When the war in Vietnam began, Mike Ryan was a college student. He was using the student deferment to avoid going overseas, in the hopes that the war would end quickly. That would not, of course, be the case, and in October of 1964, just months after his graduation, the soon-to-be Sergeant Ryan entered basic training. This didn’t come as a surprise to him, the course of the war had shown that it was unlikely to end before he graduated.

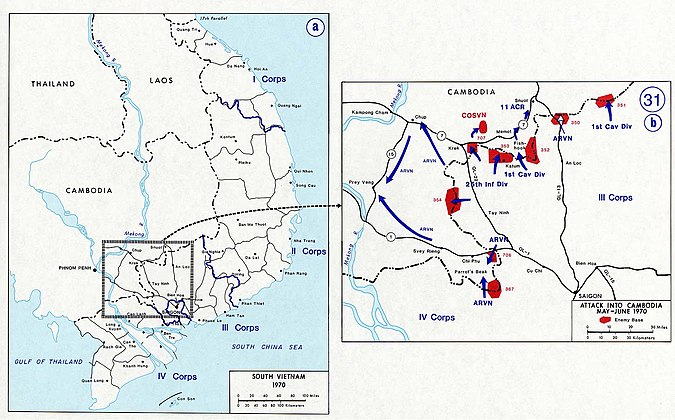

Sergeant Ryan served as a combat engineer in the U.S. Army’s First Cavalry Division from 1969 to 1970. Sergeant Ryan was stationed in the “Fishhook”, an area on the border of Vietnam and Cambodia.

Image source: Wikipedia

As a combat engineer, Sergeant Ryan’s main mission was to clear trees and other obstacles, such as caches of Vietnamese explosives, so that American artillery could have a clear lane of fire. His squad would be sent out with chainsaws and explosives He and the First Cavalry Division were charged with shutting down traffic from the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a Viet Cong supply line through Laos and Cambodia. Being in the Fishhook area, Sergeant Ryan was deeply involved in the American incursion into Cambodia. He, for the most part, did not engage in active combat, but he was “on the receiving end of indirect fire dozens of times”. Speaking in retrospect, Sergeant Ryan said that the most significant operation he participated in was the Cambodian Incursion:

“[The] invasion of Cambodia was a very big deal in the US and the in the States. It wasn’t popular at all, but from my perspective…it was a good thing because we weren’t getting mortared anywhere near as much as we had been before.”

Mike Ryan

Like many servicemembers during the Vietnam War, Sergeant Ryan wasn’t particularly excited to be in the conflict. He said that Vietnam “was a matter of just getting by day-to-day, doing what we had to do, doing the mission that was assigned to us”, and that, like everyone else, he was tracking the days until he got to go home. Upon his return, he found a distinct lack of support for the war in America, a lack of support which he shared.

“I took my uniform off as soon as I got home. And I never put it back on again.”

Mike Ryan

The Cambodian Incursion

“None of the other places that I was…doing anything really meaningful. Never got in the headlines. Never made the front page of the New York Times.”

Mike Ryan, speaking about the Cambodian Incursion

Cambodia, under the leadership of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, was the home of the Ho Chi Minh trail, a North Vietnamese supply trail through the nominally neutral countries of Laos and Cambodia. In addition to the Ho Chi Minh Trail, North Vietnam had other major supply routes through Cambodia, including the port of Sihanoukville and a series of sanctuary bases called “binh trams”. Prince Sihanouk, since Cambodia had an army of only 30,000 men, was ill-equipped to reject the North Vietnamese presence in his country. However, though he claimed neutrality in his foreign policy, Sihanouk clearly favored the Viet Cong, as shown in statements such as the following:

“Quite frankly, it is not in our interests to deal with the West, which represents the present but not the future…South Vietnam will certainly be governed by Ho Chi Minh or his successor. Our interests are served by dealing with the camp that one day will dominate the whole of Asia — and by coming to terms before its victory — in order to obtain the best terms possible.“

Prince Norodom Sihanouk

However, the Cambodian people became discontented with the Vietnamese presence in their country and with Sihanouk’s handling of the situation. On March 18th, 1970, Sihanouk was removed from his office as Cambodian chief of state. This change upset and threatened the balance between the Cambodian and North Vietnamese governments, and North Vietnam “controlled one-fourth of all Cambodia, all areas south and east, and were within fifteen miles of Phnom Penh by April 20” (Guiden, 245). President Nixon, acting with the authority given to him by the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (also known as the Southeast Asia Resolution), chose to end the Viet Cong’s assault from Cambodia, and on April 28th, 1970, American forces entered that nation in what became known as the Cambodian Incursion.

“The unreliable Sihanouk government, which had maintained some small amount of presence, if not control, over the area, had been overthrown and replaced by a government more willing to carry out its neutral duties but less able to do so because of a full-fledged offensive assault launched against the country by North Vietnam.“

Timothy Guiden

For his part, Sergeant Ryan had a more positive view of Sihanouk’s political machinations:

“The King, King Sihanouk, I think his name was, was doing a what I think now was an admirable job of balancing the US South Vietnamese against the North Vietnamese and. keeping his country neutral, relatively. I mean we had troops going in all the time, but still he was doing a really good job and when we invaded Cambodia, we wiped all of that away. That poor man didn’t have a chance.”

Mike Ryan

The incursion was met with immediate protests, the most famous of which being the Kent State protest on May 4th, 1970, in which the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four student demonstrators. Henry Kissinger, then President Nixon’s National Security Advisor, wrote that “the very fabric of government was falling apart” (Drivas, 134). These protests undermined the already-shaky popular support of the war in America, and ultimately served as a factor in the American withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973. News of these protests, and the popular discontent with the war that they represented, made its way across the Pacific to Vietnam:

“We were very aware of it. Very aware of it. And those protests were going on before we ever before we ever got to Vietnam, before we ever left the States. We knew about it and many of us had participated in it…Many of the protests were being led by ex-soldiers.”

Mike Ryan

Image source: Jim Palmer/AP

Although it was very unpopular, the Cambodian Incursion may have been militarily necessary. U.S. Air Force Captain Timothy Guiden, in his 1993 article “Defending America’s Cambodian Incursion”, states that by operating the Ho Chi Minh Trail, North Vietnam explicitly violated Cambodia’s neutrality; since Cambodia failed to end North Vietnam’s operations on the Trail, Guiden argues that Cambodia was never neutral in the first place — it failed to exercise the “duties of neutrality”.

“[Belligerents] need not stand hopelessly by, the victims of repeated attacks by the enemy, simply because of a lack of willingness or ability on the part of the neutral to enforce its territorial integrity.”

Timothy Guiden

It became immediately clear that, in addition to supplying troops in the South from the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong were storing caches of military supplies in Cambodia. As a combat engineer, Sergeant Ryan and his men were ordered to destroy the more volatile supplies:

“I was in Cambodia on the third day. And by then they had discovered a number of caches of ammunition and artillery, shells and explosives and all that sort of crap. And they had to be blown in place and for about 3 weeks I flew around from landing zone to landing zone, blowing [them] up.”

Mike Ryan

By preventing the North Vietnamese from accessing these supplies, Sergeant Ryan and the Army ended a potential threat and helped ensure the safety of American soldiers.

Image source: Wikipedia

Reflections

As a college student during the early war, Sergeant Ryan had a good understanding of the war that awaited him, and his view of the war hasn’t changed much in the decades since:

“I didn’t think that there was a war that we should be in. I didn’t think that we were fighting it in the right way. I was – I spent a fair amount of time with South Vietnamese soldiers, and I was not impressed by their dedication or their commitment to the war…We were relying on the South Vietnamese, but they did not support the mission like they should, and in my thinking, they should have been fighting alongside of us. We didn’t see that. We saw them sitting on their asses while we were going out climbing into helicopters.”

Mike Ryan

Even though he wasn’t in favor of the war, and wasn’t well-received on his return, Sergeant Ryan thinks that there’s been a marked change in the perception of the Vietnam War, and the military in general, during his lifetime. Although the public (and the soldiers themselves) didn’t appreciate what the troops in Vietnam had done in the immediate years after the war, he says that he’s proud of his service now. It took 30 years, but people say “Thank you for your service” to him all the time now, which was something that would be inconceivable at the time.

Thinking about subsequent American wars — Afghanistan and both Gulf Wars, for example — Sergeant Ryan sees a distinct difference in the population’s attitudes towards war. He thinks that the Vietnam War’s draft was fair, since everyone should serve their country. Even though there wasn’t much support for the troops from the public as a whole, the draft ensured that no one area of the country was disproportionately affected by troop enlistment. By contrast, even though the soldiers in later wars got vocal support from the American public, Sergeant Ryan argues that the disproportionality of enlistment between regions of the country isn’t as fair as the draft was, and that the draft makes for a more cohesive and democratized military.

Works Cited

Boudreau, William H. 1st Cavalry Division History – Vietnam War, 1965 – 1972, Cavalry Outpost Publications, 1996, www.first-team.us/tableaux/chapt_08/.

Drivas, Peter G. “The Cambodian Incursion Revisited.” International Social Science Review, vol. 86, no. 3/4, 2011, pp. 134–159.

Guiden, Timothy A. “Defending America’s Cambodian Incursion.” Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 1993, pp. 215–270, https://doi.org/10.21236/ada275340.

Ploger, Robert R. U.S. Army Engineers, 1965-1970. Dept. of the Army, 1974.

Rogers, William D. “The constitutionality of the Cambodian incursion.” American Journal of International Law, vol. 65, no. 1, Jan. 1971, pp. 26–37, https://doi.org/10.2307/2199290.

Sutsakhan, Sak. The Khmer Republic at War and the Final Collapse. U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980.

Traas, Adrian. Engineers at War: The United States Army in Vietnam. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 2010.