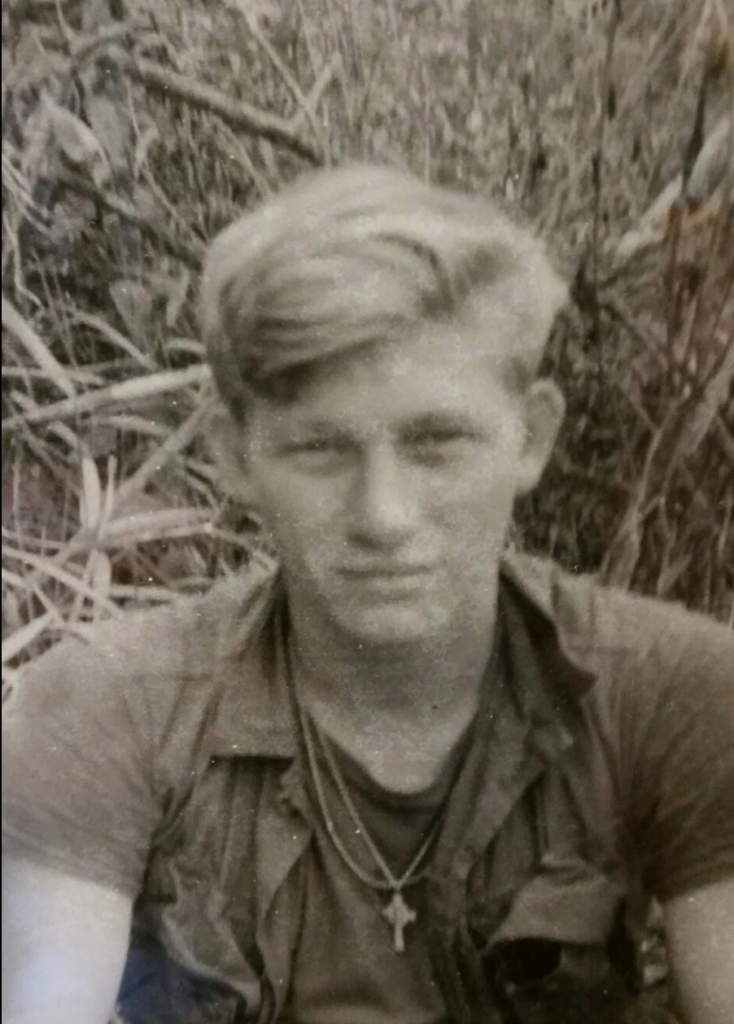

Doyle Ross is a U.S. Army Veteran who served in Vietnam.

Pre-Draft

Doyle Ross grew up in a small town in Boaz, Alabama. Doyle is also the younger brother of my grandfather, TJ Ross, who also served in the Army in Vietnam. After graduating high school and without plans to go to college, he started working in my grandfather’s vehicle body shop. However, after a recent call for an escalation in the number of troops sent to Vietnam, he had a gut feeling that he and my grandfather would both be drafted.

Draft and Basic Training

After Doyle’s draft number was selected, he made up his mind to go willingly and without any trouble. My grandfather was drafted at the same time, and Doyle had to convince him to stay and go. Training is an important part of being in the military, and I have often heard from those currently in the military that you do not use a lot of the skills you develop during training. However, in Vietnam, Doyle asserted that you had to use every last bit of your training while in Vietnam.

Touchdown in Vietnam

After Doyle first arrived in Vietnam, the first thing he noticed was how hot and humid it was in the country. At first he was not sure if he would be able to make it a year in Vietnam with how hot it was, but that after about two weeks he got use to it.

An interesting point is that normally when you think about the Vietnam War, most would assume it would be those who were drafted that would be the most upset by the time they reached Vietnam. However, Doyle recalls that the majority of those that you would see and hear crying would be the soldiers that had enlisted. Being scared played a role in soldiers deserting , however Doyle did not understand why some of the soldiers would attempt to desert.

When I pressed a little more about why many of the men that enlisted were crying upon reaching Vietnam, he stated that it was because most of those soldiers were younger than 18 years old. The youngest soldier that Doyle encountered was 16 years old. The reason he believed that many of these kids enlisted was due to the allure of war. They had grown up with stories of WWII and how celebrated the veterans were, and they wanted that same feeling of accomplishment.

Infantry

After the first two weeks, Doyle joined Company C, 1st Battalion, 2oth Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division. Doyle’s unit was one of the main forces who went in on three month long patrols in the swampy environment of Vietnam. Doyle particularly did not like being out for three months at a time, as you would not have an opportunity to shower or bathe for those three months unless you ran into a large creek. While Doyle was on patrol, he and his fellow soldiers did not run into too many enemy soldiers. Actually they ran into booby traps, explosives to be exact. Even though he and his men only ran into two booby traps in the year he was in Vietnam, the men were typically terrified that they would run into the traps.

“Booby traps you don’t know where they’re at. You walk up on them. You don’t know where they’re coming from. Most of the time they’re on the main trail. Ho Chi Minh Trail was one of them. One of them they hit. Then one of them was up on top of a mountain. But a trail was just grass. I guess two companies up there went to stand up to leave. All of them was fixing to leave, and when everybody stood up it went off. By the time you heard it, it was over with. So, you done watched people beside of you fall down and start picking them up. It was all you could do.”

Doyle often remarked that he would rather be shot at than run into a booby trap, mainly because you have something to shoot back at, but with a booby trap, it is over before you realize what had happened.

As a part of the infamous Company C, 1st Battalion, 2oth Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division, who committed the massacre at My Lai a few months before Doyle arrived. Doyle said that they would often be stared at and there was a silent agreement between everybody that they not mention My Lai, as it was considered incredibly taboo.

Drugs

Drug use was rampant with the United States military during the war. This was possibly due to how well marijuana grows in Vietnam’s climate, along with a combination of the drug being illegal in the United States. Doyle never did any drugs, but while he was in Vietnam, he witnessed many soldiers using drugs. Doyle often walked point while on patrol, and said that there was only one soldier that he trusted to have his back. He did not trust many of the others because of how much marijuana the others smoked. When his group would come near a small village, which happened about every other day, they would be approached by a significant number of children. These children would have loaf bread sacks packed full of marijuana and would try to get the American soldiers to buy a bag for $25.

Guard Duty and Ole Smoky

Every night everybody would pull guard duty with an area that they were to watch for a few hours before waking up their partner in the foxhole with them to start their shift. Doyle and everybody else called this man Ole Smokey. Very few people knew his real name. He was called this because of how much marijuana he would smoke. With about a month left before returning back to the United States, Smokey was on guard duty one night, however he had smoked too much marijuana that day, and feel asleep. In the morning, when the sergeant woke up and found out that Smokey was asleep and no one was watching that area of the perimeter, the sergeant put the barrel of his M16 in Smokey’s mouth and threatened to shoot him right there, and after being calmed down, the sergeant backed off.

Soldier Deaths

While there were a large number of soldiers that were killed in Doyle’s platoon from booby traps, the majority were killed from simple mistakes from friendly mortar teams and those who would set booby traps.

“All night you’d hear mortar rounds. And then one of them on the mortar teams supposed to have where we’re at. They wrote it down where we was at. They had a new guy come in and he thought that’s where you bombed. He set that thing on us.”

“And we heard that thing and me and Jim had a sleeping position he got over there and I had one over hear and we got down in them things and we heard it quit whistling I said its fixing to hit us. Our mortar team there was two right in the middle of us right next to the foxhole and jumped down into the foxhole and got their heads cut off. Feet. They just lacked that much being down. They lacked 30 days going home. That ole boy that done it in that other company. We had to go through that company the next morning. We walked right through them. Our boy went crazy. He went crazy when he heard that it killed two.”

Death has always been inevitable in war. During the years that I have known Doyle, whenever he would talk about his time in Vietnam, he often remarked that he never thought that he would make it back. Out of the three men from my family, only two came back, my granddad and Doyle. Their cousin, however, did not make it back due to a booby trap that the Northern Vietnamese troops used. In the two times that Doyle’s unit hit a booby trap, it was over in an instant. One second they would be walking like normal, and the next second, several of the men would already be on the ground dead. There was no option to stop, so they would have to call in the location and keep moving.

Post War

Doyle left Vietnam exactly a year after he arrived. Soldiers in Vietnam had become extremely aware of how poorly soldiers were being treated when they return to the United States, and that was a concern for Doyle. Fortunately, the military began sending soldiers back to the United States at times when the plane would land at the airport between midnight and two a.m. After making it back home to Boaz, his family graciously welcomed him back. For the most part, people were surprised to see Doyle back after only a year, and while they were glad that he made it back home safely, there was no hero’s welcome as we had in past wars.

Doyle mentioned that the hardest part of coming home was sleeping. At first, he was afraid that he may have a mild case of PTSD, however after a visit to the VA, they told him that it was just part of getting used to being back home. So, for a few months he couldn’t sleep inside, so he would go and lay near the pump house and stare up at the stars like he would when he was in Vietnam.

While the Vietnam War still leaves a sour taste in many people’s mouth, Doyle said that is not the case for him. Doyle was glad that he went. Even though he was glad, he said that the only way to move on and not develop PTSD was to have left everything behind you when you stepped off the plane when you landed back in the United States. That is the only way that Doyle believes that you can truly move on from something as traumatizing as war.

Transcript

http://adhc.lib.ua.edu/vietnamwar/interview-transcript-4/

Interview Audio

https://soundcloud.com/user-710654514/oral-history-interview-doyle-ross-part-1

https://soundcloud.com/user-710654514/701-0089a

Extra Reading

- Investigation of the My Lai incident : hearings of the Armed Services Investigating Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, Ninety-first Congress, second session, under authority of H. Res. 105

- http://library.ua.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=1510237

- The Vietnam War on trial : the My Lai Massacre and the court-martial of Lieutenant Calley

- http://library.ua.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=1493467

- Shear, Wayne G. “The Drug War: Applying the Lessons of Vietnam.” Naval War College Review 47, no. 3 (1994): 110-24. http://www.jstor.org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/stable/44637329.