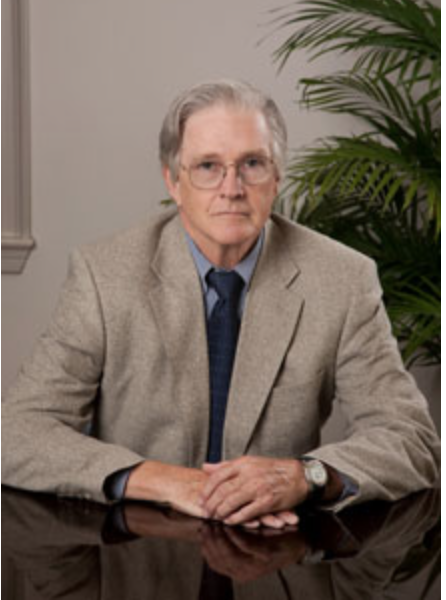

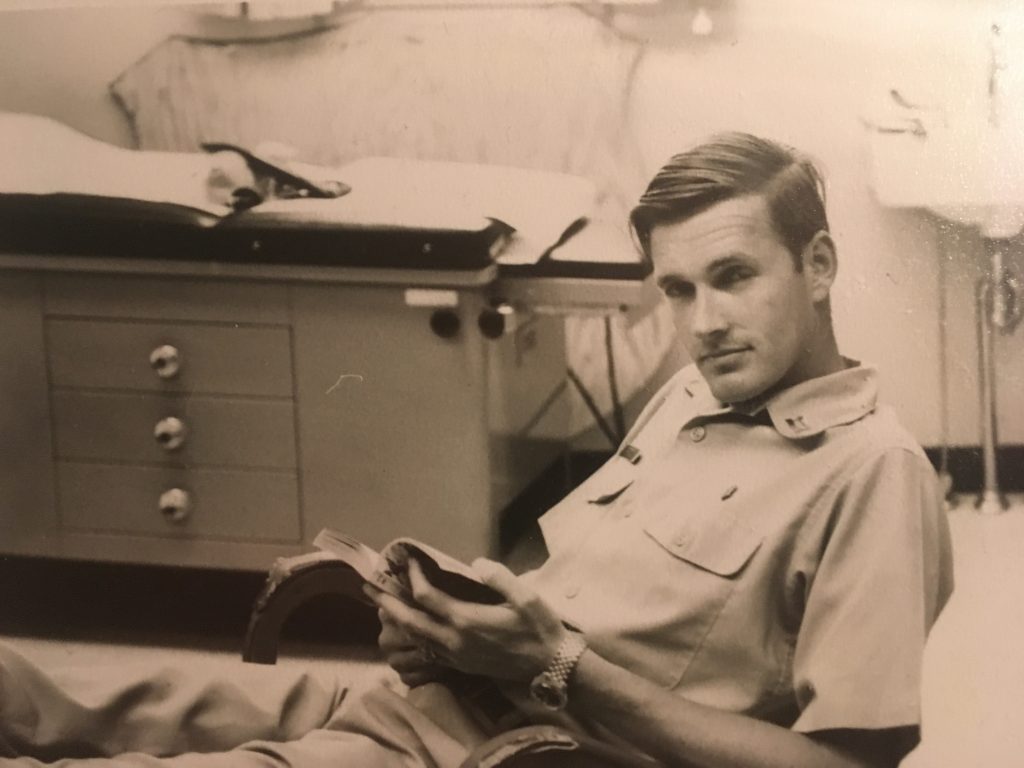

Dr. Robert Patton was born in December of 1941 and grew up in Mobile, Alabama. He graduated from the University of Alabama and then attended the University of Alabama School of Medicine where he graduated with honors in 1967. After a year of internships, he was drafted into the United States Airforce where he served as a Captain from 1968-1970 and spent a year on the Takhli Air Force Base in Thailand. He and his wife, Barbara, have three sons, Michael, Richard, and Forrest, and they currently live in Opelika, Alabama.

The Doctor Draft

With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Congress passed an amendment to the Selective Service Act of 1948 to include the drafting of physicians. All physicians and dentists under the age of 51 were required to register, and this would last until the end of the Vietnam War. In 1967, to deal with the escalation of the conflict in Asia, Congress began restricting medical exemptions and about 6,000 of the 9,000 doctors graduating from medical school each year were drafted by the Department of Defense. Recent graduates like Patton were allowed to choose their desired branch but had little doubt that they would be called up:

“I think we think we picked it when we started medical school. We all were drafted of course. And I think when school started, we went ahead and made a choice… We all signed up for the draft when we were like 17, and we pretty well knew it was going to happen.”

Just as in the regular draft, many physicians were not pleased with events in Vietnam and did not want to go. Whether from moral issues, disagreements with how the United States was handling the war, or just not wanting to leave one’s family, the Doctor Draft was not popular. Patton was no different:

“Well, I was a skeptic and I think I even talked to your grandmother about going to Canada. I mean, I wasn’t happy. Most of us weren’t, but it would have been a horrible thing for your family to do that. And some people did it. To run away or avoid the draft and go to Canada, you couldn’t recover from that. So most of us opposed to that issue would just do our duty and get through and come out.”

Instead of heading for the border, when Dr. Patton received his orders, he traveled to Fort Riley, Kansas to receive the necessary training, and then near the end of 1968 shipped off to Thailand:

“When I finished my internship we got our orders and I had to go to a place in Kansas and then, later on, I spent a week before I went to Thailand to do jungle medicine injuries and all that kind of stuff. And we had a little small arms training, nothing major, but we had a couple of weeks of that.”

The Airforce in Thailand

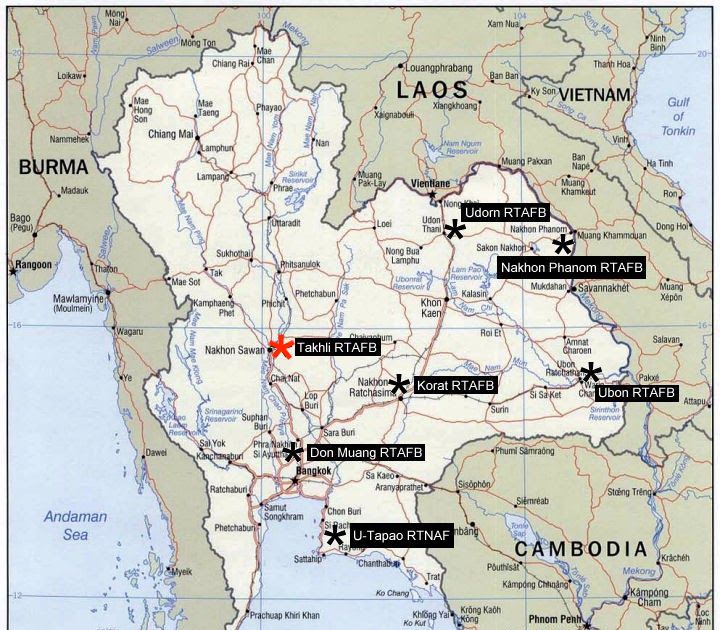

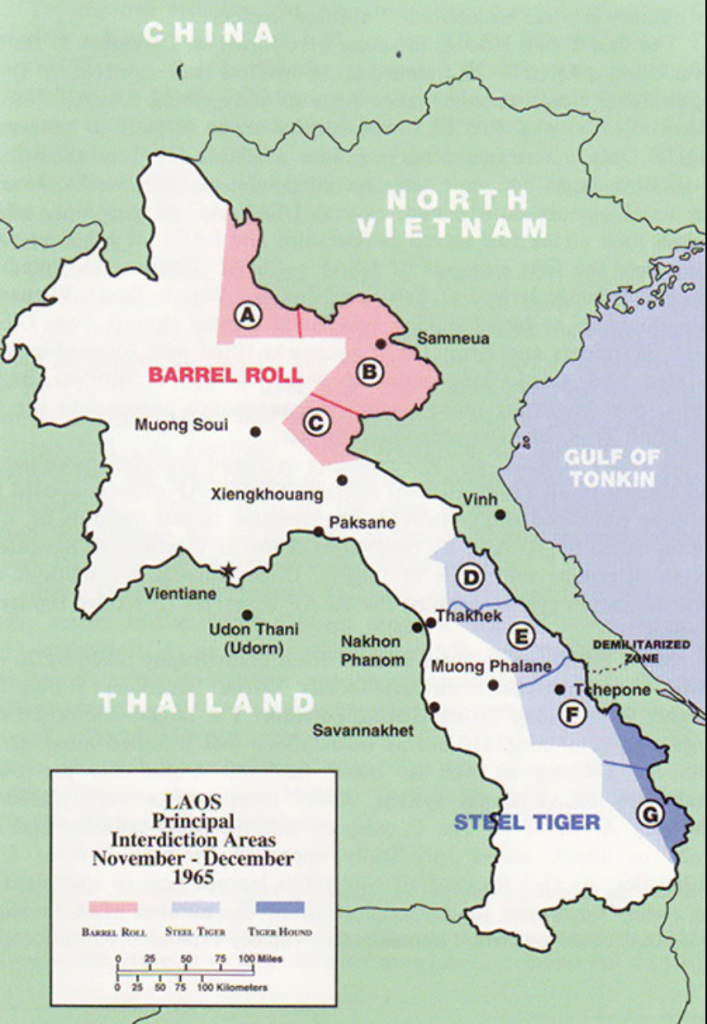

Dr. Patton would be stationed at one of the five major USAF bases in Thailand, each with its own unique mission. Political considerations and fears of a civil war in Laos spreading into Thailand limited America’s willingness to build new bases, but they started upgrading five Thai bases to meet USAF needs in 1961.

“I think there were maybe five bases. All of them were a different kind of mission. Some of the B-52’s that were bombing in various places, and we were tactical air command with the particular airplane we had. And there was some F-4 fighter command’s up above us.”

Operation Rolling Thunder

The bases in Thailand allowed the Air Force to perform bombing operations over North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder was the initial bombing campaign conducted by the Air Force and Navy between 1965-1968. It began as a show of force and determination by the U.S. but turned into a way to boost the falling morale of the South Vietnamese. It was winding down as Patton arrived.

Tet Offensive

The massive coordinated attack by the North Vietnamese starting in January 0f 1968 into South Vietnam was called the Tet Offensive. Though the North Vietnamese suffered massive casualties, it marked a turning point in the war as it showed the U.S. that there would be no quick victory in Vietnam. Patton would arrive in Thailand while the Tet Offensive was still underway and many of the missions conducted from his base would be counteroffensives against the Viet Cong advance.

Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base

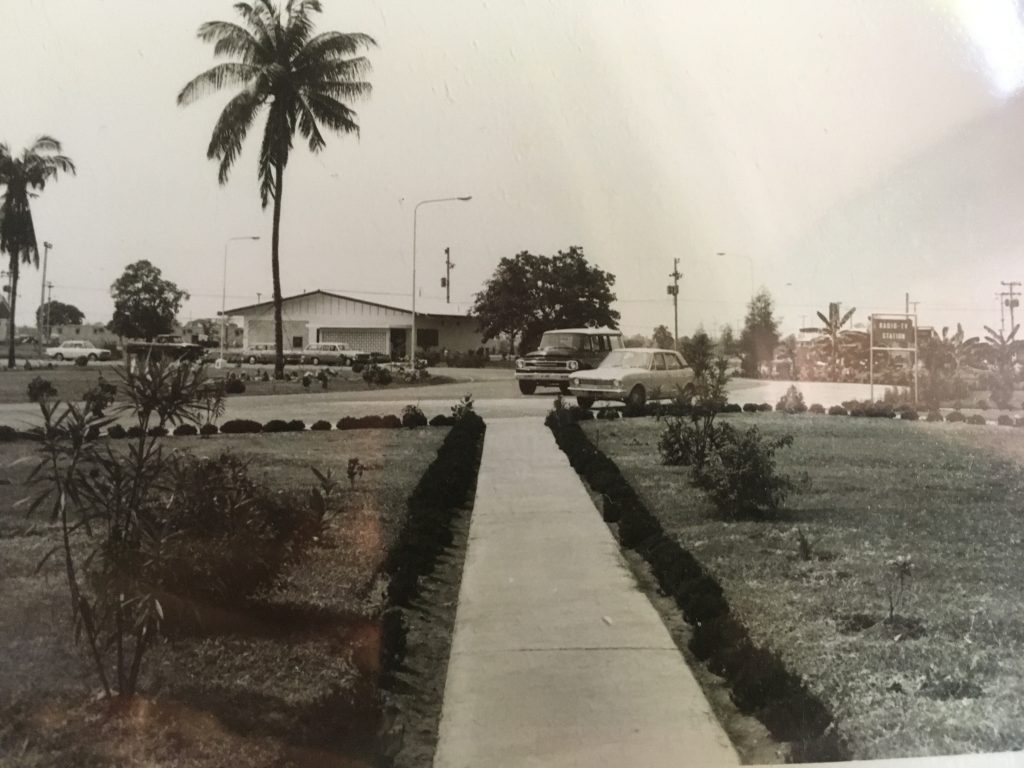

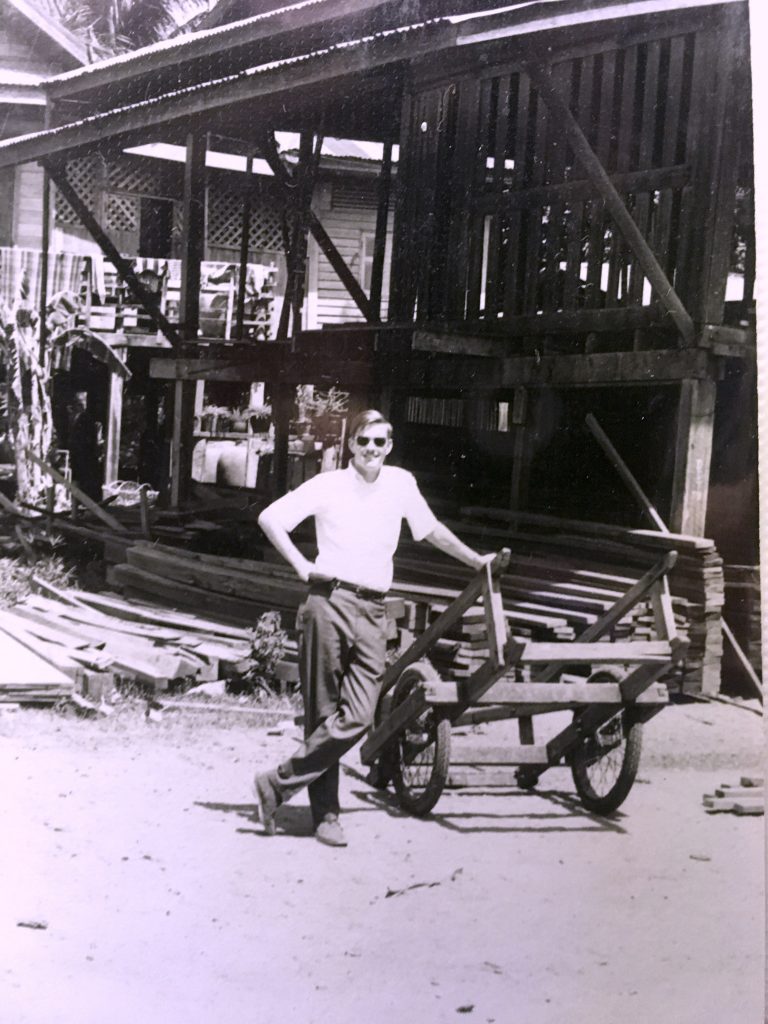

The particular base that Dr. Patton was stationed on in Thailand was located about 150 miles north of the capital, Bangkok. It was originally a Thai Air Base, but it was used by the U. S. Air Force as a front-line combat base during the Vietnam War.

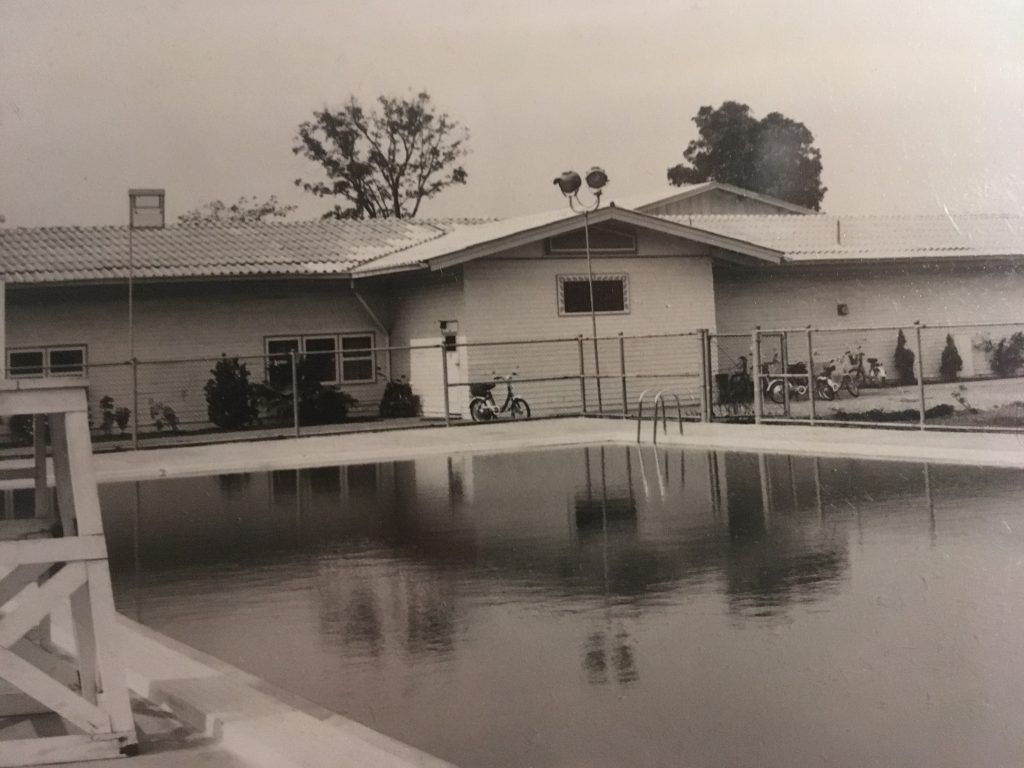

“It was like a little city, you know, everything a city had, you had to have all that. Cause there were a lot of people. Like I say, we had about four or five thousand people running that base.”

The Pilots and Their Planes

An Air Force base revolves around the pilots and their aircraft. The Takhli base was no different and was home to the F-105D Thunderchief and the F-105G Wild Weasel. The F-105 was a supersonic fighter-bomber capable of more than 900 mph at sea level and over 2 times the speed of sound at high altitude. They were faster than a MiG-17 even when laden with bombs, and one “Thud” as they were called, set a 100-kilometer closed-course world speed record of 1,216 mph in 1959. Many of these pilots did not have the same misgivings about the war as others did. According to Patton:

“The pilots loved it. As they told us, it’s the only war we got. You know, combat pilots are combat pilots to be combat pilots. They liked to fight, and they liked to fly.”

The “Thuds” were backed up by EB-66s which provided radar jamming protection to the fighter-bombers. The North Vietnamese used radar signals to detect incoming aircraft, guide their MiG fighters, and aim surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and antiaircraft guns. EB-66s would escort the F-105s on their mission to disrupt radar signals along the way.

“One of my friends was a flight surgeon, and he flew on some missions over Vietnam with those radar jamming B-66s… These airplanes would take off and as fast as they took off, they’d turn on the afterburners and within about 50 miles they’d have to get refueled cause they’d burned up all their gas.”

The final piece to the puzzle was the KC-135 refueling tankers. The Takhli base would often have several of these circling the area to refuel the fighters and bombers. They were vital to any long deep bombing run into Vietnam. During the Vietnam War, tankers would complete more than 800,000 refuelings.

While relations between pilots and the rest of the base were normally pretty good, doctors and pilots did not always get along:

“You know, the doctors and the pilots didn’t really mesh together very well. First of all, we sometimes outranked them. We just immediately became captains just by signing the dotted line. So they didn’t necessarily like that. But we didn’t have any conflicts. We saw them all. Flight surgeons took care of most of the pilots, anything special. But if they got sick in the middle of the night and we were staying in the hospital on call, we would take care of them.”

Life on the Base

The base may have revolved around the pilots, but it still required thousands of others to make the missions possible. It had all the amenities you could want including a pool, church, officer’s club, library, hospital, and transport to the local city or down to Bangkok for a day.

“We had a library and church…The hootches we lived in weren’t fancy. We had a big officer’s club where we ate and of course we had the hospital and we could fly in and out of there on airplanes anytime we wanted to, wherever we wanted to go. And we were right near railroads, and we got on some of the Thai railroads. Made some trips. Yeah, it was a nice base. It really was.”

Living on an Air Force base has its ups and downs. Aircraft taking off at all hours of the night was a constant annoyance, but there were perks as well. They could ask for anything they needed, and it would get shipped in from Japan. For Patton, this meant the nicest camera that he could get. There was also the chance to fly in the fighters with the pilots though this stopped once a doctor got killed over Vietnam.

“I lived right next to where, you know, where they were and with them taking off every night at three o’clock in the morning when you’re trying to sleep. I mean, they were really loud. And then I had, one of my friends on the base was a flight surgeon and he flew with them a couple of times. And then eventually what happened is it was some doctor who was killed flying out of Vietnam on some mission. I don’t whether it was anti-aircraft or whatever. And they came out with an edict that doctors couldn’t fly.”

Responsibilities

Having highly trained medical professionals on site greatly improved the quality of care that could be provided both to those living on the base but also to the local Thai people as well. People like Dr. Patton made it possible for the Air Force to operate effectively. The work of the physicians was surprisingly similar to work back in the States except with more limited resources:

“It was about three or four of us taking care of 5,000 people. And we were on call at night and we’d have to go in and spend the night in the hospital and we’d see all the people get sick in the middle of the night and we had people in the hospital, and if there’s anything beyond what we can take care of them and we would air it back on to Japan. You could call an airplane in and pick people up in a minute… I think that the medical care we gave was really good. I mean, I had one guy who was there with me who had had at least a year of internal medicine before they took him in. So, he had that background and, you know, we could do minor surgery and things like that.”

The type of diseases they had to deal with were different due to the tropical climate, but because the base did not see any combat, there was little in the way of combat injuries to deal with:

“We had some tropical diseases like dengue we took care of, and we didn’t do a lot of trauma. We had one aircraft accident on the base and unfortunately, they all died of injuries as we shipped them out.”

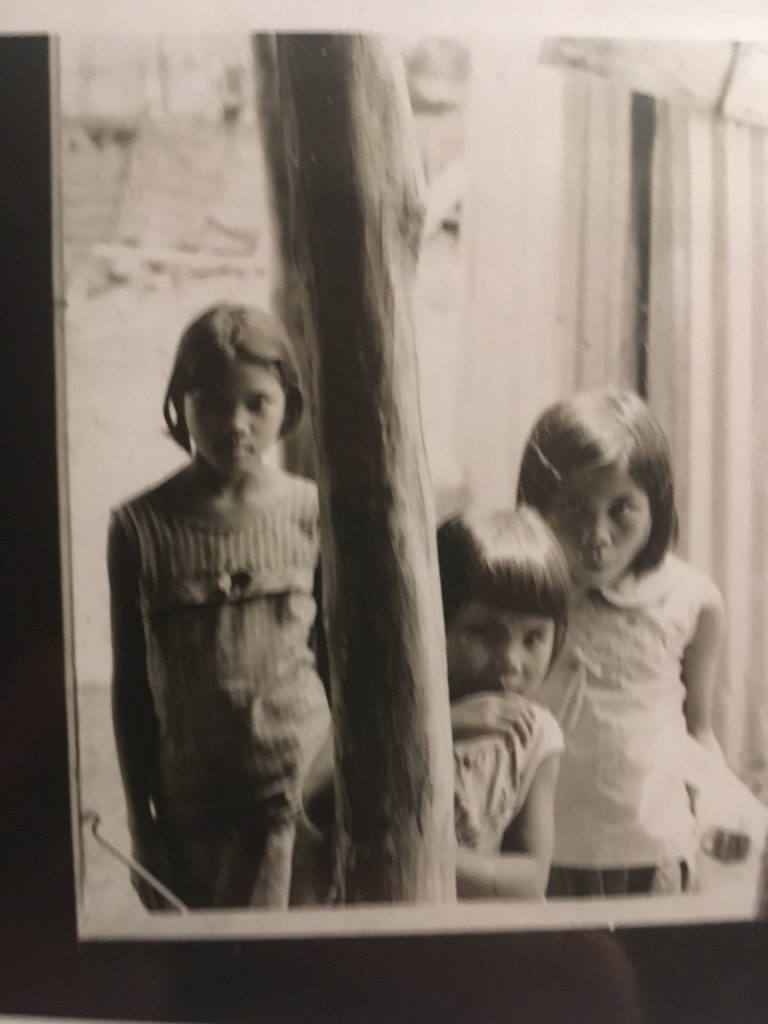

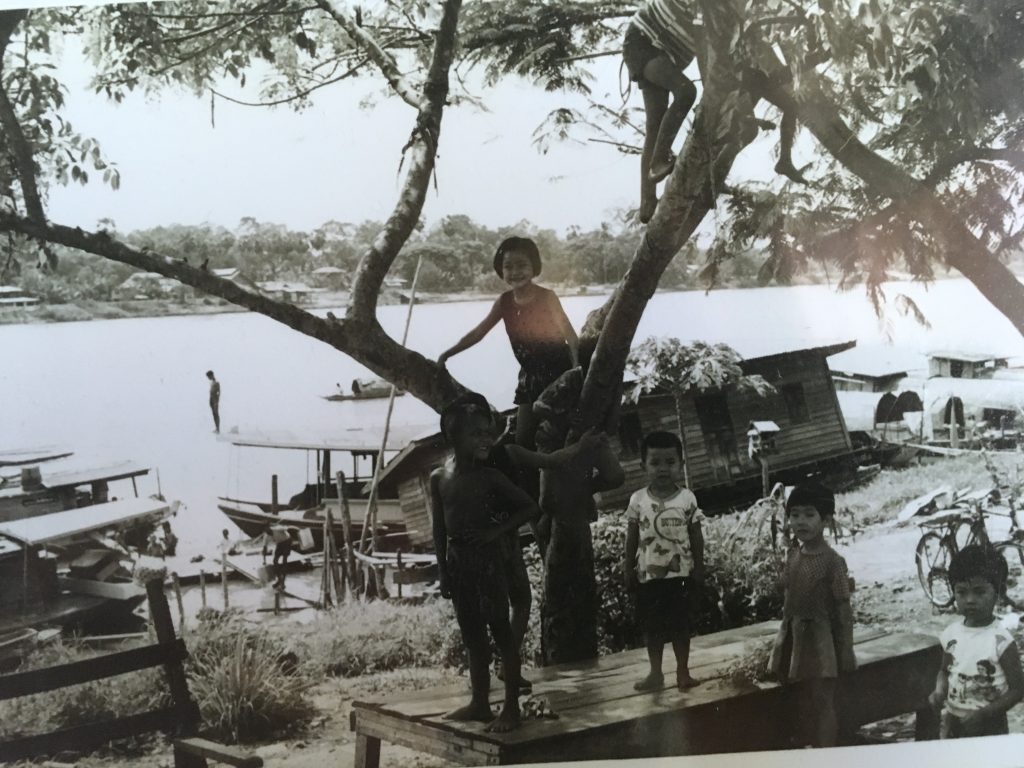

Interactions with Locals

Relief missions to nearby villages were another the part of the physician’s job. As part of an American initiative to gain the support of the Thai people, physicians would go out to nearby villages and set up a clinic for the locals. This would allow the doctors and dentists to provide people with care who had no chance to go to a hospital or receive proper treatment for diseases and wounds. The team would often get overwhelmed by the number of people needing care:

“The area around where we might travel around 50 miles or something about. We carried truck and supplies and go out and you know, go to a village and set up a clinic, and say who all wants to be seen. And then they lined up, and we’d start seeing them.”

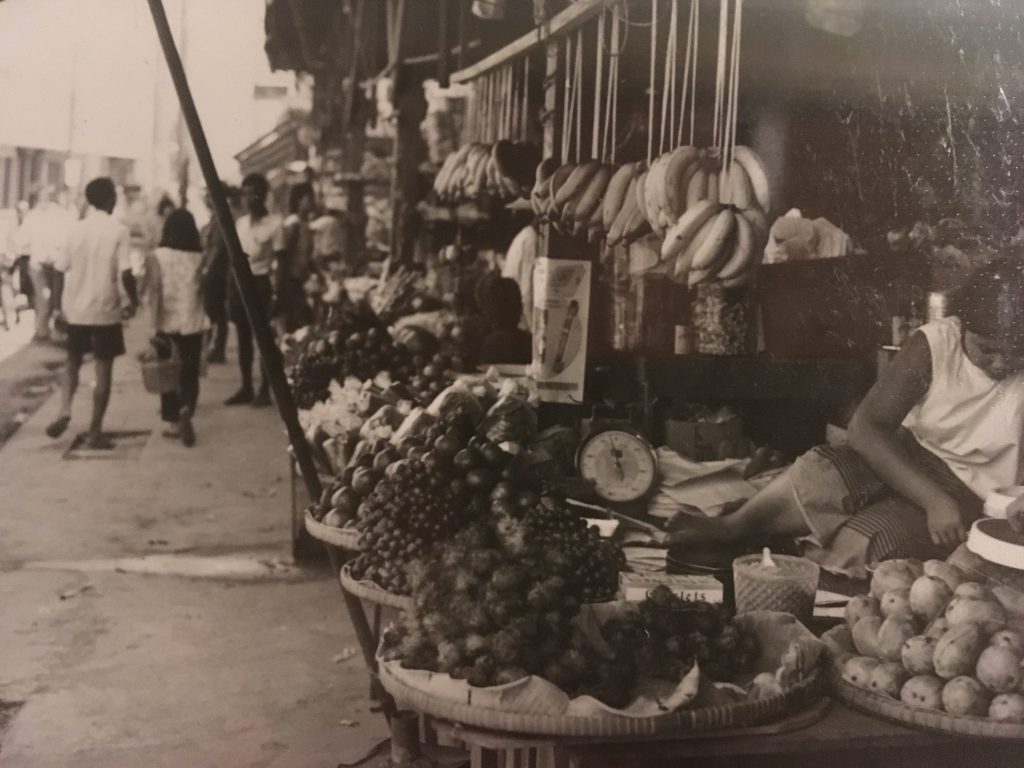

Many Thai people also worked on the bases doing things like maintenance, washing clothes, or providing food, and the large amount of new jobs actually helped the economies of the areas around the Air Force bases.

“The Thai people are really nice people, and I don’t think there was any adverse kind of problems with the Americans and the Thais. Of course, we hired a lot of Thais. The base probably hired several hundred of them to help run the base. They were working everywhere. So it was a big influence on the economy just having the base there.”

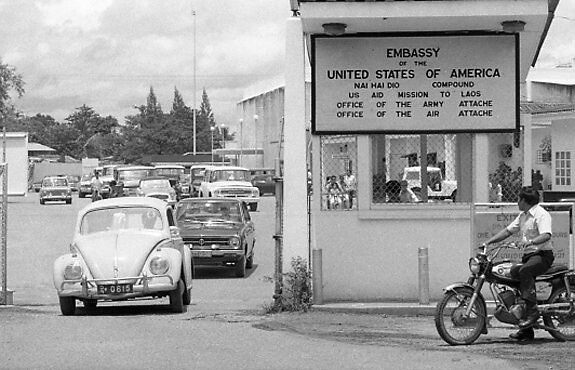

Adventure in Laos

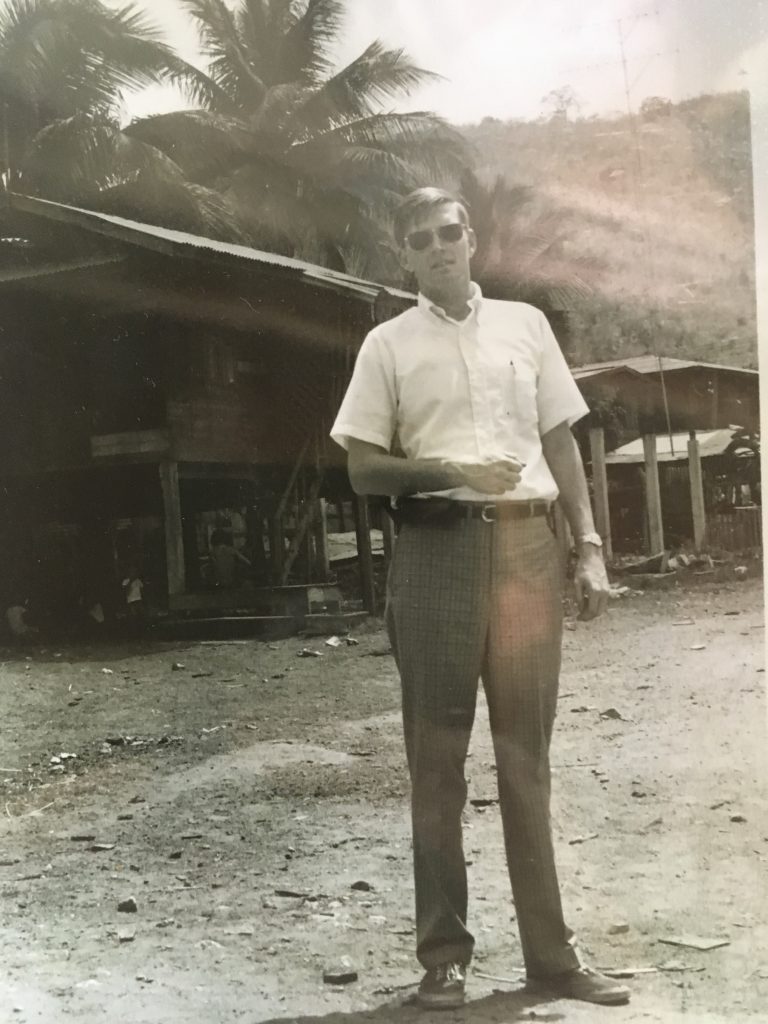

Dr. Patton did not spend his entire assignment on the base. He was also assigned to a USAID clinic at the U.S. embassy in Vientiane, the capital of Laos, for an entire month, and this was probably the most exciting part of his experience:

“I was assigned to the embassy in the capital of Laos. I was told I was to leave all my stuff back and get in civilian clothes and I’d be gone a month. It turned out had some nice people there too. There was an organization called AID. It was an American aid organization. It still works today, and they had a compound of houses and a clinic, and I took care of a lot of their people, and I got to know a nurse and her husband who he was running the AID program there. And they were building schools and all kinds of things. We just ran a clinic.

Sandwiched between Vietnam and Thailand, there was no way that Laos could avoid the war. The Ho Chi Minh Trail, which allowed the Viet Cong to travel to South Vietnam, ran through Laos prompting the Air Force to target Laos with consistent bombardments and the communist ties of the Pathet Lao group that controlled large portions of the country led to the CIA getting involved as well. Through much of the Vietnam War, Laos was embroiled in a civil war between the Pathet Loa and the Laotian Royal Government. The United States provided weapons and support to the Laotian government.

In what is called the “Secret War” the CIA used an airline called Air America to support the Agency’s operations in Laos. By the summer of 1970, the airline over 50 airplanes and at least 30 helicopters dedicated to operations in Laos. During 1970, Air America airdropped or landed 46 million pounds of food into Laos. Air America crews transported thousands of troops and refugees, flew emergency medevac missions and rescued downed airmen throughout Laos, and flew nighttime airdrop missions over the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The CIA denied much of what they were doing during the war, and it is still a controversial topic even today due to the fact that Laos experienced some of the heaviest bombings of the entire war. Over 270,000 bombs were dropped over Laos, and it is suspected that over 80,000 never detonated and each year nearly 50 people still die from these bombs detonating.

So although Dr. Patton was unaware at the time, he was most likely working for the CIA his entire time in Laos. He did, however, notice the Pathet Lao troops walking around:

“That was during the days of the Secret Laotian war with CIA and Air America and all those things going on. So, I guess I worked for them and probably didn’t even know it… The Communist troops were all over the place there and we just, we’d mix, you know. You could see them everywhere you went. And they didn’t bother us in any way.”

A Doctor’s Perspective

Dr. Patton returned home in early 1970. His role as a healer instead of a soldier had given him a distinct view of the Vietnam War. Although he was not directly involved in the fighting, he was able to observe and interact with the local people in a way that almost no one else could. The services he and the other physicians could provide to the Thai and Laotian people not only allowed them to build trust but also allowed them to understand the local people’s needs and wants better than most Americans stationed in Asia and definitely better than U.S. politicians halfway around the world. So his perspective on the war was influenced by interactions with real people experiencing the real effects of the war.

The Doctor Draft ended after the United States pulled out of the war, so never again will thousands of physicians and dentists be called to serve their country so far away from home. In some ways, this is a shame because although the United States lost respect and credibility after the war, the doctors and dentists serving overseas did their part to remind the world that Americans could truly care about the people they claimed to be protecting.

Since his service, Dr. Patton has worked for the East Alabama Medical Center in Opelika, Alabama where he has continued to provide outstanding care in Internal Medicine for over 50 years.

Audio

Transcript

Additional Reading

Fighter Pilot: The Memoirs of Legendary Ace Robin Olds (Book recommended by Dr. Patton)

Takhli RTAFB: During the Vietnam War

CIA Air Operations in Laos, 1955-1974