Interview Summary

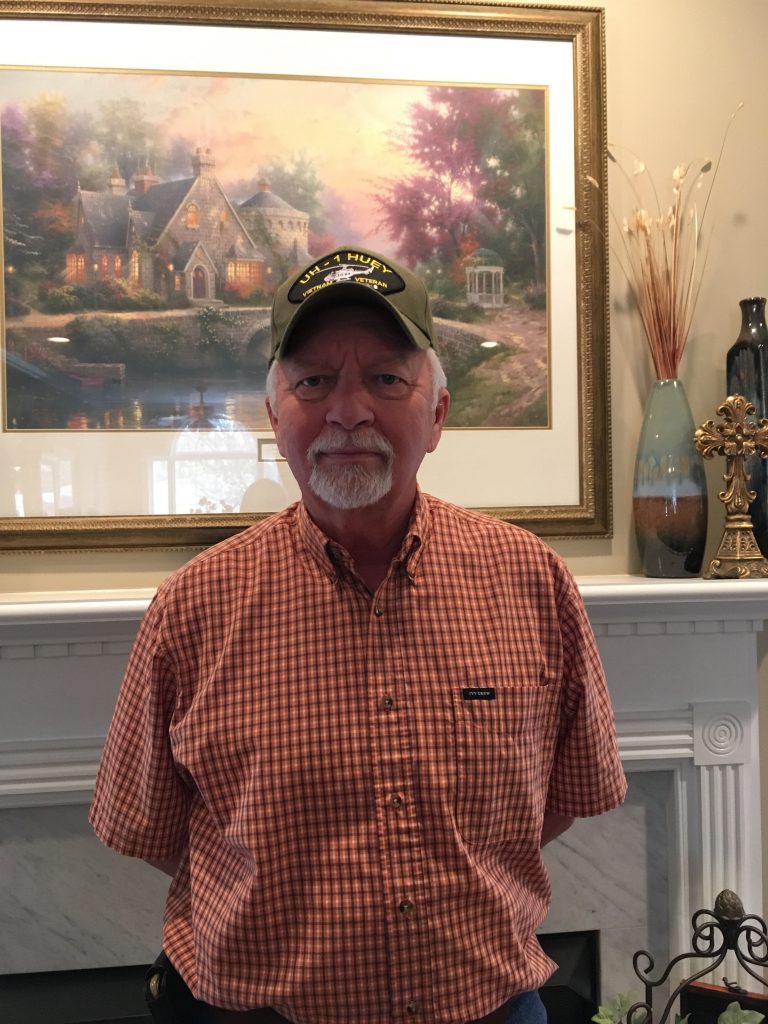

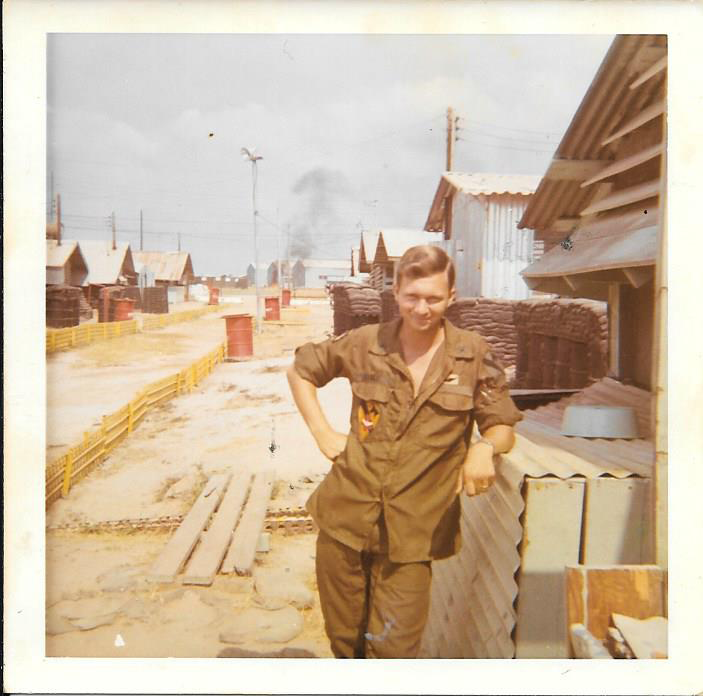

Clarence Sims was born on November 23, 1950 in Sylacauga, Alabama. Growing up, his family did not have a strong military background. Since his family did not have much of a military history, Mr. Sims was not planning on enlisting in Vietnam. That changed when he received his draft notice in November 1970. My interviewee discussed his time serving in An Loc, Vietnam, agent orange repercussions, and his experience after returning to the U.S. He received his draft notice in November 1970. He reported to the Bessemer draft board and thought he would return home that evening. He left directly from the board and went to Fort Polk in Louisana. He did not get to tell his wife or family goodbye and did not come home for 2 weeks. After he completed his basic training, he and his wife moved to Fort Eustis, Virginia. He was then sent to Vietnam to Camp Eagle and was in the 101st Airborne. Mr. Sims was a crew chief on a Huey helicopter. He spent most of his time in Vietnam as a medevac picking up and helping the wounded. When he left for Vietnam his wife was five months pregnant. His daughter was born while he was in Vietnam and he did not find out for a few days after her birth. He saw his daughter for the first time when she was eight months old. After returning home, he was not given any information on his veterans’ benefits.

Life Post-Vietnam

“…they brought us home, dumped us on the street, and were supposed to be normal again. We weren’t normal…”

Clarence Sims on life after Vietnam

He came back to the U.S. after serving one year in Vietnam. He returned to the U.S. in Oakland, California. Mr. Sims said, “those people there were pretty rude. Here, just went back to the normal way of life. I mean, they brought us home, dumped us on the street, and were supposed to be normal again. We weren’t normal, no”.

He was not informed about his benefits, including the VA. He did not start going to the VA until he retired in 2001 after a friend told him about it. He returned back to his job at U.S. Steel immediately after returning home. He often worked overtime at U.S Steel along with another job so that kept his mind busy. At that time, he did not struggle with PTSD and nightmares as bad as he would eventually. However, he does think if he had talked to a doctor directly after returning, he would have been diagnosed with PTSD. After he retired, his mind was not as busy and this allowed him to think about his experience in Vietnam. He started waking up with nightmares and experiencing PTSD more. He talked to a doctor and they recommended medication, however, he did not want to use medication to fix his PTSD. He leaned on his faith to help him and he said it did get better.

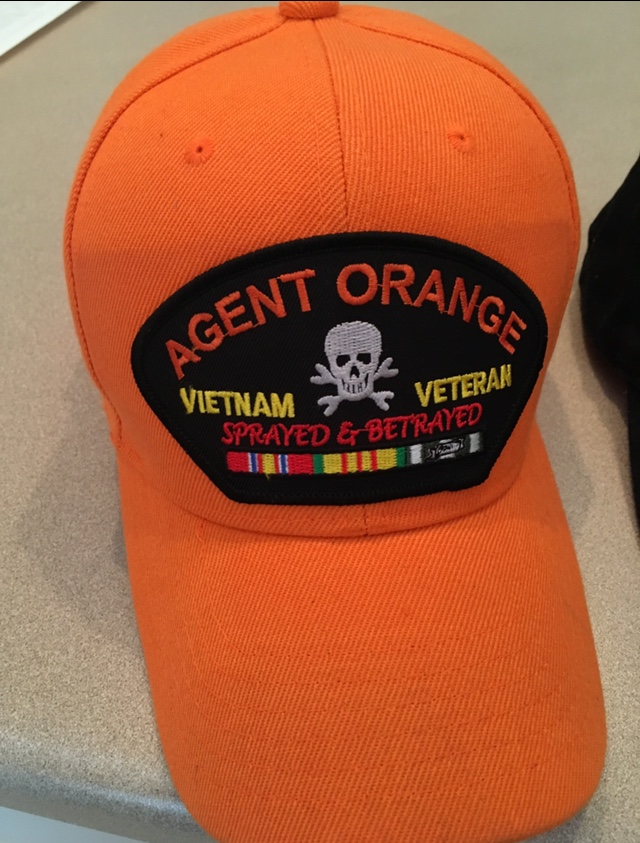

Agent Orange

Mr. Sims had health issues related to his exposure to Agent Orange. He has ischemic heart disease and neuropathy in his feet as well. The VA never informed him he could potentially have health issues because of Agent Orange. When Mr. Sims arrived back in the U.S. he was not given any information on what his benefits were or how to access them. He did not know about Agent Orange until after his brother-in-law passed away from Agent Orange exposure. His sister helped him go through the screening process. About 8 weeks after he was screened for Agent Orange he was classified as a disabled veteran.

Agent Orange and Life Returning to the Homefront Research

Agent Orange was sprayed across South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia to clear jungles and destroy enemy crops. Around 12 million gallons of Agent Orange was used on Vietnam alone killed about 5 million acres of forest. At the time of the war, Vietnamese doctors reported babies being stillborn will birth defects. However, the United States dismissed these claims as untrue and enemy propaganda. Despite Korean and Vietnamese veterans believing that Agent Orange was responsible for their health issues, the U.S. insisted it was safe (Reagan 1). Even though military members reported health complications potentially related to Agent Orange exposure as early as the 1970s, there has not been much research done on the issue. One of the issues Clarence Sims has experienced has been Ischemic heart disease. According to a study done by the American Journal of Public Health, Ischemic heart disease is one of the more common diseases associated with Agent Orange exposure (Stellman 1-4).

Commander Peter Langenus discovered after returning home that veteran benefits for those returning home, “were almost nonexistent” (Ciampaglia). Professor Christian Appy from the University of Massachusetts Amherst said that society and the government was not prepared to give the veterans the benefits they deserved. Mr. Sims discussed having issues returning back to society and being normal. He also expressed that he did not have the support he needed from the government he needed when it came to information about his benefits. Appy said they were looking for “basic human support and help in readjusting to civilian life after this really brutal war” (Ciampaglia).

“I really hope your generation don’t have to go through any of it… It is not pretty. A war.”

Clarence Sims on what he wants people from my generation to know.

Clarence Sims standing outside his Huey helicopter

Jungle in Vietnam

A helicopter flying in Vietnam

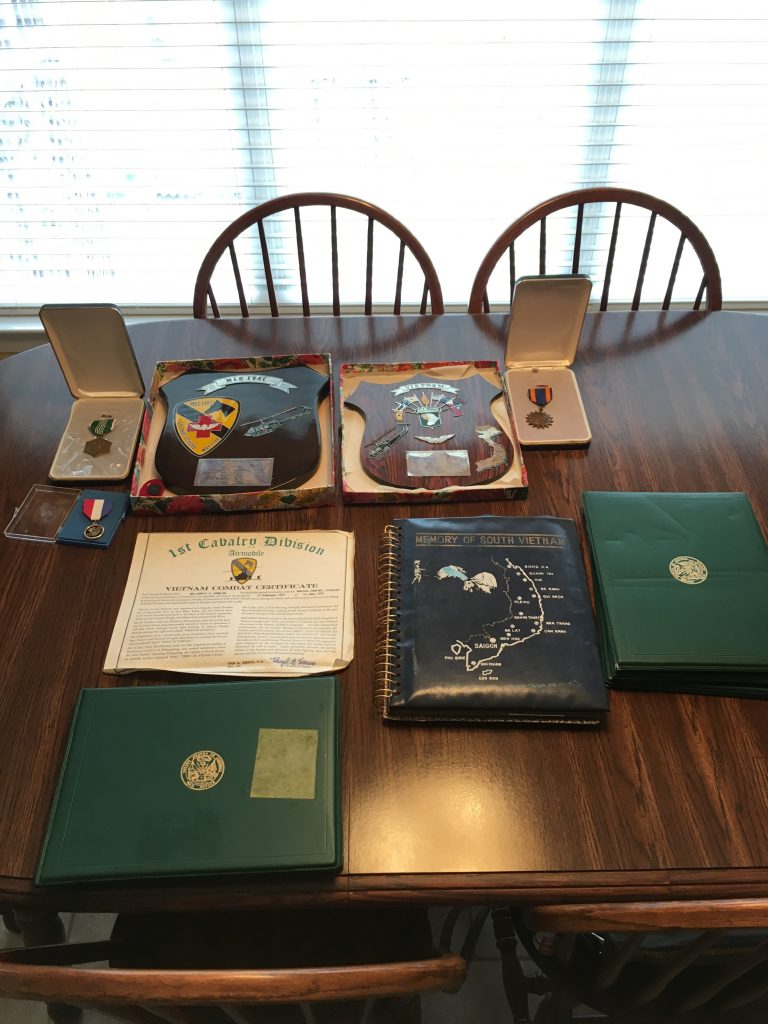

Medals, accolades, and a photo album

Med Evac shield

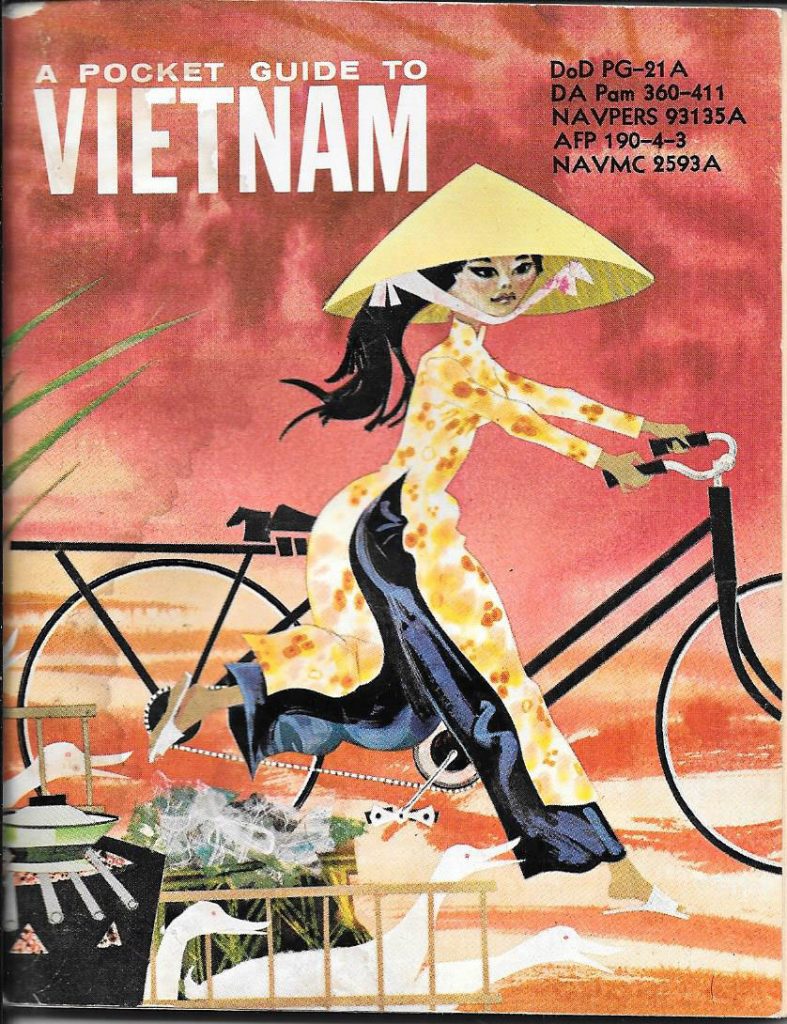

A brochure given to military members to inform them about the Vietnamese culture

Transcript

Interview Audio

Additional Readings

Ciampaglia, Dante A. “Why Were Vietnam War Vets Treated Poorly When They Returned?” History.com. November 08, 2018. Accessed May 02, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/vietnam-war-veterans-treatment.

Reagan, Leslie J. “‘My Daughter Was Genetically Drafted with Me’: US-Vietnam War Veterans, Disabilities and Gender.” Gender & History 28, no. 3 (November 2016): 833–53. doi:10.1111/1468-0424.12252.

Stellman, Jeanne Mager, and Steven D. Stellman. 2018. “Agent Orange During the Vietnam War: The Lingering Issue of Its Civilian and Military Health Impact.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (6): 726–28. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304426.