Cataloging

Introductions

Earlier this summer, Rebecca invited me to join a Zoom meeting with Gesel and our team’s new archivist, Ellen Kamoe. She explained that they would be looking at the No Boundaries prototype, and specifically the catalog—trying to figure out if there were gaps that needed to be filled before publication. I hadn’t worked with the catalog yet, but Rebecca thought it could be a good point for me to join, and I was interested in seeing this part of the process, too.

But, before I get to this meeting, let’s go back: I joined the team in 2019. During this time, part of my role—at least in my mind—has been not just to participate, but to witness. To witness (and share) both the key and mundane in this process—the questions, uncertainties, drafts, learnings, breakthroughs, adjustments, blocks, answers, and new questions—as we have collaborated to increase access to the arts, support artists in sharing their work, and foreground and preserve the work of marginalized artists/scholars.

I am not a dancer, but I still find a place in the Dancing Digital/No Boundaries team. I am a qualitative methodologist, teacher, fiber artist, poet, jewelry-maker, and/and; I compose, choreograph, dance (Ulmer, 2023), across modes and genres, concepts and things. My work is often transdisciplinary and multimodal, drawing on embodied and creative knowings and practicings like fiber arts and poetry, while using feminist, critical and non-structural theories (Instagram: @course_of_inquiry).

Growing up, I spent a lot of time in libraries, so when I heard ‘catalog’ I thought of that – a database of records describing, identifying, and locating, a resource. I pictured Rebecca, Gesel and Ellen entering data into a spreadsheet that would then be uploaded into the archive. But, this has not been a ‘typical’ archive in a lot of ways. The team has emphasized stories and relationships, not objects; we have sought ways to open thinking and prompt questions rather than answer them—to invite curiosity, wandering. I wondered how a catalog participate in this goal.

I spend this time introducing myself because who I am matters for how I tell these stories, including this one on cataloging. I attended the meeting, curious to see what would happen. When they said ‘catalog’, did they mean a functional record of the entities located in the archive? If so, did it do what I thought—containing records describing, identifying and providing access points to, a resource? Did it do more?

Stories

As a qualitative methodologist, I believe there is no such thing as neutral knowledges or knowings. Accordingly, no entity (e.g., catalog entry) is objective, created from an omniscient point-of-view; this is the case for all aspects of the catalog. This is the case, for example, not only for the details—e.g., what a specific entry contains—but also for deciding what sort of information to include. (What counts as knowledge here? And whose knowledge is it? Who is it for? What will they want to do with this thing?)

It is tempting to look at a costume, describe what it is made of, record its measurements, label it with the performance name, and be finished. (Sometimes this is enough—sometimes it is all you have.) This is what I noticed that we did. Certainly, we asked ‘what is this?’, and answered technically, descriptively, observationally. (Checked for dates, names, locations.) But, we also asked…

…what are we cataloging…generally?

For Gesel, these aren’t just objects.

She holds up costume after costume; we observe through the screen, listening as she tells us how this or that choreographer was very specific about what she was to wear and how she was to wear it. That, she reminds us, is part of what she wants to share in No Boundaries. Not so much the specifics—that Kyle [Kyle Abraham] had her top designed for Don’t Explain, and they rejected or dyed multiple pieces to get it right; that her outfit in Rain is a new iteration modeled on Bebe’s [Bebe Miller], and that Bebe had very specific instructions for the parts; that the decision to take off part of her costume in the middle of Bent comes from a practice run in 2018 where she got overheated and took off a layer during a spin, and Jawole [Jawole Willa Jo Zollar] loved it—but what those specifics hold. The stories.

…who, and when, and where, are we cataloging?

Gesel holds up to the camera a sheer, black dress she wore for No Less Black. She conveys familiarity and annoyance: shows us the mended straps that she had to fix again and again, complains about the wrinkles the material always seemed to carry. She retrieves almost the costume’s twin, explains it was worn by another dancer, M K Abadoo in 2018 when she performed it in Brooklyn, NY. (She notes that it doesn’t wrinkle. She speculates about the material—rayon, perhaps.) She describes an earlier costume iteration, from 1999, a sheer, light blue dress. She directs us to an image of it. I think how interesting it is for a costume to be sheer. I wonder what it means to share, to wear, that type of transparency, that type of honesty, throughout time.

…how and why are we cataloging?

Material, runs through our conversation in unexpected ways—in ways that maybe don’t usually end up in a catalog entry, but seem important here. Gesel talks about how the materials looked on the stage, the shapes they made when she jumped, the ways the various components were fastened to stay on (or come off) during movement. We talk about associations and connotations, meanings and metaphors—intended and not. She describes aesthetics, practicalities and ethics, from the viewpoint of dancer, choreographer, curator.

The chain in David Roussève’s Jumping the Broom is of special interest in our conversation. In the solo, Gesel is chained at the ankles, tied at the wrist, and positioned in such a way, with her hands above her head, as to appear to be hanging from her wrists. She talks about how there is a very specific way she has to put it on so she doesn’t hurt herself, and how sometimes, if it’s too humid, the mechanism to undo it gets jammed. I notice how it seems to involve ‘others’ in a way different costume pieces don’t–practically and ethically. She has to be carried onto and off the stage while chained. She tells a story of her mom helping her attach the ropes on her wrist while she’s dressed in wedding dress that hides the chain, initially, from the audience. She expresses concern about how to catalog and share this costume, the dance, the history—she does not want to propagate images of Black women in chains—and, she knows that feeling the weight of the chains is essential, that these dances, her body, these costume pieces, are archives. She brings them to lectures sometimes, and we wonder (anew) about the central challenge of digital dance archiving: the conveying of embodied meaning and mattering across time and space and screens.

Closing Thoughts

First — Yes, a catalog is basically what I had anticipated. It definitely involves the recording of ‘accepted’ information – e.g., publication dates, call numbers. And, cataloging is also curating, storytelling, connecting. Like the choreography itself, the catalog depends upon all kinds of decisions—e.g., what to include, what to cut, how to present, what to link to. And, importantly, it is always done from the perspective of someone—artist, choreographer, archivist, or otherwise.

Second — This perspective is especially important for working with dance archives. After all, a catalog’s particulars and functionalities will (and should!) vary based on a number of factors. These include, for instance, the format and structure of the archive, the availability of information, financial and temporal resources, the purposes of the archive, and the nature of the entities being cataloged. As we have worked to create the No Boundaries archive, we have found that the last two—our purposes, and the nature of the entities in the archive—are especially important. Gesel, for instance, wants the collection to pull viewers in, to make them curious, by foregrounding the stories, the people, and the connections, that the many entities represent. In addition, cataloging dance already has unique challenges and possibilities because of, well, dance—its embodied nature, its histories and knowledges, the current status of the field (especially the availability of accessible resources), the (often) many parties involved in producing a dance, and/and. And that doesn’t even take into account that this collection highlights the work of Black artists—artists who, like so many others, have made and shared their art while dealing with legacies of misuse, appropriation, and erasure.

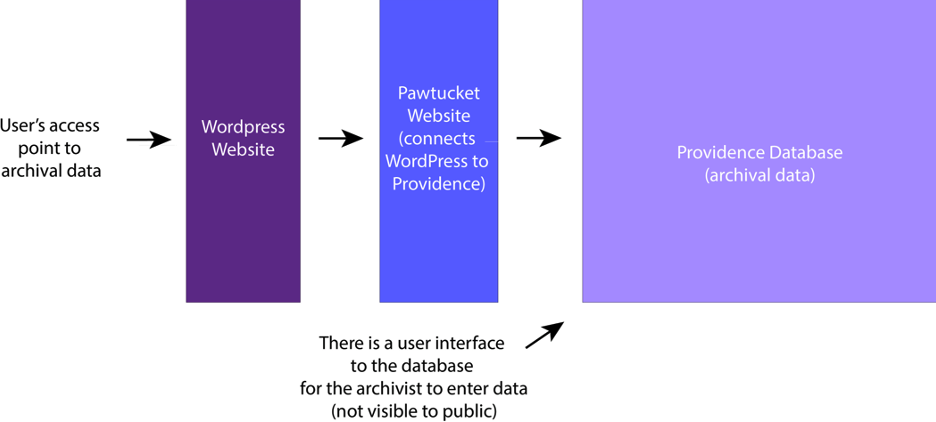

Third — Talking about and building a catalog almost necessarily involves talking about and building-with a lot of other pieces and parts in the archive. This is because an archive isn’t just made of pieces and parts, but pieces and parts that interconnect. Our conversation moved across a number of topics—permissions, back-end archiving maintenance, what kind of information should be included, who can access the catalog and for what purposes, goals for user interactions, and more. It’s all connected, and it all matters.

References

Ulmer, J. (2023). In the studio: Dance pedagogies as writing pedagogies. In D. L. Carlson, A. M. Vasquez, & A. Romero (Eds.), Writing and the articulation of postqualitative research (pp. 47-54). Routledge.