Mr. Charles Swann is a veteran who served in Vietnam in 1969. Mr. Swann volunteered to join the Marine Corps and trained at Paris Island. Later Mr. Swann joined the Combined Action Program that was designated to hold villages in Vietnam. Enlisting just as support for the war was beginning to dramatically decline, due to the Tet Offensive in 1968 and news of the My Lai Massacre and Operation menu in 1969, Mr. Swann chose to join the marines because of his family tradition of military service and sense of patriotism. Additional reasoning for Swann to undergo training with fellow Marine Corp volunteers was the buddy plan. The buddy plan allowed for friends who enlisted together to remain together for their basic training. Thus, the call for military service not only impacted Mr. Swann, but also his friends that volunteered alongside him. Had Swann waited a year, the chances of his being chosen by the Draft system would have been less likely due to the changes in the system in 1970. The draft which was originally based off age and birth order changed to a more randomized system.

Heading to War

The induction into the Vietnam War not only involved service with the possibility of life ending missions, but also included making personal sacrifices on the home front. For Mr. Swann that meant leaving his wife and newly firstborn son behind. Coinciding with a lack of communications to reach home, the jungles of Chu-Lai became solitary. Communication with the outside world relied on the occasional visits from a “Charlie Charlie Bird” which would bring rations, smokes, and a stars and stripes newspaper. Occasionally a letter from family would come and remind soldiers of the lives they have left behind. Trudging through the jungles outside of Chu-Lai the weather conditions and hygiene became hazards that bared down on American soldiers. The “heat and humidity” was described by Mr. Swann “like walking into a brick wall and I’m from Alabama so I should be used to that.” Along with the weather, injuries in addition to unfavorable conditions continued to demoralize troops in Vietnam.

Combined Action Program (CAP)

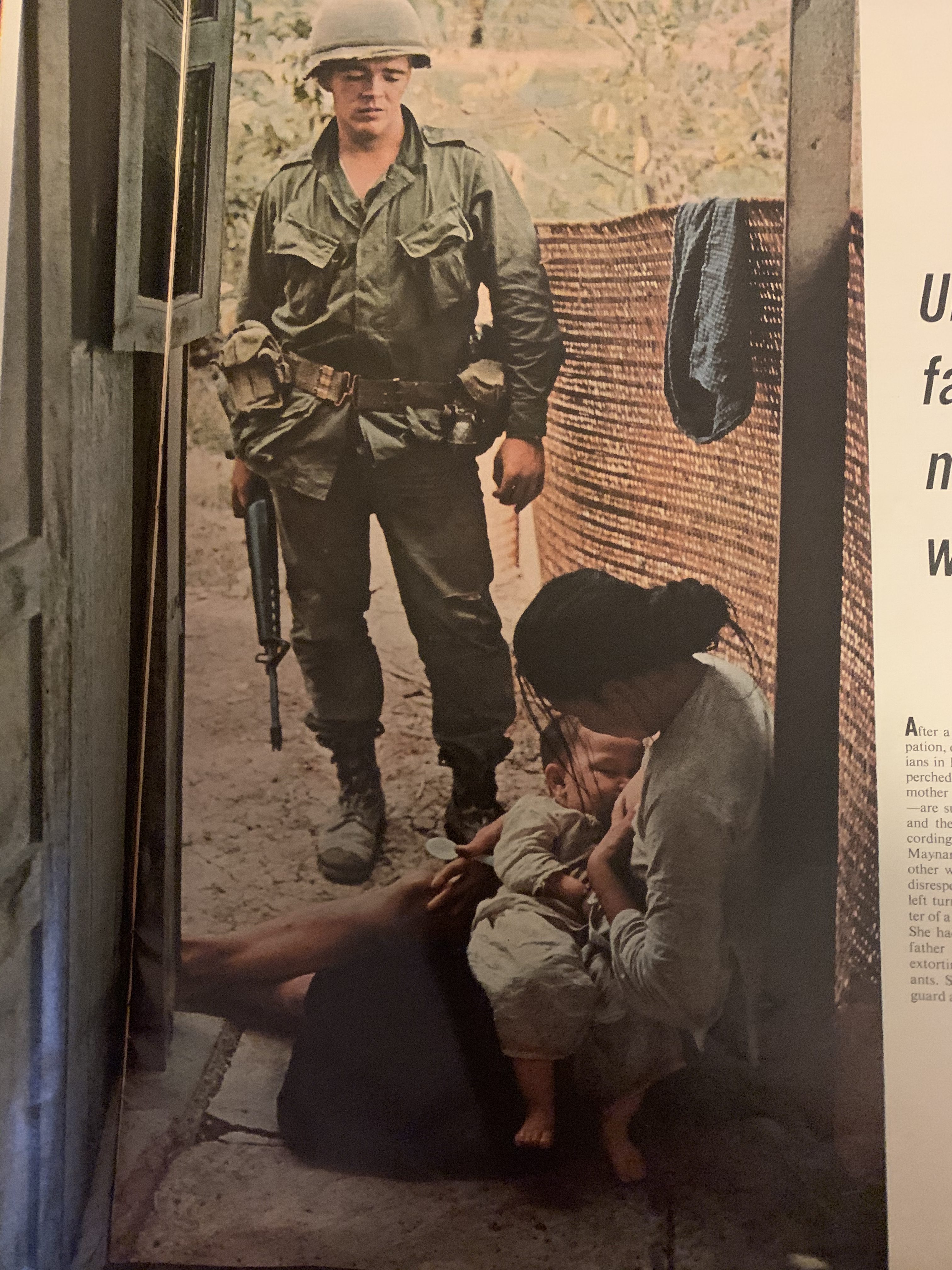

The Combined Action Program or CAP teams were designed to promote relations within villages and reduce sanctuary for the Viet Cong. The Program which started in 1965 helped to solidify control in more rural areas of Vietnam. While the primary focus of the program was to promote relations with rural Vietnamese, it also helped to impede the recruiting of villagers by the Viet Cong.

To join the Combined Action Program, Mr. Swann had to complete his basic training at Paris Island, deploy to Vietnam, and then be transferred to Da Nang where he will go to Combined Action Program classes. The learning portion of the program lasted around three to four weeks. Soldiers had to learn basic language and “taught you about what you would be doing so far as trying to train the local military, militia, and popular forces”. Once the schooling is completed, the soldiers were sent to their respective CAP teams. Mr. Swann was sent to the jungle outside of Chu-Lai where establishing patrols, recruiting Popular Forces, and fortifying villages became the daily life. Mr. Swann along with his CAP team also had the job of trying to root out any present Viet Cong that may have gone into the villages to seek sanctuary from American bombs that would be used during Operation Menu.

Propaganda and Recruitment

The fight against the Viet Cong progressively became a war of attrition and with it, the use of propaganda and other recruitment tools increased in value. Once Established, CAP teams were designated to continually enlist the help of the Popular Forces in the event of a Viet Cong attack. These Popular Forces recruits also accompanied American soldiers along patrols and defensive maintenance. One of the chief obstacles CAP teams faced when guarding villages and hamlets were the constant recruitment of the populace by the Viet Cong.

The Viet Cong resorted to tactics for recruitment that the United States prohibited. Often the Viet Cong was “resorting to ambushes and attacks on strategic hamlets to abduct men” (Donnell, John. (1967) :9). Among these infamous tactics used by the Viet Cong was their recruitment of children. The Viet Cong held large meetings that focused primarily on the recruitment of the Vietnamese youth. The focus on child recruitment indicates that the Viet Cong “would use any means they could, if that meant blowing up a kid they didn’t care”. This brutal tactic was meant to weaken the American soldiers both physically and mentally. In comparison, the CAP teams would focus on individuals who were draft age and older for assistance. Mr. Swann recalls working with the Popular Forces, stating that most “couldn’t have been older than 25” thereby establishing a generational divide in recruitment strategy.

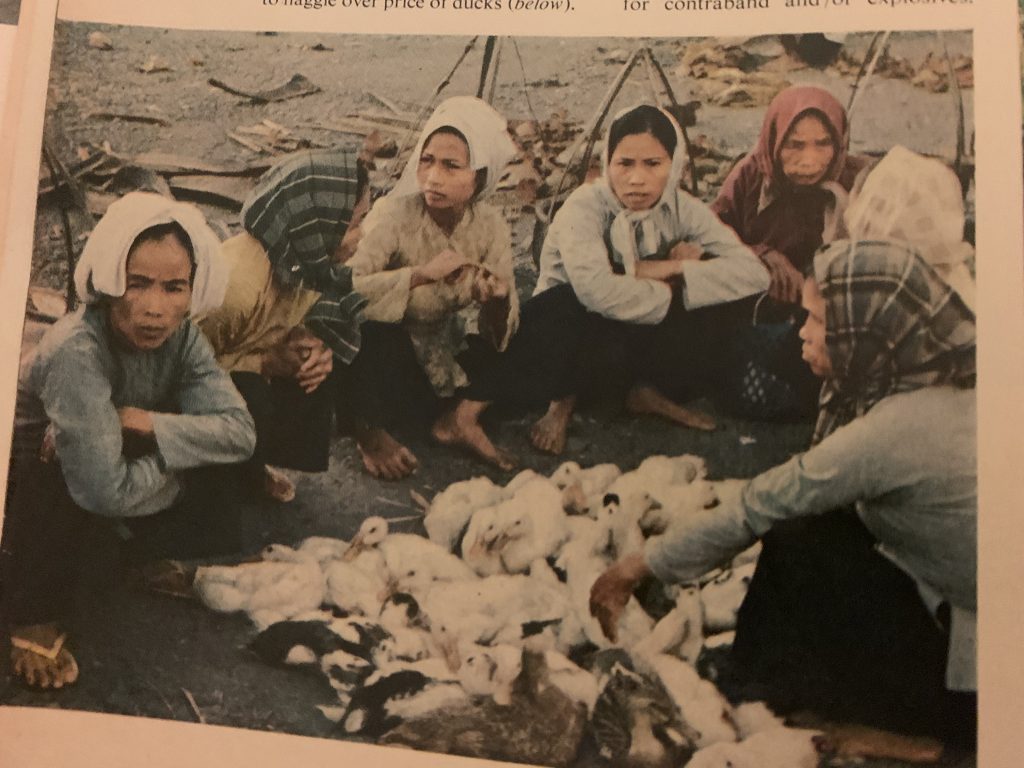

Rumors of the Viet Cong continually circulated throughout villages and would give CAP teams motive to attack or clear out the Viet Cong in their new strongholds. These rumors also led to Mr. Swann and his team to be ambushed when investigating a suspected village. In response to the increasing obstacles set by the Viet Cong, the CAP teams introduced the method of interchanging teams to provide continual support to each village. This constant stream of soldiers gave some economic promise for the inhabitants. As Mr. Swann recalls, women would leave the village and bring back Coca-Cola bottles to sell to the soldiers for 50 cents. Although trade became common practice, the villagers never fully accepted U.S. support. Mr. Swann’s impression was as though “they tolerated us. I don’t think they looked at us as their savior so to speak like they looked at soldiers in World War Two”.

Why Villages?

Although the villages were smaller than cities, they became immensely important for holding control of rural Vietnam. Considering the majority of the population could be found in rural communities, villages and hamlets were prime targets for recruitment. The Viet Cong and National Liberation Front focused primarily on areas not well defended by the United States or South Vietnamese Forces (ARVN) which usually resided in cities. While major cities were easier to defend, the rural communities became increasingly pressured by both the Viet Cong and the U.S. to align themselves with a side. In many cases the villages would be torn apart in their struggle to remain neutral. The losses inflicted on the Viet Cong led to higher demand for new recruits and in turn increased pressure used on villages to join the Viet Cong and National Liberation Front. Threats to the villages in rural Vietnam were never resolved and tactics used by the Viet Cong to attack the villages and its foreign defenders created constant instability within the villages. These attacks were mostly carried out with guerrilla tactics and traps that would be set by the Viet Cong. When the CAP teams held a village to support it from a possible attack, the Viet Cong would wait until nightfall to attack or set up traps that they knew “a damn American” would set off. The Viet Cong also had a major incentive for holding villages. Most of the villages showed potential for major agricultural production which the North Vietnamese government needed to feed its populace. The United States viewed the villages and hamlets as strategic holdings to diminish chances of rebellions and the expelling of Viet Cong. Both sides relied heavily on the villages they “liberated” and the result often led to bloodshed.

Home for good

Mr. Swann’s experience on leaving Vietnam is not considered ordinary in any way. While on emergency leave for his sister’s surgery and father’s recent heart attack, Mr. Swann reported to a reserve post in Alabama for thirty days. Just before he was to be sent back to Vietnam, the commanding officer informed him of the options he could take. The options included being sent back to Vietnam with a different CAP team or taking an honorable discharge. Mr. Swann, without hesitation, took the honorable discharge and never had to return to Vietnam. The aftermath of Vietnam continued to impede Mr. Swann’s life through nightmares and the public knowledge of how his fellow servicemen were demoralized in other parts of the country. Mr. Swann would later work in public service and retire in the city of Northport.

Audio and Transcript: Interview with Mr. Swann

Recommended Reads & Bibliography

–The Village. University of Wisconsin Press. 1985. West, Francis J.

–The Things they Carried: A work of Fiction. Houghton Mifflin. 1990 O’Brien, Tim.