Aug 4: Almost 5 months after the pandemic was declared a national emergency in the United States, 49% of low-income areas have no free beds in their intensive care units vs 3% of the wealthiest. Hospitals are now being forced to transfer their sickest patients to care facilities in these wealthier areas, with the Southwest and West facing an especially difficult bed shortage. A huge explosion kills at least 100 people near the port of the Lebanese capital Beirut. Missouri becomes the 6th red state to approve a Medicaid expansion for 230,000 of its low income residents. Trump urges Florida voters to mail in their ballots, even though he has been saying mail-in ballots are fraudulent for months. Trump signs a $3billion conservation bill for national parks and conservation projects. The Aurora, CO police chief apologizes for handcuffing and forcing four Black girls, one 6-years-old, to lay on hot concrete with guns pointed at them, last Sunday, because they suspected they had stolen a car.

Aug 5: Facebook removes a Trump post, saying it is spreading disinformation about the coronavirus. The clip said children were “almost immune.” from the virus.

Aug 6: New York Attorney General Letitia James announces she has filed a lawsuit alleging that the National Rifle Association is “fraught with fraud and abuse,” and is seeking “to dissolve the organization in entirety for years of self-dealing and illegal conduct.”

Aug 7: Stimulus checks from the first package rolled out seemingly quickly, but talks stall between the White House and Democrats on a potential subsequent round of relief, even as jobless claims reach a record high of 1.186 million. Trump continues to claim he will issue executive orders if a deal cannot be reached.

Aug 8: Paul Alexander criticizes CDC scientists for using CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports (“MMWRs”) to “hurt the President,” calling the scientific reports prepared by career CDC scientists “hit pieces,” and demands that he review each report before publication. Authorities declares a riot in Portland, Oregon, after a group of protesters set fire to a police union. Trump signs an executive ordered COVID relief bill amidst continued congressional stalemate.

Aug 9: US COVID cases surpass 5 million. Speaker of the House calls Trump executive order for a COVID relief bill, “absurdly unconstituional.”

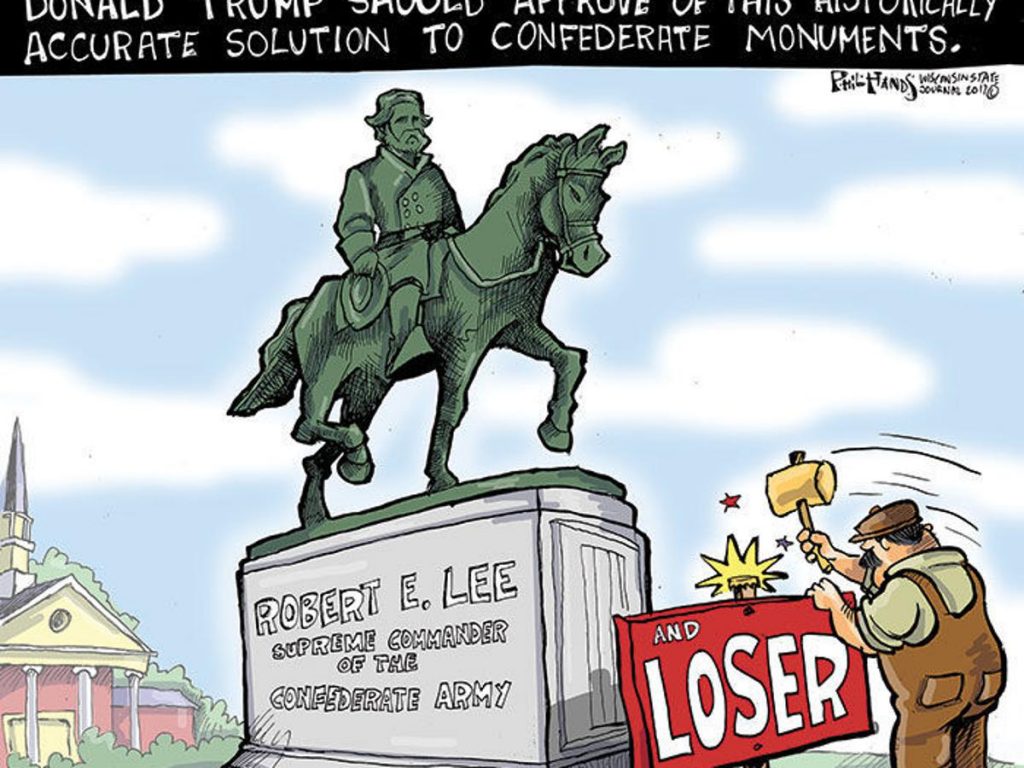

In response to the 2020 George Floyd murder amid a global COVID-19 pandemic, University of Alabama (UA) officials paid heed to the demands made by African American stakeholders and their diverse allies for a revised campus landscape defined by slavery, the Lost Cause and Jim Crow segregation. On June 8, 2020, UA removed three Memorial plaques and announced a UA system commission tasked with reconsidering problematic building names. The following day, more importantly, a facilities crew hoisted the 110-year old United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) Boulder off its pedestal and removed it from the centrally located Quad to an undisclosed location.[1] The home to the winning Crimson Tide football team became a footnote to the history of the COVID-19 pandemic. Between late May and July 31, 2020, 94 Confederate monuments have been removed by protestors or officials with another 74 problematic monuments removed, and 63 promised for removal and/or renaming across the United States and the world. Unlike these other monuments, the removal of the UDC Boulder from a greenspace where teams of enslaved people once hand cut the grass held personal significance.[2]

Since January 2015, I have been educating students, faculty and other campus stakeholders to reconsider persistent campus myths of slavery, its destruction, and its legacy. I have regularly incorporated the history of the monument in my classes. I had my students imagine a future campus where fuller narratives silenced by the landscape could be told and promote a more inclusive, diverse and equitable campus. After reading a chapter from Karen Cox’s Dixie’s Daughters and the student newspaper coverage of the dedication, my students and I analyzed the cultural artifact and brainstormed possible revisions.[3] While wanting to “blow it up,” students devised creative solutions but never thought that UA officials would actually remove it. Even the students who drafted the petition asking for its removal as part of their demands never expected administrators to remove it because they had ignored their pleas before. But, on June 9, 2020, they actually listened.[4]

What was this Confederate monument to the UA campus?

University officials accepted first of two Confederate monuments from the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in May 1914. Placed in the center of original Rotunda, the original monument rested on a small mound surrounded by a concrete border memorial financed by the Class of 1912. The dedication of the UDC Boulder attracted former Confederate veterans, including former Governor B. B. Comer, for a graduation ceremony held in Morgan Hall auditorium. Following these ceremonies, UDC women held a statewide convention. Like other Lost Cause symbols, the UDC Boulder featured prominently in yearbooks and daily campus activities.[5]

In 1939, UA moved the monument. Progress, and not student protest, prompted its relocation. The process resulted in a revised monument without its mound and original border.[6] During the mob violence resulting in the explosion of the first African American student, Ku Klux Klan members in full regalia and students waving Confederate battle flags received validation for their massive resistance against desegregation. It is not a coincidence that the grounds surrounding the UDC Boulder served as the staging area for the February 1956 rally. Its mere existence emboldened them.[7]

After campus desegregation, the UDC Boulder never elicited the same removal calls as it had at another SEC school. Mizzou students successfully relocated a similarly designed boulder from campus in the mid-1970s. Minor vandalism did occur as documented in the 1975 UA yearbook.[8]

By the time of my arrival in August 2014, the UDC Boulder had been naturalized in the landscape. Most did not see it. When tailgating before a Crimson Tide football game, revelers leaned against or placed their red-cup beverage atop it without reading its plaque. After the 2017 Charlottesville Unite the Rally events, I even had longtime staff ask me whether UA had any Confederate monuments. Most had not read the plaque on the UDC Boulder until I purposefully forced them to engage with it in a classroom setting or on an alternate campus tour. Like the various sites of slavery, the Lost Cause campus had been hidden in plain sight for most but sources of pain for largely students of color and black Alabamians who still refuse to step foot on campus.

After receiving the email announcement, I decided to get a few last photographs as I happened to be on campus. Instead, I captured the UDC Boulder sans its Lost Cause plaque with my cellphone. Students drafted the petition. Since previous demands had been met with promises and platitudes, I did not think that UA officials would act. In this COVID-19 pandemic, the speedy removal left me dumbstruck. I celebrated the moment of being present to witness the revised monument and then the freshly sodded grounds where the UDC Boulder once stood on the following day. Yet, doubt also crept in. Would a “we removed two markers and a monument, so we solved racism” culture emerge and stall future systemic change of revising other white supremacy? Would other student demands, such as African American faculty hires and scholarships, be ignored?

There are no easy answers to these questions. UA remains firmly connected to the broader history of Confederate monuments. The UDC Boulder and two plaques emerged during the first wave of the Confederate Monument craze. UA actively contributed to the Lost Cause commemorative landscape throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The 2020 removals are now linked to the Confederate Monument removal moment amid the COVID-19 pandemic. As an African American UA faculty member and a historian, I am grateful to be a part of this footnote to history.

Notes

[1] The University of Alabama System Board of Trustees, UA President Stuart Bell and Chancellor Finis St. John, “Joint statement regarding plaque removals at UA and formation of Building Names Review Committee,” June 8, 2020, University of Alabama System Office, Tuscaloosa, AL, https://uasystem.edu/news/2020/06/joint-statement-regarding-plaque-removals-at-ua-and-formation-of-building-names-review-committee/.

[2] Hilary Green, Monument Removals, 2015-2020, Google My Maps, Updated July 31, 2020, https://hgreen.people.ua.edu/csa-monument-mapping-project.html. All figures come from this mapping project.

[3] Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture, With a New Preface (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019), chapter 4.

[4] Stephanie Taylor, “University of Alabama removes Confederate monument,” Tuscaloosa News, June 9, 2020.

[5] Robert Oliver Mellown, The University of Alabama: A Guide to the Campus and Its History (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013), 41-43; “1912 Class Memorial,” The Crimson White, May 13, 1914, 1; “U.D.C. Monument to Be Dedicated in May,” The Crimson White, May 6, 1914, 1; “Honorary Degrees Given to Old Confederate Cadets,” The Crimson White, May 13, 1914, 1; “1912 Class Memorial,” The Crimson White, May 13, 1914, 1; Alabama Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy, Minutes of the Eighteenth Annual Convention. Alabama Division United Daughters of the Confederacy Held At Tuscaloosa, Alabama, May 13, 14, 15, 1914. Organized in Montgomery, April 30, 1897. Mrs. L. M. Bashinsky, President, Mrs. E. M. Trimble, Secretary (Opelika: Post Publishing Co., 1914), accessed in W. S. Hoole Special Collections; The Corolla, 1893-2014, W. S. Hoole Special Collections, Tuscaloosa, AL.

[6] Mellown, The University of Alabama, 41.

[7] B. J. Hollars, Opening the Doors: The Desegregation of the University of Alabama and the Fight for Civil Rights in Tuscaloosa (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013), 86-96.

[8] LeeAnn Whites, Gender Matters: Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Making of the New South (New York: Palgrave, 2005), chapter 6; Corolla 1975, v. 83, 108.

[/read_more

Hilary N. Green, “Confederate Monument Removal, 2015-2020: A Mapping Project,” Legend of Pin Colors: Confederate monuments (blue), promised removals, renaming, and lawsuits (yellow), global white supremacy examples (green) and other monuments (orange).

“Black Lives Matter protest gets heated in Gadsden, Alabama,” WVTM 13 News, August 8, 2020, https://youtu.be/FSCBM2QN-vw

Danielle Bainbridge, “Why are there SO many Confederate Monuments,” Origin of Everything, PBS Digital Media Studios, August 20, 2019, https://youtu.be/gSeht9CtM3s

“Explained: What happened in deadly Beirut explosion,” SkyNews, August 5, 2020, https://youtu.be/FnSr820S2Mk

“Beirut Explosion: A compilation of videos of the explosion and the aftermath,” Bilal Oz, August 5, 2020, https://youtu.be/yNH4eE3RYUM

*If the pdf thumbnails are not appearing, please reload the page.

You never see a confederate flag with a Biden flag pic.twitter.com/vaAsgPiflG

— Daniel Uhlfelder (@DWUhlfelderLaw) August 9, 2020

This page claims the Black militia NFAC will return to Stone Mountain on August 15th to fight white supremacists and burn a Confederate flag. But is it really an NFAC page, or a fake designed to rile up gullible Threepers? Spoiler: it’s a fake. pic.twitter.com/jZMHYOyIAZ

— F.L.O.W.E.R. (@flowerunited) August 9, 2020

This is insane.

— Mike Leslie (@MikeLeslieWFAA) August 5, 2020

A bride taking wedding photos as the explosion happens in Beirut.

And she’s one of the lucky ones, fortunate to survive.

(video by Mahmoud Nakib) pic.twitter.com/1zpE7YcB7M

BBC Arabic journalist Maryem Taoumi was conducting an interview when the explosion in Beirut took place

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) August 5, 2020

She was knocked over by the force of the blast but is safe

Warning: Contains upsetting scenes https://t.co/xdMWMBsOWJ pic.twitter.com/53dGzkXNEr

I’m so Over KANYE’s #Confederate Flag Trump loving shit🤬. So done. Not okay. Y’all still Wearing #Yeezy shoes & clothes After all this?!?! No pic.twitter.com/Smdl2pGH3k

— Daniel Newmaη (@DanielNewman) August 9, 2020

BLM protesters across the country are toppling statues of racist historical figures.

Elizabeth Warren led the fight on the political side, by managing to get all military assets named after Confederate leaders renamed. And she caused Trump to melt down. https://t.co/Y1vPVoexv7 — Amzi Qureshi (@AmziQureshi) August 9, 2020

White House reached out to South Dakota governor about adding President Trump to Mount Rushmore, New York Times reports https://t.co/0MqdAsJfft

— CNN (@CNN) August 9, 2020

CNN drone footage shows some of the devastation caused by the massive explosion in Beirut. The blast rocked the Lebanese capital on Tuesday evening, leaving at least 100 dead and thousands injured. pic.twitter.com/WEmFCQ7BSi

— CNN (@CNN) August 5, 2020

CLOSEST ACTUAL EXPLOSION FOOTAGE IN BEIRUT, LEBANON.

— kiki (@TweetReporterWW) August 5, 2020

To the person who took this video,

I hope ure still okay! #PrayForLebanon pic.twitter.com/zA67B0RhaT

Freshly out of quarantine and here photographing the addition of the rainbow crosswalk and the beginning of the dismantling of the Confederate monument pic.twitter.com/yNjpBErtPB

— Kathryn Skeean (@KathrynSkeean) August 9, 2020

“Stand up” for the guy who stands up for Confederate statues? Hard pass.

— Micah Joseph Hall (@micahh64) August 9, 2020

“It is a catastrophe, I’ve never seen something like that.”

— Al Jazeera English (@AJEnglish) August 5, 2020

Lebanon is in a state of emergency following a massive explosion in Beirut that killed at least 100 people and injured thousands.

Follow our LIVE coverage on the #BeirutBlast: https://t.co/8qEDq3qL5R pic.twitter.com/kSrpNt4oGf

* Timeline summaries at the top of the page come from a variety of sources:, including The American Journal of Managed Care COVID-19 Timeline (https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid19-developments-in-2020), the Just Security Group at the NYU School of Law (https://www.justsecurity.org/69650/timeline-of-the-coronavirus-pandemic-and-u-s-response/), the “10 Things,” daily entries from The Week (theweek.com), as well as a variety of newspapers and television programs.