Interview Summary

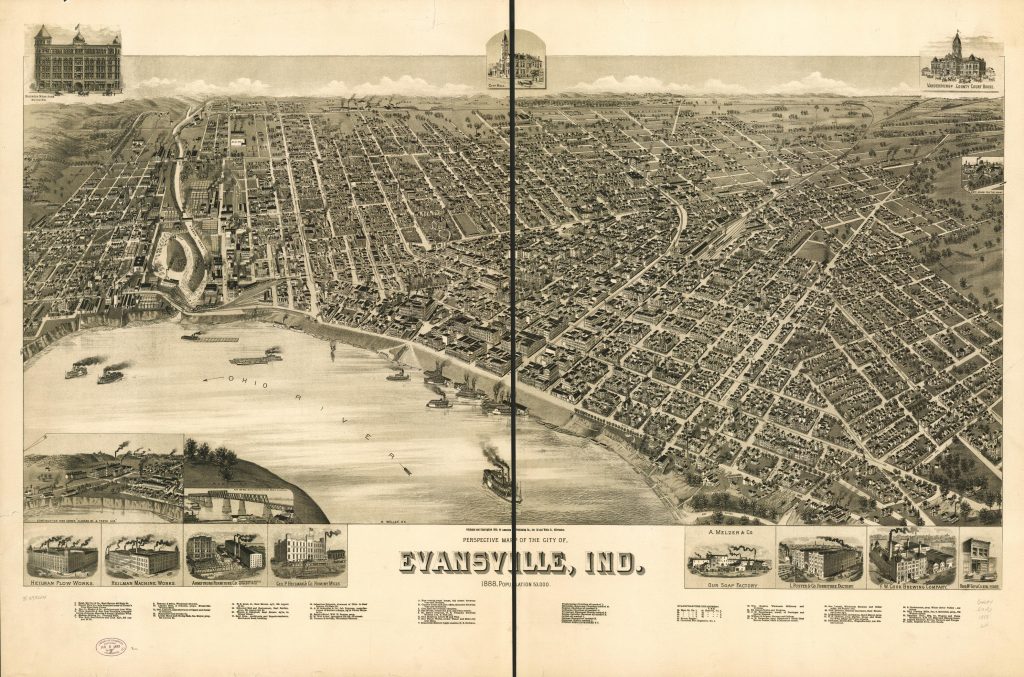

Born in 1947 to a working-class family in Evansville, Indiana, Stephen Reinhart grew up during the post-war baby boom. His father and uncle owned a restaurant, The RNR Diner (Reinhart and Reinhart). However, this was not the direction Mr. Reinhart had in mind for his life, so he enrolled at Purdue University but only spent two semesters there before he realized that he needed to be more mature for higher education.

1967 Reinhart received a draft letter from the U.S. Army but opted to enlist in The Marine Corps. His reasoning for joining the Marine Corps was their more rigorous training and better preparation for his inevitable tour in Vietnam. All tours in Vietnam lasted around one year for the Army and the Marine Corps. Mr. Reinhart served from 1967 to 1971 and spent the final year of his contract in Vietnam. He spent the first three years of his contract accompanying a Navy Admiral throughout the Mediterranean. Mr. Reinhart spent time in Italy, Majorca, and Spain before his tour in Vietnam.

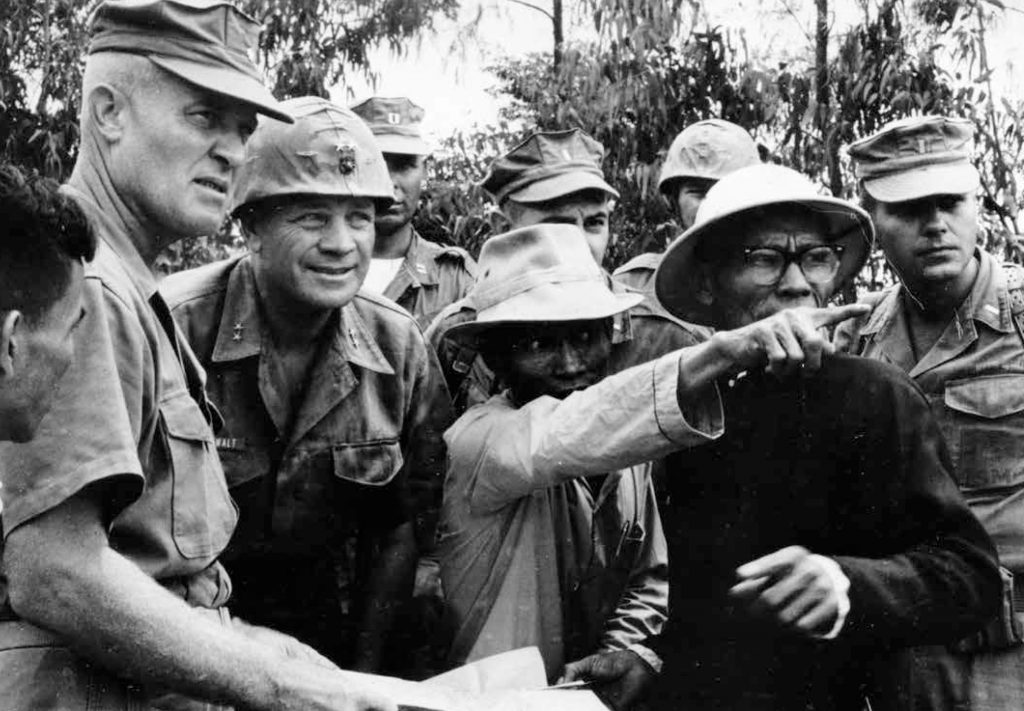

Mr. Reinhart began his tour in Vietnam in 1970. He lived in a village with Vietnamese natives, what they called a “day village,” and did patrols during the night. Reinhart was a squad leader in charge of 12 other Marines, not including himself. His unit worked with the Popular Forces, which he explained were the Vietnamese equivalent of the U.S. National Guard. He told me that the P.F. soldiers were less reliable than they should have been but empathized with their dilemma of fighting against the North while still carrying out their duties to their families and community. The rural nature of the villages differed from Reinhart’s urban upbringing in Evansville. The only house in the village with a floor was the Chiefs house, or what Reinhart called their “Mayor.” The other houses had mud floors, and these homes were called “hooches,” which were a sleeping area on one half, with a living/cooking area on the other, with no wall separating the two. Their squad was accompanied by a semi-useful translator named Thieu, who knew enough English to help them survive Vietnam.

Reinhart’s combat experience was limited to sporadic skirmishes on patrol, save for a few key moments. He was awarded the Bronze Star for his role in the rescue of another Marine while under sniper fire. Reinhart and his squad were patrolling through steep mountains when they came under sniper fire from above them after they breached a tree line into a clearing. One man was injured, and the rest of the squad retreated into the jungle. Reinhart and another soldier decided they needed to rescue the injured man, and as the rest of the squad laid down surprising fire on the hillside, they ventured into the clearing. The two men laid the wounded on a stretcher, and as they were carrying the man back into the safety of the treeline, the other soldier carrying the stretcher was hit and killed. However, Reinhart was still successful in rescuing one of the men.

During his time in Vietnam, Reinhart developed his opinions on the war and the reasoning behind U.S. involvement in the region. He recalls asking his interpreter what his preferred outcome of the war would be, and Thieu replied, “We would like to see the NVA go home, and we would like to see the Marines go home.” Reinhart talked about freedom and communism and how the rural Vietnamese lived so differently than Americans. His empathy towards the plight of the Vietnamese people was evident, and he believed that the Vietnamese probably did have their freedom, although it might be a type of freedom that the Americans could not understand.

I eventually led Mr. Reinhart into a question comparing the withdrawal of American troops in Vietnam to the withdrawal in Afghanistan, a question I later regretted from an interviewer’s perspective. However, his answer was quite passionate and provided interesting context on his opinion of the war. He focused on the wastefulness and the futility of forcing a Western form of government on a culture so far removed from our own. He felt as if the United States had learned nothing from its failures in Vietnam, and he saw the same mistakes perpetuated in Afghanistan. Forcing democracy onto a historically tribal society failed 30 years before Afghanistan; why would it be any different in the 2000s?

After Reinhart finished his contract with the Marine Corps, he returned to Evansville, eventually moved to Newport, Rhode Island, and worked for the Whirlpool factory making A.C. units. He let his hair grow down to his shoulders and grew a large beard, something he attributed to his post-war fogginess. Working for Whirlpool left Reinhart feeling unfulfilled, coupled with the harsh and raw New England winters, and with a semester of credits left over from Purdue before the war, he decided to return to college. His passion for football led him to pick between SEC schools, specifically those with a legitimate business program. Reinhart was admitted only to two of the schools he applied to, only because he applied in late March and April, and he eventually decided on the University of Alabama.

Steve Reinhart lives in Tuscaloosa today and is now a broker at a firm on University Boulevard, the firm being under his ownership. Reinhart was grateful for the skills the Marine Corps instilled in him, specifically his ability to follow and, more importantly, give orders. These skills allowed him to carve a successful life for himself after the war despite coping with the atrocities he witnessed in the jungles of Vietnam.

The Marine Corps in Vietnam

The United States Military broke South Vietnam into three units: I Corps, 2 Corps, and 3 Corps. The Marines primarily operated in I core, the areas surrounding Da Nang up to the 38th parallel, the dividing line between North and South Vietnam. In contrast, the army operated in 2 and 3 Corps, the areas surrounding Saigon.

Boobytraps and the Unseen Enemy

Steve Reinhart was awarded the Purple Heart for being wounded by a boobytrap while on patrol in the jungle. Luckily for him, the trap was inhibited by a large amount of mud covering the device and limiting its lethal potential. Boobytraps were a constant threat for Marines on patrol, and in many cases, marine ammunition was used by the V.C. or NVA soldiers as improvised explosives against the Marines themselves. The V.C. would place these explosives on low-hanging branches, sides of trails, or between rice patties, where they expected the Marines to walk on their patrols. Before a V.C. or NVA assault, the local V.C. soldiers would move into an area and disarm all of their traps so as not to kill or injure any of their own forces. The Marines were able to connect the lack of traps and connect that to an incoming assault.

Combined Action Platoons

Combined Action Platoons, or CAP units, were groups of Marines and local South Vietnamese fighters. These Platoons comprised 15-30 P.F. fighters and 15 Marine Riflemen, but from Steven Reinhart’s personal experience, the P.F.s were only sometimes reliable. Vietnamese soldiers were conscripted to defend their localities and take orders from their Village Chief; however, in practice, they tended to take orders from the Marines commanding the theatre. In 1970, 6 months into Reinhart’s tour, the U.S. military started to ease the amount of incoming soldiers to Vietnam and began disbanding programs like the CAP and CUP units.

Escapism and PTSD

According to a 1973 investigation by the DOD, 28% of soldiers had used drugs before entry into the service. This percentage dramatically increased during service, specifically in enlisted men compared to draftees. Career Soldiers tended to avoid narcotics entirely; most never used them at all. When asking Steve Reinhart about his coping mechanisms for dealing with the intense nature of patrolling in Vietnam, he specifically mentioned alcohol and codeine use. He hinted at further narcotic use beyond alcohol and codeine:

“Let’s say there are some extracurricular stuff that was around that would help you relax.”

21:16

Codeine is a commonly prescribed opiate used to treat pain or to ease coughing. Codeine was not the only opiate used in Vietnam, with 28% of soldiers admitting to using Heroin during their time in the service. 20% of soldiers claim they had been addicted to substances during their time in Vietnam.

Although drugs and alcohol provided a temporary escape from the horrors that surrounded soldiers during the war, that trauma would eventually reveal itself once service members returned to the United States. Mr. Reinhart explains how he readjusted to civilian life after the war. He mentions explicitly being extremely gun-shy and would drop to the ground whenever he heard a car backfire. Soldiers were programmed to survive in Vietnam and brought that training home. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and a study performed by NYU, 11% of male service members had PTSD 40 years after the war, and almost 37% were diagnosed with major depressive disorders.

Safety and comfort were rarities only found in Firebases scattered throughout the warzone. Living in the villages and on patrol, Marines were constantly under the threat of an ambush or unknowingly walking into a boobytrap. Reinhart expressed the anxiety felt throughout the warzone and reveled in the relative safety of the firebases. However, even in the firebases, the threat of mortar strikes was ever present, so Marines were constantly tense throughout their tours of Vietnam.

References

Bronze Star. (n.d.). United States Marine Corps Flagship. Retrieved November 30, 2023, from https://www.marines.mil/Combat-Awards/Article/1831640/bronze-star/#:~:text=Minor%20acts%20of%20heroism%20in

Childs, F. (2013, December 6). What is a Firebase? Charlie Company Vietnam 1966-1972. https://charliecompany.org/2013/12/06/what-is-a-firebase-2/

Cosmas, G., Murray, T. P., & Murray, T. (2013). U. S. Marines in Vietnam: Vietnamization and Redeployment 1970 – 1971. CreateSpace. https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/US%20Marines%20In%20Vietnam%20Vietmanization%20and%20Redeployment%201970-1971%20PCN%2019000309600.pdf (Original work published 2023)

Epicurean, G. (2018, July 8). Soldiers “shotgunning” weed in Vietnam. The Great Epicurean. https://medium.com/greatepicurean/american-gi-soldiers-shotgunning-smoke-marijuana-weed-through-barrel-of-shotgun-vietnam-war-1970-video-photo-4cd250d13d8

MedlinePlus. (2017, December 31). Codeine: MedlinePlus Drug Information. Medlineplus.gov. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a682065.html

MORRIS, C. (2013, November 6). Finding peace 45 years later. Cody Enterprise. https://www.codyenterprise.com/news/people/article_aea6c6d6-4731-11e3-80a2-001a4bcf887a.html

Military Antiques and Museum – – ML-1024, Vietnam War US Bronze Star Medal – Named – $74.95. (n.d.). Militaryantiquesmuseum.com. Retrieved November 30, 2023, from https://militaryantiquesmuseum.com/ml1024-vietnam-war-us-bronze-star-medal-named.15256.archive.htm

PTSD and Vietnam Veterans: A Lasting Issue 40 Years Later – Public Health. (2014). Va.gov. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/publications/agent-orange/agent-orange-summer-2015/nvvls.asp

Stilwell, B. (2021, March 16). 8 of the most terrifying Vietnam War booby traps. We Are the Mighty. https://www.wearethemighty.com/popular/8-of-terrifying-booby-traps/

The Creation of the Marine Corps’ Combined Action Platoons: A Study in Marine Corps Ingenuity. (n.d.). Www.usmcu.edu. Retrieved November 29, 2023, from https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/MCH/Marine-Corps-History-Winter-2018/The-Creation-of-the-Marine-Corps-Combined-Action-Platoons-A-Study-in-Marine-Corps-Ingenuity/

Wikipedia Contributors. (2023, October 25). I Corps (South Vietnam). Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Corps_%28South_Vietnam%29#/media/File:HCMC8.jpg