Path to Vietnam:

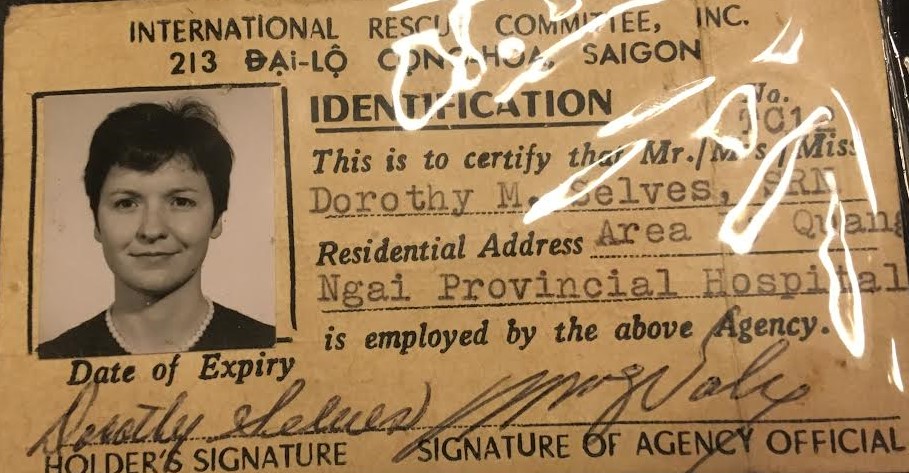

Dorothy Peacock was born in 1936 in Ontario, Canada about fifty miles from Lake Erie. She grew up on a subsistence farm with her family before attending nursing school in Stratford, Ontario. Dorothy Peacock trained in anesthesia in Toronto and was working at Kaiser Hospital in Portland, Oregon when she came across an ad in the British Medical Journal for an anesthesiologist to assist in cleft palate repairs in the “win the hearts and minds” program in Vietnam. She describes her path to Vietnam as a “casual thing to do with not very serious interest,” but it became serious quickly because the International Rescue Committee (IRC) sponsoring the program contacted her three days after she answered the ad. Dorothy Peacock did not even bother putting her answer to the ad in an envelope and just put a stamp on a folded piece of yellow scratch paper, so she was surprised when the Washington D.C. office called her for an interview. At the interview, she was informed that a surgeon, Dr. Blanco, was already working at Quang Ngai, Vietnam and had lost patients because of inadequate airway management during surgery. IRC wanted to send her as soon as possible to assist Dr. Blanco, so she did not go through any training because she already knew how to do anesthesia. She later found out that other IRC workers trained in Hawaii to learn the culture and language before going to Vietnam, but she had to get there quickly because Dr. Blanco did not want to perform any more procedures without someone trained in anesthesia. Dorothy Peacock arrived in Quang Ngai in 1967 as a 29 year old with very little knowledge of the war or Southeast Asia.

“The choice to be there is very different mentally and emotionally than the solider who is conscripted and shot at. I was shot at too, but then I volunteered for that. It’s a world of difference”

On the first day Dorothy Peacock arrived in Quang Ngai, she questioned whether she had made the right decision to leave North America. Her plane had been shot at during the trip and her luggage was lost. She arrived at the hospital and met a wise nurse who put her fear in perspective by showing her three dying tetanus patients. The nurse said, “We have better ventilators here than we have at home. They never fail here”. The families of the patients had set up shifts to hand ventilate their sick relatives because there were no machines in Vietnam to do it for them. Dorothy Peacock knew she had left modern healthcare, so she quickly adapted to the conditions in Vietnam.

International Rescue Committee (IRC):

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) was founded in 1942 when the International Relief Association (IRA) and Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC) joined forces. The American IRA branch was founded at the suggestion of Albert Einstein to provide care to Germans suffering under Hitler while ERC was formed to aid European Refugees in Vichy, France. IRC functions to provide emergency relief programs, hospitals, children’s centers, and refugee resettlement projects. In 1954, IRC began a long-range relief and resettlement effort for Indochinese refugees including the Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians.

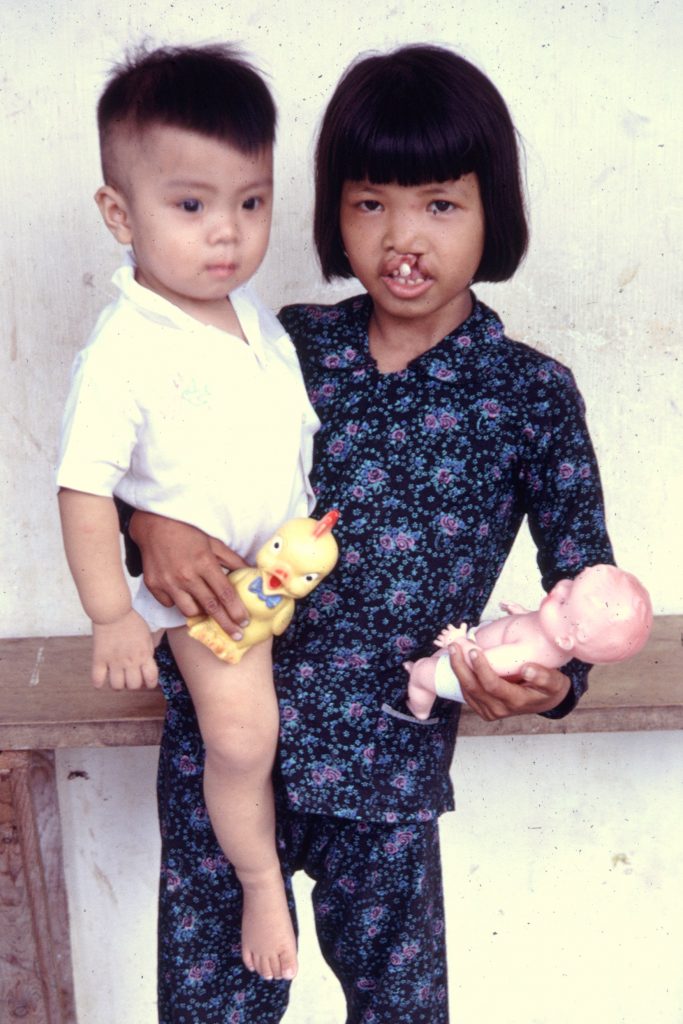

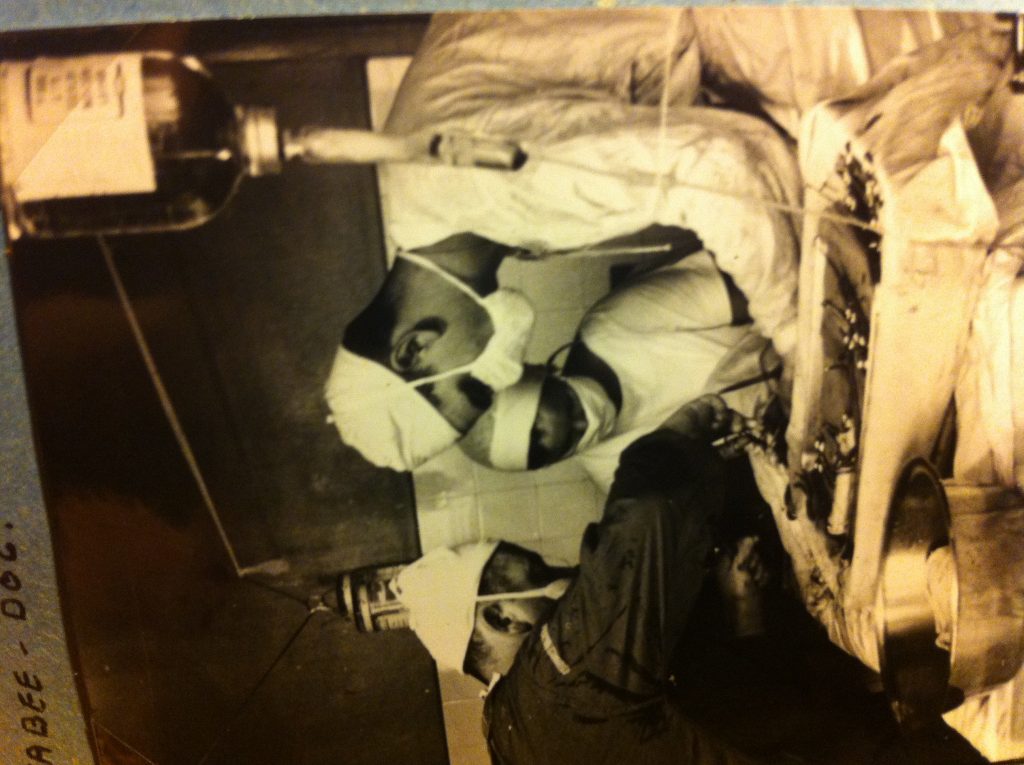

The “win the hearts and minds” program sponsored by IRC focused on the Vietnamese people and what could be done to help them. Dorothy Peacock said there was no attempt to gain the trust of the Vietnamese people because the “bamboo wire” relayed word that the IRC volunteers could be trusted. The team focused on cleft palate and lip repairs, along with vaginal fistula repair due to the lack of obstetrical care in Vietnam. A cleft palate repair would only take Dr. Blanco around 45 minutes, but it would dramatically change the patients’ lives who might have had trouble swallowing or were terribly disfigured before. Dorothy Peacock’s jobs during procedures included anesthesia, but more importantly-sharing the airway with the surgeon. She had nothing, but stellar comments and fond memories about her team. Most surgeons cannot work without their toys, but Dr. Blanco was an extremely functional and brilliant man while Cora was a “jack of all trades” with Irish humor and wit.

Dr. Blanco and Dorothy Peacock post-surgery

Healthcare in Vietnam:

The use of helicopters to evacuate the wounded had shown great success in Korea, so the Medical Department began to focus on developing new equipment to make this process more efficient and decrease mortality rates among the wounded. The Bell UH-IA “Hueys” replaced the Sikorsky H-I9Ds helicopter ambulance units in 1960. The Huey could carry two litters or five patients along with a flight crew of two, flight medic, and crew chief. The Hueys were known to pick up wounded American soldiers and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) soldiers, but they also began to rescue the injured Vietnamese people. Most soldiers were sent to Army hospitals, but the Vietnamese citizens would arrive to hospitals like the one Dorothy Peacock worked in at Quang Ngai. Patients would arrive either on foot, the French Vehicle, lambretta, hammocks made of bamboo, blankets, and fishing net, or by helicopter.

“It was seventeenth century in the front door and twentieth century in the back door”

The hospital in Quang Ngai was modeled after a French cottage hospital and included an orthopedic ward, general ward, and burn ward while the surgical ward was a two story building separated from the rest of the hospital. The size of the rooms were 50 feet by 70 feet with beds packed next to each other and an army litter on top of two beds. Patients would share beds with even more injured laying in the aisles. There was no privacy, HIPPA, private rooms, or cafeteria.

“Those beds are so close together that often you are moving one bed if you want to get to the head of the next patient on the other side”

There was lack of infrastructure with no clean water or sewage. During the summer, thermometers would explode in operating rooms because there was no air conditioning. During the rainy season, it was impossible to dry linens or surgical gowns because everything would stay damp. The hospital staff would wear gloves, but there was a lack of clean gowns, so they followed the rule of keeping their hands away from their face. All volunteers had penicillin and tetanus immunizations, but the Vietnamese did not. Round worms, malaria, staff infections, and infection was very common due to E. Coli contaminated water and lack of modern healthcare. Though there was anesthesia during surgery, there was no post operative pain medicine due to the lack of resources, but the Vietnamese never complained.

Escalation of the War: Tet Offensive:

As the war escalated, the Vietnamese population knew that there were no lip repairs some days because the IRC volunteers had to set up triage and assist with emergency surgeries. Helicopters would bring injured patients with penetrating stomachs and chest wounds from bullets and bombs. Dorothy Peacock remembers picking up a four year old boy in complete shock who had been playing and stepped on a landmine. The air blast fractured both femurs, but his upper body was fine. The team performed amputations and colostomies numerous times everyday.

Shrapnel from amputee patient

“Destroyed land”

Dorothy Peacock and Dr. Blanco mid-surgery

“We were making a country of unclosed colostomies and amputees”

On January 31, 1968, the North Vietnamese attacked more than 100 cities and outposts in South Vietnam and Quang Ngai was one of them. The hospital was protected by slit trenches and slit windows created with sandbags. The person inside could swivel the gun to the right and left while the attacker’s bullets had a small chance of hitting the shooter. Sandbags were used by many Vietnamese people to protect their households and children packed them constantly. There was so much shooting outside that the medical staff could not get to the hospital. For two days, everyone stayed inside and Dorothy Peacock did her best to assist with injured patients in the shelter. One woman who had just given birth was injured in a blast with a wound on her jaw and damaged the insertion of her tongue. Her arm was broken as well, so the woman made a sling for herself out of cloth to hold her tongue so she could breath while using her uninjured arm to let her newborn eat. Dorothy stitched her tongue to her chest because the jaw was gone, but the woman could not have been happier because the infant could suck from the other breast. At that point, Dorothy Peacock knew, “we can’t go home…we can’t go home”. Dorothy Peacock was given the option to leave right before the Tet Offensive because the government knew something major was about to happen. She signed a contract with IRC not the government, so she had more options to leave than the soldiers who would be named deserters if they left.

“The morgue in the hospital was shoulder height. A room 10 by 10 shoulder height with bodies….rigor mortise bodies and there was an American hand with a dog tag”

The team understood some patients could be Viet Cong, but Dorothy Peacock was surprised when she left one of her surgeries to get a curved connector for her patient and saw a man dead on the operating room table. It was undoubtedly a purposeful war, but it was one of the realities of war. She describes her experience in Vietnam as a schizophrenic time because she would eat one meal a day with soldiers who would share their war stories while other soldiers could not meet her eyes. She observed men who drank too much or gambled too much in an attempt to escape the war. “The sense of desperation….one could be aware of that” just looking at the men, but her experience was not like that. Unlike the soldiers, Dorothy Peacock had no specific orders or supervising officer, so she voluntarily reported the activities performed by the IRC volunteers. She saw the Vietnamese people as friends, coworkers, and victims of civil war while the soldiers had a different perception of them.

“It was a war of sandbags, barbed wire, and Huey helicopters”

The People of Vietnam:

“bright, clear-headed people”

“All is Well”

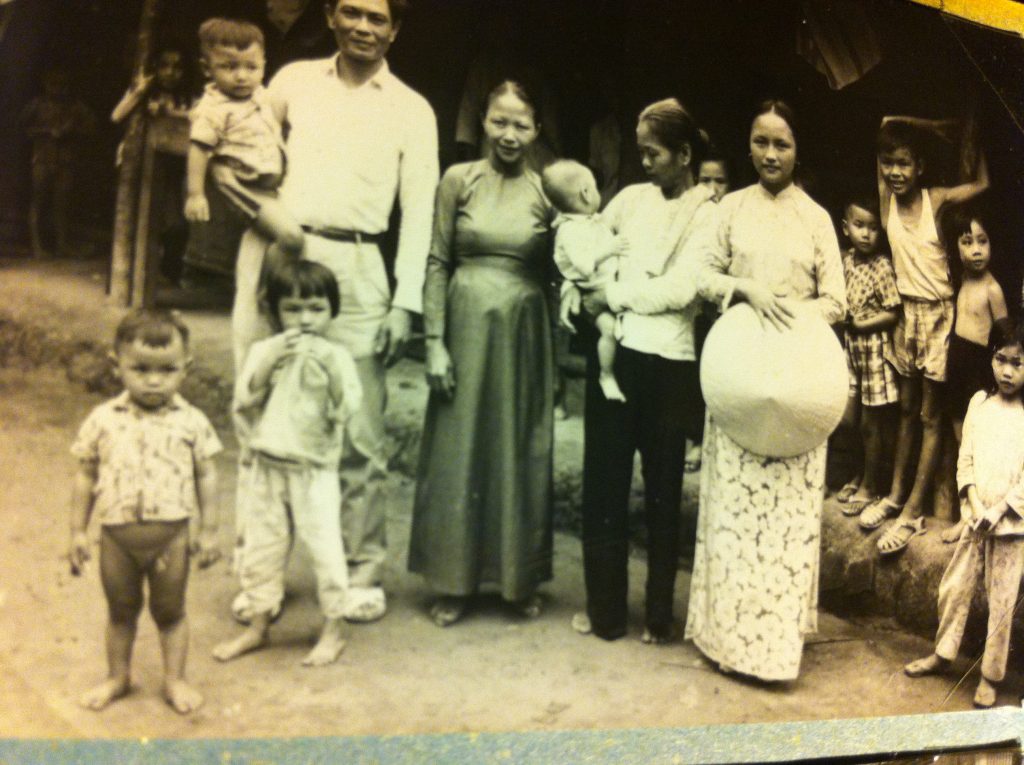

Vietnamese Maid wearing Ao Dai (right) with family

“I like to say that I looked at the milk of human kindness in Vietnam”

Dorothy Peacock integrated into Vietnamese society quickly and fell in love with its people and culture. The Vietnamese surgeons were mostly female because the men were fighting in the war and performed intense surgeries including amputations and emergency trauma surgeries. She described the Vietnamese people as intelligent, family orientated, dexterous, and hard working. She became close to the families of her Vietnamese coworkers and the family of her maid. She attended weddings, dinners, and church and wore the national costume, Ao Dais, along with the Vietnamese women. Dorothy began to understand the people and symbols of Vietnam. Children would bring the water buffalo home and as long as they were still performing that task, she knew that, “All’s well. God is in haven and all is well”. She described the Vietnamese people as extremely religious and the ones of Buddhist faith refused blood transfusions even if they could not survive the amount of blood loss. Accepting the blood would mean that there body would not be whole in the next life. The Vietnamese people were deeply attached to their ancestors lands and evacuating their homes because of the war was extremely difficult for them. Once Dorothy Peacock returned to the United States, she often remembered Quang Ngai and the strangers that became her family.

“You looked after one patient and that one patient was better for a minute anyway and you thought that your life counted”

Dorothy Peacock Post-Vietnam:

Dorothy Peacock returned from Vietnam in the Fall of 1968 and continued working as a nurse anesthetist. She followed the War closely and was shocked and horrified when the My Lai Massacre went public. My Lai was about 10 miles from Quang Ngai. When she looked back at letters and patient reports she had sent home, there was no influx of patients on March 16, 1968. She knew it was because the whole village had been killed. Dorothy Peacock has lived an adventurous life and is continuing to do so. She retired at 70 years old and is an active member of Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI), Tuscaloosa sailing club, and many other organizations in the community. She has also volunteered as a Nurse in Afghanistan and climbed Mountain Ranges all over the world including Mount Fuji and Mount Kilimanjaro.

Transcript and Audio:

Dorothy Peacock Recommendations:

– My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent Into Darkness Howard Jones

– Miss. Saigon: Bui Doi (Dust of Life) https://youtu.be/fdi8c70rE_4