his fingers at me like making a face.” This alarmed Andy and reminded him of his friend John Waydn. Andy had learned while on leave at home that John and his platoon were lured into an ambush and were brutally dismembered. After alerting his lieutenant of the situation, Andy’s platoon set in for the night. The men hid low in brush and heard a large group of VC looking for Andy’s platoon. Andy in the interview credits John for saving the platoon then, but were it not for Andy’s knowledge of the situation and his quick intuition, Andy’s platoon could have met a similar fate like his friend, meaning Andy saved the lives of all of those men.

Interview Analysis

Andy went into the war with the spirit of enlistment that his fathers generation had had during World War II. Many of the friends he had grown up with joined together as he remarked in the interview “I started the gas company in February of 66, and we all hung around this, the Strand Cafe. It was a bar room right down the street. All the meet the phone guys, the gas guys, the electric guys. We all hung around there and the bartender was the marine recruiter.” Andy and his friends also thought highly of the power of the US Military, and that its massive arsenal of weapons and infantry would overpower a small country like Vietnam, and many believed they wouldn’t be there for long.

During the interview, Andy shared compassion and understanding for the people and the soldiers of Vietnam. The VC’s determination and purpose was seen by Andy and his fellow marines, the more resistance they met the more they came to understand their unbreakable will. Andy came to the realization that the US did not need to remain in Vietnam and though dragging out the war was a terrible thing to do. He held the highest respect for his enemies. Once while visiting the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC, he was approached by a Vietnamese guide. After helping Andy locate the name of one of the men in his outfit, they emotionally embraced and hugged each other despite being complete strangers. “They were fighting for their country.” he stated in the interview “and we weren’t.”

Andy also shared sympathy for those veterans who faced backlash from the Anti War movement. Andy attributes the progressive, middle class environment of Medford, Massachusetts for the reason he didn’t face much of the poor treatment to veterans. Despite feeling sorry for the veterans that did, he understood why the protesters of the war reacted the way they did and he didn’t have any strong opinions on the matter, stating

“There was a lot of people, you know, that love, they make themselves feel better about themselves when they criticize somebody else, and I think there was a lot of that because there was no defense, you know, baby killer, whatever you wanna call, you know. And, uh, so, you know, I, I try to see that some of them, it, it, somebody that goes to Canada, boy, they disrupted their life when, for whatever reason, if they were scared, if they were against the war, hey, they’re paying a price for what they feel.”

Andy’s strong negative opinions about the war lay more with the officials and politicians that affected the war. Names like Nixon and Kissinger, who he had shared contempt over due to the bombing campaigns against Cambodia, were who he blamed for prolonging the war and failing to address the moral and strategic issues the war caused. In the interview, I asked him what he thought was the most significant impact the war made to American society that he’s witnessed in the fifty years since his deployment. He recalled the shift in attitude towards the military and the disrespect it received after Vietnam. When he enlisted, there was still a belief that fighting for the military was always for a just cause, once he got out no one wanted to enter the military, the war had killed the spirit of enlistment into the military. Numbers back up Andys opinion, it is reported that “The connection between society and the military is being lost. With only 2.2 million personnel, both the active and reserve components combined comprise less than 0.7 percent of the population.” (Treanor) His conclusion was “the Vietnam War caused an absolute terrible image of the military, not so much for the individual, but as a group, you know, as you know, what did we ever do this far? You know, we, we never should have done this.”

Transcript

file:///Users/agarvin01/Downloads/OralHistoryTranscript.htmlReferences

First Force Reconnaissance Company https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/1st-force-reconnaissance-company/

After Vietnam, American Society’s Relationship…. https://mwi.westpoint.edu/after-vietnam-american-societys-relationship-with-its-military-was-badly-frayed-after-twenty-years-of-post-9-11-wars-it-is-again/#:~:text=After%20Vietnam%2C%20American%20Society’s%20Relationship,%2D%20Modern%20War%20Institute

Job Outlook Is Bleak for Vietnam Veterans https://www.nytimes.com/1971/06/05/archives/job-outlook-is-bleak-for-vietnam-veterans-vietnam-veterans-job.html