Paul Gilson was born as Dung Van Tran in the Xuan Loc province of South Vietnam. His exact birthdate is unknown but was estimated to be October 15th, 1969. Gilson spent the first few years of his childhood living in a small hut on stilts in the provinces but has little more than vague recollections of his childhood home or his biological mother. It was believed that his mother was a Vietnamese National and his father was an American Soldier of Hispanic descent, which meant he would be considered Amerasian.

Life as a Mixed-Race Orphan

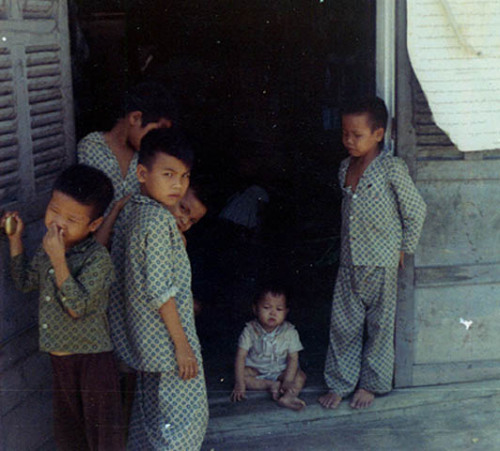

In 1974, Mr. Gilson’s biological mother left him in the care of an orphanage in a city near their village in the Xuan Loc province. Gilson’s biological mother would return to the orphanage periodically to give what little money she could to the owners, but over time her visits became less frequent and eventually ceased altogether. Gilson recalls some of what life was like in the orphanage, but due to both his young age and declining health at the time, his memory is far from complete.

“Um, I remember – you know, there was a – there was a helicopter base near – near the orphanage, and I do remember, you know, hanging out with other kids and looking through the fence watching the helicopters land; you know, talking to the – the soldiers, um, but the – that’s, uh, the limited, um, memories I have of – of … being in the orphanage. “

Paul Gilson

He recalls that he was treated differently by the other children, and says that he believes that it was because he is mixed-race.

“I think – you know, I don’t remember much – I mean, like I said – of the orphanage. Um, but, I did, I – I do know that I didn’t, you know, I didn’t play along with the other kids as much as, uh, you know, that they did with each other. I didn’t hang around with them as much. Um, I, um, you know, as I grew older and looked back and the history and the – and, you know, watched all the different documentaries about Vietnam, I – uh, I pretty much figured out why, which was that, you know, Vietnam was, you know, their culture was very closed, and having a mixed – a mixed child was – was, uh, somewhat taboo, you know. They – they treated the – the Amerasians very poorly.”

Paul Gilson

It was later discovered through DNA testing that Gilson’s biological father hailed from France, thus making him Eurasian rather than Amerasian. Though this may seem like little more than a semantic difference, it demonstrates the difficulty of determining heritage, lineage, and parentage for Eurasian and Amerasian people who were left to piece together what little they could find of their past lives after the French abandonment and American occupation of Vietnam. Their struggles are compounded by the racism and discrimination that they receive in both Vietnam and Europe/America, making them outcasts by birth.

Being Adopted by American Parents

After living in the orphanage for some time, Gilson was adopted by an American family. They took him with them to live in an American apartment complex in Bien Hoa, which lies about an hour outside of Saigon. Gilson recalls marveling at the luxuriousness of the complex, and at the lush lives that the Americans led.

“…when, uh, the American couple took me out [of the] orphanage and brought me to their complex, um, that was like a Disneyland for me. I mean, they had [a] swimming pool, television, everything that you didn’t have, um, being a kid in an orphanage; I mean, I din’t know how to swim, but I remember the – the Americans trying to teach me and the – the clear blue water of the pool, and that – I – that stands out to me.”

Paul Gilson

But there would soon be trouble in paradise; Saigon fell shortly after the American couple adopted Gilson, and they had not had time to acquire the necessary paperwork for him to be able to evacuate the country with them. He was going to have to return to the orphanage and face whatever fate awaited him as a sickly mixed-race child in a newly-communist South Vietnam, and it was not likely to be a very good one.

Sue Gilson and the Evacuation to the Philippines

Fortunately for Gilson, his luck was about to take a turn for the better. Sue Gilson, another American resident at the apartment complex that the American couple was living in, was able to take the young boy so that he would not be abandoned during the evacuation.

“[The first couple said] ‘If you can take him, take him, otherwise he’s gonna have to go back to the orphanage.’ And I think that’s when my [adoptive] mom decided, I guess, that she wasn’t ready to have a – a – a child, but she decided to take me because I think they, uh – everyone knew what would happen to – to mixed kids if they stayed, and when the communists got there.”

Paul Gilson

Mrs. Gilson’s father was a prominent member of the Catholic clergy in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and had several connections to state senators and representatives who were able to pull a few strings and acquire the paperwork that the two needed for Gilson to be able to join the evacuation as an Amerasian refugee.

“Operation New Life” and “Operation Babylift”

Amerasians and other mixed-race Vietnamese refugees were given priority over other refugees during the airlifts because they were in the most immediate danger; after the fall of Saigon, Viet Cong troops and members of the DRV began killing mixed-race Vietnamese citizens indiscriminately as part of “The Bloodbath.” This crudely-named event was a mass-murder committed by the North Vietnamese to rid the country of “undesirable elements” so that they could build “One Red Vietnam.” The murders were not committed out of malice or retaliation but were rather the execution of a political and social purge. The American campaign “Operation Babylift” was a large-scale operation in which US troops airlifted over 3,000 infants to Clark Air Base in the Philippines; “Babylift” was a part of the much larger “Operation New Life” where 110,000 Viet refugees were airlifted to Clark Air Base to save them from “The Bloodbath.”

Clark Air Base

After being cleared to leave Vietnam, the two were airlifted to Clark Force Base in the Philippines. Shortly after arrival, Gilson was placed under medical quarantine; he was diagnosed with typhoid fever – a bacterial infection caused by ingesting contaminated or unsanitary food or water. Gilson recalls that the American doctors and nurses on the base were all extremely nice to him, and many of them would give him treats and candy. He had to have blood drawn every day, but the nurses tried their best to make his stay as comfortable as possible. He remembers slowly recovering, and eventually being able to play hide-and-seek with the nurses; the game was extra high-stakes since he was not allowed to leave the quarantine ward, and the nurses had to catch him before he could make his escape into the general hospital. Gilson also recalls his first taste of American food – Kentucky Fried Chicken. Slowly but surely, he recovered and was finally medically cleared to fly home to the United States. But by that point, all of the Vietnamese refugees had already been airlifted to the States, and Gilson and his adoptive mother were stranded without the necessary paperwork to get home yet again. Thankfully Sue’s father was able to request aid for his daughter and her new son for the second time, and they were granted permission to fly home to Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Arriving In Green Bay and the Initial Culture Shock

After his arrival in Green Bay, Gilson recalls his first few months adjusting to his new life. He spent the first few weeks in his new home tending to household chores – cleaning, doing laundry, washing dishes, and the like. When his adoptive mother asked then six-year-old Gilson why he was doing all of these things, he revealed to her that he was under the impression that she had brought him to America to be her houseboy. Mrs. Gilson quickly corrected him and informed him that he was being adopted as her son and that he did not have to do chores for her, which came as a shock to the young boy.

“…houseboys [were] essentially, you know, maids, um, cooks, you know, gardeners, things like that – the – the standard service per – or, personnel that most American, um, couples had that were living in Vietnam. So they – they brought in, you know, cooks, and – and laundry people and stuff to take care of everything, and – and I was under the impression that that was why I was there. When my [adoptive] mom told me no, I wasn’t, I was – you know, I was being adopted, then I – I, I thought – I didn’t believe her at first. I thought I was just there to be, you know – to take care of – of the household and – and do chores.”

Paul Gilson

Vietnamese House Boys and Prostitution During the War

Though it may seem strange and a little sad, houseboys were very common in Vietnam during the 1960s and early 70s. Due to the sheer volume of children and orphans, many Vietnamese parents and caregivers simply could not afford to feed all of their charges. The Americans offered a solution – the boys would clean their houses, do their laundry, cook their meals, and wash their dishes, and in exchange, the boys could live with the Americans, who would feed, clothe, and home them as long as the boys worked for them. As far as living conditions go, a steady supply of food and a guaranteed place to sleep were a valuable commodity that many families and orphanages were simply unable to refuse. Sadly, these positions were only offered to Vietnamese boys; Vietnamese girls were forced down a much more carnal path. It may seem unthinkable to us today, living in a developed nation untouched by the hand of war, but during the height of the American involvement in Vietnam, many Vietnamese people did not know when or where their next meal would come from, and they had to survive by means that we may deem disgusting or unthinkable. War changes society and society dictates the behaviors of the people who are living in it.

Growing Up as an American

After settling into his new home, Gilson began attending school, making friends, and living life as a regular little boy. But unlike most little boys in America, he had to make some serious decisions about how he wanted to move forward with his life as a Vietnamese Amerasian (or assumed Amerasian, at the time) adoptee; Gilson’s adoptive mother strongly encouraged him to network with some the Vietnamese refugees in the area so that he could learn to speak Vietnamese fluently and maintain a connection to his cultural roots. Gilson, however, wanted nothing of the sort. He had decided that he wanted to live his life as a regular American boy and that he did not want to have any connection to his former life as a Vietnamese national. He wanted to be American through-and-through and even decided to change his name from Dung Van Tran to Paul Gilson. Though she had some reservations about allowing her young son to make such a drastic decision, Sue Gilson wanted to ensure that he was happy and at home in America and obliged Gilson’s requests to distance himself from his Viet heritage.

Reflecting on His Journey

Gilson is now 50 years old, and he resides in Green Bay. When asked if he regrets his decision to distance himself from his heritage, Gilson states that he does indeed regret it. He wishes that he had learned to speak Vietnamese so that he could engage with other Viet people who he comes in contact with, and he wishes that he had maintained a part of his heritage that he could pass down to his sons. Gilson also says that though he acknowledges that his journey to America was much less challenging than many refugees, he wishes that he had faced some of those challenges so that he would have more in common with them. Gilson said that he feels that he does not have a perfect place anywhere; he is not quite American because he was born in Vietnam to a Vietnamese mother and a French father and came to the country as a refugee, and he is not quite a refugee because he was brought to America under special circumstances and was adopted by an American. He wants to return to Vietnam but feels that he has no place there either since he has spent most of his life in America, and though he is half-French he feels that he has no place in France because he has never known his father and did not know that he had any European blood in him until recent years.

The Amerasian/Eurasian Refugee Identity Crisis

Gilson’s conflicted identity is not unique to him; many mixed-race war refugees, and war refugees in general, face the same problems. The issue lies herein: many do not know their parents and cannot trace their parentage, lineage, or heritage; many do not know when or where they were born and feel that they have no solid place of origin; many do not know whether they have relatives at all, or if any that they may have are surviving, and cannot reconnect with their biological families. War shatters nations, families, and individuals, and makes it nearly impossible for the survivors to know with any certainty who they are, where they are from, or who their families are – let alone where they are. Though there are organizations dedicated to reuniting families that were separated by the Vietnam war, time and innumerable other factors make reuniting impossible for nearly all families.

Reconnecting With the Past

Paul Gilson plans to travel to South Vietnam in the near future, and he and his sons have decided to legally change their last name back to Tran.